Less glamorous than jade, gold or silver ware, pottery gets less attention at museum exhibitions. Archaeologists, however, argue that pottery is the most important cultural relic for understanding human prehistory.

Unlike gold or jade, most ceramics are practical and designed for daily use. Pottery thus can offer a well-rounded view of the era it came from.

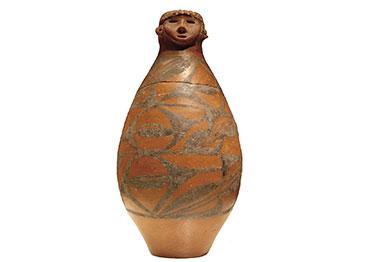

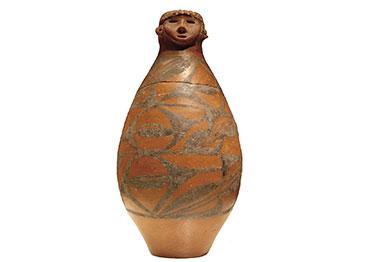

In the recent Palace Museum exhibition “The Making of Zhongguo – Origins, Developments and Achievements of Chinese Civilization,” a ceramic piece stood out – a painted vase with a human head sculpted at the rim.

The 31.8-centimeter-tall piece is made of red clay. The nose, eyes and mouth are hollowed out, and both ears have small perforations for earrings. These open facial orifices give the sculpture an expressive element.

The 1921 discovery of Yangshao Village, a Neolithic site in Henan Province excavated by Swedish scholar Johan Gunnar Andersson, marks the beginning of modern Chinese archaeology. The Yangshao culture is China’s first prehistoric archaeological culture characterized by painted ceramics that existed extensively along the middle reaches of the Yellow River.

Later archaeological discoveries and research extended the period and geographical scope of the Yangshao Culture. Dating back 5,000-7,000 years, experts consider it the most representative and influential Neolithic culture in northern China.

The vase was unearthed in Dadiwan, Northwest China’s Gansu Province. It dates back 5,500 years to the Miaodigou period, which scholars consider the middle period of Yangshao culture. Early Dadiwan culture had a matrilineal clan society.

The ceramic piece, the most important relic displayed at Gansu Provincial Museum, was discovered by a farmer. In 1973, Zhang Delu was tilling a field on the Loess Plateau, which has soft and loose soil, when he hit a hard object. Zhang picked it up and cleaned it off to find the unusually shaped ceramic piece.

After knocking off for the day, Zhang took it home. His wife, however, did not like it. She said it was a funerary object and did not want it in the house. So Zhang kept the bottle in their pigsty. A few days later, their pig died suddenly. Other villagers and Zhang’s family were quick to blame the vase. Zhang instead called a veterinarian, who said the pig had died of swine fever. Zhang’s family was appeased and let him keep the vase. He stored salt in it.

In 1978, a 5,000-year-old Neolithic site was discovered at nearby Dadiwan. Archaeologists conducting excavations heard about Zhang’s find. At first glance, experts identified it as a relic from Dadiwan and persuaded Zhang to give it to the museum for research. A month later, the experts rewarded him with two enamel washbasins on behalf of Gansu Provincial Archaeological Research Institute.

What is the origin story behind the relic? The China Central Television documentary series – The Nation’s Greatest Treasures – offers an interpretation.

Its dramatization focuses on a sister and brother (played by Chinese soccer star turned actor Wu Lei) of an ancient Yellow River tribe. The brother had traveled home from afar to find his sister deathly ill. When she asked him what to expect from death, he said she would soar into the sky and become a star. This eased her fears.

The brother took out the ceramic, which he made especially for his sister in her likeness, and handed it to her. It was his way of saying farewell. When the sister passed, her brother cut a wisp of her hair and put it in the bottle to store her soul.

Similar pottery offers insight into Yangshao funerary and spiritual rites, for example, the urn burial – which involves encasing a body in a large clay vessel.

In ancient China, the custom was mostly popular from the late Neolithic Age to the Han Dynasty (202 BC-220 AD). Up to the country’s founding in 1949, some ethnic minorities in southwest China practiced the custom.

Among the more than 80 urn burial sites in China, more than half belong to the Yangshao culture, as well as two-thirds of all urns unearthed in the country. The vast majority of Yangshao urns contained the remains of infants and children.

There are nearly 20 varieties of urns, including sharp-bottomed bottles, pots, tripods, jars and kettles. Yet they have a common feature – a wide round midsection, which experts believe was to provide a luxurious space for the soul.

A colored pottery vase with a human head is exhibited at Gansu Provincial Musuem, Lanzhou, Gansu Province, April 18, 2019

An urn coffin is displayed at Xuanhua Museum, Zhangjiakou, Hebei Province, April 29, 2012

Burial rites can reveal ancient people’s beliefs about the afterlife. For example, burial urns usually came in two parts that join in the middle. A distinguishing feature is one or more small holes were usually left in the top cover. At some archaeological sites, some urns were found to have their top rims deliberately broken off. Scholars believe this was intended to leave a way for the soul to come and go.

The head-shaped vase reveals many aspects of Yangshao concepts of creation and death. First, both have a wide midsection, which symbolizes pregnancy. Other examples of late Neolithic pottery of female figures found in Central Asia and Europe share fertility characteristics such as large breasts, wide hips and a long abdomen.

The painted pattern on the vase body is divided into three layers of roughly the same black design from top to bottom. The pattern is divided into two parts: one part comprises two arching triangular patterns that form a circle, which is filled with vertically arching patterns, while the other is composed of oblique and concave triangular lines. Though there is no definitive explanation as to their significance, experts believe that the patterns represent water and fish, which symbolize the cycle of life.

The patterns invite the imagination to connect it with other scenes of Yangshao life more than 5,000 years ago, as well as their ideas about life and their worship of motherhood.

The vase has captured the public’s imagination. In 2019, Yang Zhijie, a graduate student at Lanzhou University,created Fengwa, a cartoon character based on the 5,500-year-old vase.

Viewing this painted vase, one can feel instantly a distinct human connection that traverses thousands of years. The Yangshao culture’s concepts of death are yet another contribution to humanity’s search for life’s ultimate meaning.

Old Version

Old Version