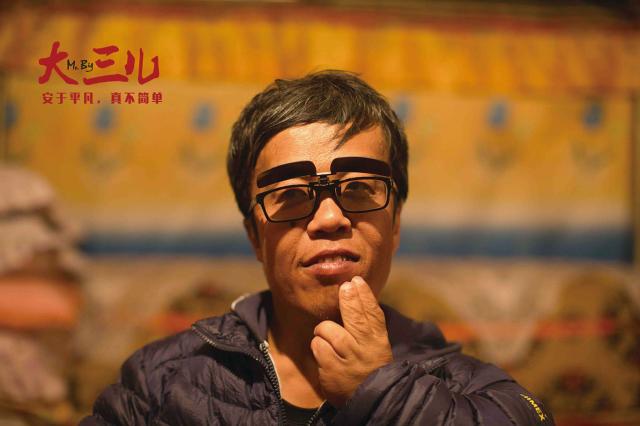

Ye Yun, nicknamed “Mr. Big,” is an average Chinese man. In his late 40s, he works as a cleaner in a copper factory in the city he grew up – Chifeng, 500 kilometers from Beijing in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. What makes him stand out is his physical difference – Ye, who has dwarfism, is 1.1meters tall.

He loves traveling and feels comfortable in places where no one pays him much attention. Three years ago he decided to go to the Tibet Autonomous Region – which might seem less risky for others but could be perilous for someone with his condition. Ye’s journey took him more than 5,000 kilometers from Inner Mongolia to the Potala Palace in Lhasa, then to the base camp of Mount Qomolangma, known as Everest in the West.

Ye never imagined his life would be the subject of a documentary feature. Now he finds himself the protagonist of a 106-minute film, Mr. Big, which documents his life in Inner Mongolia and journey to Tibet. The film was directed by Tong Shengjia, 35, a successful filmmaker who was once Ye’s neighbor. The film, which premiered on August 20, has been well received and deemed by critics as China’s first documentary feature centering on an everyday person.

Tong Shengjia has documented the lives of famous people for television, including the internationally acclaimed master painter Huang Yongyu and the renowned writer and translator Yang Jiang, who died in 2016.

Tong had originally wanted to make his first documentary feature about his former neighbor and childhood friend. But Ye saw it differently.

“What’s the point of filming my life?” Ye asked. Tong responded, “Sometimes ordinary can be extraordinary, not only on the screen, but also in his life.”

Ye is the youngest of three sons and a sister. His two older brothers were bus drivers, but they died in a car accident eight years ago. Their deaths were a huge blow to the family, and his mother died soon after the tragedy. Ye lives alone with his 84-year-old father, and the family is occasionally visited by his married sister.

Working in a copper factory earns him around 1,500 yuan (US$218) per month. His monthly expenditure is fixed: 300 yuan (US$43) for cigarettes, 200 yuan (US$29) on the lottery, 500 yuan (US$72) given to his father and 300 yuan kept as savings.

Every day he gets up at 5am, has a cigarette, and eats breakfast quickly. He is always the first to arrive at the factory and waits there for other disabled colleagues. His responsibility for the last decade has been cleaning the factory floors.

He gets off work at 5pm, and on his way home spends 10 yuan to buy five “double-color-balls” – a welfare lottery giant in China, all with the same number.

Ye dreams that one day he will win five million yuan (US$730,000) so he can give a speech about his win, which he has rehearsed for a long time. Outside the lottery station, he buys a packet of Hongtashan cigarettes in a grocery. Then he returns home and eats dinner with his father in front of the television.

In contrast with this simple life, Ye loves to travel – especially to big, crowded cities. Beijing is his favorite because the people in the bustling city don’t seem to pay him much attention. Missing are the curious stares of those from smaller towns who may not have seen someone with dwarfism before. Ye does not seek special attention or treatment. He feels uncomfortable when some people give their seats to him on a train or bus.

Says Tong: “He always surprises us by saying something seemingly simple but very thought-provoking and philosophical. Sometimes his words shed light on things you can’t figure out yourselves, as if he is standing in the terminal and looking back at you.”

Ye longs for love and marriage. In his early 20s he dated a woman with a disability, but the relationship broke down. He describes himself as being “greedy” because he says he wants a woman who is in good health. He sought help from a matchmaker, who told him owning a house was a prerequisite for marriage.

“I can’t have love or a family. Like it or not, it is the reality I have to face,” Ye tells Tong in the documentary.

The idea of going to Tibet occurred to Ye during filming. Day by day, it developed into a strong urge. He told his bold idea to Tong and their mutual friend Api, encouraging them to go with him.

Altitude sickness, unpredictable weather, potentially hazardous road conditions and trauma of his brothers’ deaths made it a difficult decision.

To prepare for his trip, Ye took out his savings, 4,000 yuan (US$582) in total, which he saved for years, and borrowed 6,000 yuan (US$874) from a friend. He did not dare to tell his father the truth, lying that he was headed to Sichuan to visit relatives.

He wrote a secret will the day before he departed, mentioning that this decision was his own choice, and had nothing to do with his friends. “Life has been predestined by Heaven. Whatever I might encounter during the journey, I take it gladly. After all, it’s taken all my effort to achieve it,” he wrote. He left the will and his bank cards with one of his workmates.

In June 2016 Ye hit the road and headed all the way to Southeastern China, along with Api and Tong’s film crew. The second half of the documentary recorded this expedition.

The road to Tibet proved difficult. Besides capricious weather – mist, showers and snow, they almost had a high-speed crash.

When they reach an altitude of 3,300 meters, Ye started to feel tightness in his chest and shortness of breath. For every 50 meters he walked he needed a 10-minute rest. When they reached 4,000 meters, a photographer in the team collapsed in the car, but insisted he could continue the job by using his telephoto lens to shoot them.

After the team arrived at the Potala Palace in Lhasa, Ye managed to climb all the steps to the top, 432 in total. Many Tibetans gave him a thumbs-up when seeing him strenuously climbing.

In front of the palace, Ye silently counted pilgrims’ long bows, as they prostrated themselves on the ground, moving forward slowly and following every step with a bow.

One man offered him a white, long khata – a ceremonial Tibetan scarf – and placed it around his neck. Tibetans give this greeting scarf to friends or guests as a welcome and a blessing. At first, Ye mistook the gesture for a hard sell and took the scarf off instantly; later, after finding out the meaning, he felt deeply grateful and ashamed of his initial suspicion of the Tibetan’s kind act.

During the journey, the team grew to understand Ye’s preference: He likes crowded places

much more than natural landscapes.

Many come to Tibet to see the awe-inspiring natural landscape and as a kind of purification of the soul. But Ye bore his workmates in mind wherever he went. He took pictures in order to show them what Tibet was like. He sent them postcards and bought them lots of souvenirs. He bargained in the Jokhang Temple, the most sacred temple in Tibet, and eventually bought a prayer wheel there at half price as a gift for Api.

“You are probably the first one to bargain in Jokhang Temple!” Api told him jokingly.

The most impressive scene is a midnight talk between Ye and the director at Qomolangma Base Camp.

On a starry night at the world’s highest peak, with Api snoring in the background, Tong asked Ye whether he felt his soul had been purified in Tibet, given so many people travel there for that purpose.

Ye’s response was: “Is my soul not pure? I think I have a very pure soul. Because I never hurt people.” After initially being amused, the director later found beauty and power in these words.

“I have seen menace in people, so I know the quality of ‘never hurting people’ is so rare and precious. There is so much unpleasantness we might encounter in life and every one of us may have a sharp knife in ourselves; but if we unsheathe the knife too often, we may also get ourselves hurt,” Tong told NewsChina.

He says the film is a “shield” for that “knife.” “When you feel miserable, you know there is one man called ‘Mr. Big’ who struggles with all his might to live in harsh conditions. Then you may think, if he can, why can’t we?” Tong added.

Ye’s tenacity also touched Pu Shu, one of China’s most popular singer-songwriters. “When people are tortured by misfortune, some completely break down. But he hasn’t. He responds rather positively to hardship. I like him because I can feel the light in him. It’s deeply touching,” the singer said.

The theme song of the documentary, “The Empty Sailboat,” is from Pu’s latest album Orion. The singer recorded a live version of the song for the production team to use for free.

Pu is not the only one moved by the film. Acclaimed Chinese screenwriter Zhang Ji regards the film as “a quintessential Chinese story” with “Chinese life wisdom in it” and says “It touches on various real problems that Chinese people face and also more fundamental problems concerning life, death and faith.”

China Film Archive director Sun Xianghui spoke highly of the film, saying: “The message on the poster – ‘I love each day in my life when I struggle with all my effort to live,’ strikes a chord with many of us. It not only tells Mr. Big’s story but presents the life of us all. The strenuous efforts that Mr. Big made to reach Qomolangma touched me and many viewers. We can see ourselves and hear our own voices in his life.”

“His charm, humor and philosophy unfold bit by bit in the film. Strong, optimistic, kind and passionate, such an interesting soul is hard to find. What has been deprived from you by life might be rewarded in other forms,” internet user “Happy Divide” commented on Douban, China’s biggest media review site.

When he came back to Chifeng, Ye wrote down his feelings about this special odyssey.

“Many came [to Tibet] much earlier than me, and many are still on the road. They usually have a very positive attitude toward life. I’m not the first one and won’t be last. I belong to one of them. I feel honored and grateful,” he wrote.

Today, Ye’s life has returned to its regular pace. He still buys five double-color balls every afternoon. He still has the hope of winning five million yuan and already has a plan for that money: He would buy an apartment to live in and another to rent out. Buying stocks or running a restaurant are of no interest to him. “I don’t have any business sense,” he says.

“I’m a bit greedy, am I not? Those desirable things that everyone seeks – love, friendship and a financially comfortable life – I hope I can get those as well,” Ye told NewsChina.

Old Version

Old Version