Since North Korean leader Kim Jong-un declared a policy shift in May 2017, announcing the country’s new focus is economic development, he has made some dramatic moves regarding its relationship with South Korea and the US. Following a landmark summit with South Korean leader Moon Jae-in in April, Kim met with US President Donald Trump on June 12 in Singapore. Pledging to work toward “complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula,” the summit initially led to hopes of a breakthrough in the decades-long hostility between the two sides

So far, there has been little progress between Pyongyang and Washington, with Trump on August 24 abruptly canceling a scheduled visit by US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to North Korea. While Trump complained there had not been sufficient progress, Pyongyang accused the US of “double dealing.” This leaves the two sides, once again, in stalemate.

With international sanctions still in place, a question hangs over whether North Korea’s new push for economic growth is sustainable. Will Pyongyang return to a path of confrontation if its diplomatic rapprochement with the US fails to lead to immediate benefits? NewsChina asked Zheng Jiyong, a professor and director of the Center for Korean Studies at Shanghai-based Fudan University, to share his insights on the prospects for Pyongyang’s policy shift to economic development. Zheng has visited North Korea many times, including a recent visit to Pyongyang in August, which focused on North Korea’s economic development.

NewsChina: Do you think the North Korean leadership is serious about its pledge that economic development and improving people’s livelihoods are its policy priorities?

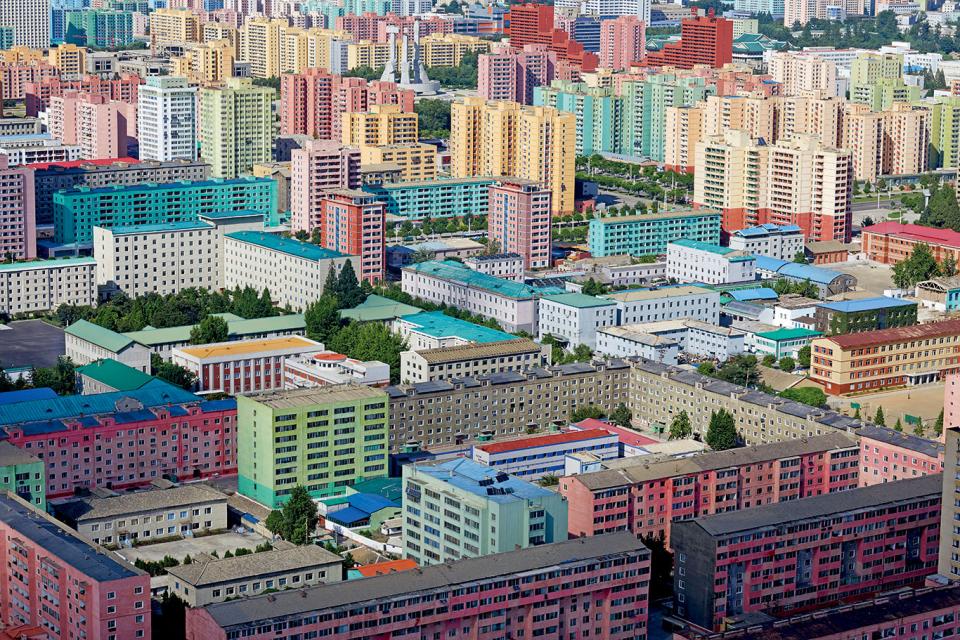

Zheng Jiyong: Yes, I believe so. In the past, North Korea has favored ‘monumental projects,’ such as Ryomyong Street [a showpiece urban development] in central Pyongyang, and power plants, which were mostly constructed in a campaign style with much political consideration behind them. Many of these projects are actually beyond the economic strength of the country.

After finishing these monumental projects which serve to embody the ‘greatness’ of its supreme leader, Pyongyang now needs to work to meet the needs of its people, or in North Korean rhetoric, to let people to feel the ‘kindness’ of its leader. Even Kim Jong-un said that ‘people’s livelihood is the biggest politics.’ On Pyongyang’s streets, many slogans which used to emphasize the need for military build-up have now been replaced with ones urging economic development. I believe North Korea’s policy commitment toward economic development is quite strong.

NC: Do you think there is a long-term plan behind North Korea’s new focus on its economy?

ZJ: During the 7th Congress of the Workers' Party of Korea, the ruling party of North Korea, held in May 2016, Kim proposed a five-year strategic plan for the country’s economic development between 2016 and 2020, covering a wide range of sectors. Addressing the country’s power shortages was its immediate focus.

NC: Was the plan based on the current international environment it faces or was it made on the assumption that international sanctions will be lifted?

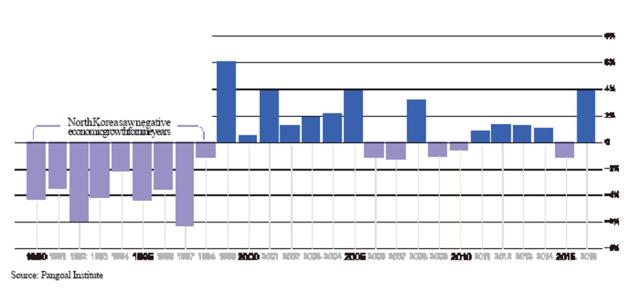

ZJ: I think North Korean leaders planned for both. After the meeting between Kim and South Korean leader Moon Jae-in in Panmunjom in April, Pyongyang had high hopes that some of the sanctions would be lifted. But as this has proved too optimistic, Pyongyang has resorted to autonomous development.

NC: Do you think this is the major driving force behind North Korea’s recent pledge to denuclearize?

ZJ: I think so. This is why it won’t be possible to have North Korea give up its nuclear weapons in the short term. Without a tit-for-tat scheme of mutual compromises, North Korea considering abandoning its nuclear programs would be a complete surrender to the US. North Korea expects to be rewarded for whatever it gives up at every step of the denuclearization process.

NC: Many have compared North Korea’s economic plan to the Vietnamese model. How would you categorize the North Korean approach?

ZJ: As the strict sanctions imposed by the United Nations are still in place, it’s too early to discuss which model North Korea will adopt. The security of the state remains the top priority for the North Korean leadership. We can say that North Korea is adjusting its policies, but its strategic focus remains on strengthening the country, which includes safeguarding the security and stability of the state, and then comes promoting economic development. For this reason, some have compared North Korea’s model to a mosquito net, which allows air in, but not ‘mosquitoes.’ I think North Korea would prefer to set up special economic zones – it did set up the Rason Special Economic Zone in 1992. But without a favorable international environment, this approach won’t get far. Given the uniqueness of North Korea, you can’t compare it to any other country.

NC: Since international sanctions will not be lifted soon, does that mean the significance of North Korea’s policy shift to economic development will not achieve much?

ZJ: Yes, this is exactly the situation Pyongyang has found itself in. Although North Korea has showed some goodwill, there is no sign that the US will lift the sanctions. On the contrary, the US appears to be expanding sanctions against Pyongyang.

If the sanctions aren’t lifted, North Korea’s econoic development will only proceed at a minimal level. But so far, North Korea has been trying to increase its cooperation with other countries in the areas least impacted by sanctions, such as tourism and cultural and sports exchanges. The tourist industry is considered to have the most potential. But even development of this sector has come under pressure from the US.

The question for the international community now is whether it should consider making a gesture to respond to North Korea’s goodwill. A major concern is that if North Korea sees no benefits for its perceived compromises, there will be no incentives for it to push forward the process of denuclearization.

NC: But for many, the concern is that once the sanctions are lifted and North Korea achieves some economic development, it could restart its nuclear programs. Is this a reasonable concern?

ZJ: The concern does have merit based on conventional wisdom, but personally, I don’t think North Korea will take that path, as it has become very clear to the North Korean leadership that if it does not change course regarding the nuclear issue, what it would gain, economically or politically, will be minimal.

Since he assumed power in 2012, Kim has taken a trial-and-error approach. In the past, he adopted a confrontational policy, conducting several rounds of nuclear tests and missile launches. This path has proven to be a dead end. North Korea’s recent rhetoric showed a notable shift in that it is striving to be considered a ‘normal’ country. It’s obvious Pyongyang is using the denuclearization issue as a bargaining chip to achieve its economic goals. This is also how North Korea intends to show that the country’s leadership can think and behave rationally and is capable of making deals with other countries – not only ordinary deals but also ambitious, bold deals. All in all, I think the process of denuclearization may take a long time, there may be major setbacks, but it is unlikely North Korea will return to the path of provocative confrontation through nuclear tests and missile launches.

Old Version

Old Version