Nima Jiangcai, the curator of the Yushu Museum, isn’t interested in exotic treasures or rare antiques. He wants the museum, and Yushu, in Qinghai Province, to be famous for the region’s own sake – because, he says, the area, the southeastern part of the Tibetan plateau, is one of the cradles of Tibetan civilization. The signs of this are in the very rocks themselves – or rather, the art painted on them.

Early rock art means human carvings on stone, found all over the world, and often characteristic of early civilization. Among the most famous examples are the prehistoric cave paintings in Spain and France, and the rock art of the Australian aboriginals. But Nima says there are examples – largely unknown to the outside world – all over Yushu.

His first findings came in 2007, when, with the help of a local, he spotted three carvings of deer on a rock by the bank of the upper reaches of the Yangtze River, known as the Tongtian River basin. However, three years later when he went back to the site, the original carvings have been replaced by new carvings of popular Tibetan Buddhist mantras. That discovery, and loss, started his own quest for rock art along the course of the river.

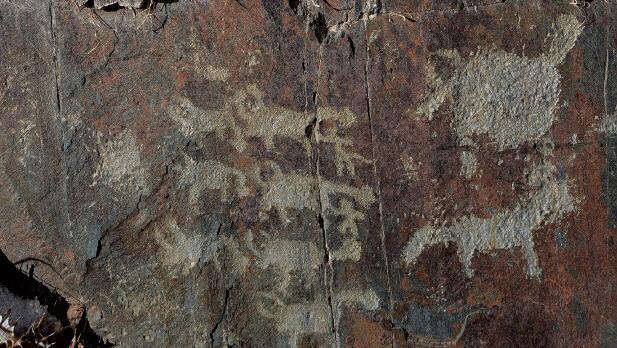

In the winter of 2012, in a secluded valley locals called Jorse on the southern bank of Tongtian River, he was thrilled to spot a total of 50 figures on a single piece of rock. They include humans, dogs, horses, leopards, yaks, deer, fish, foxes, wild cats and stacks of barley – and according to Nima, are clearly prehistoric. He named the style the “Jorse petroglyph.”

“The rock art in Jorse is mostly themed around hunting and farming, and the historical records indicate there was an abundance of wildlife and ample edible plants in the region. As an ideal environment with plentiful food, it’s not surprising we’ve discovered a whole range of rock art up there, varying in style, content, and scale,” Nima explained, noting that this indicated a long human history there. The wildlife depicted alongside human images suggests, according to him, the relatively harmonious coexistence of humans and nature.

Over the past five years, Nima and colleagues from the museum have recorded over 1,700 rock paintings along the upper stream of the Yangtze. In the next few years, he plans to focus on the upper stream regions of the Lancang (the Mekong).

Nima says that the style of the rock art conveys something of the time and place it came from. “The horns and rounded bottoms of the yak that we spotted on certain rocks are in a particular style, and quite similar to a lot of rock art from other civilizations such as prehistoric Central Asia. That could show that different cultural groups in larger regions were communicating with each other. Nima admitted that he hoped Yushu rock art could be an important element in connecting neighboring regions.

Professor Zhang Yasha, who works at the Rock Art Research Association of China at Minzu University, has researched the rock art in the Tibetan Autonomous Region for years, but is now shifting to study the art of Yushu as well. In an interview in Beijing, she mentioned that geographically, Yushu links Tibet and the rest of China, and its rock art is also a bridge between cultures. She believes that the cultural origins of the entire Tibetan-Qinghai Plateau may lie in the Zongri culture, dating to about 500 BC, found in archaeological excavations in eastern Qinghai.

“Many researchers have started to shift their focus from the Ali region in western Tibet to Yushu recently, and the role of rock art there is seeing a revival of study,” Zhang added.

Marginalization

Chinese rock art isn’t limited to Yushu. In northern China’s ethnic regions, for example, including Inner Mongolia, Ningxia and Xinjiang, tens of thousands of pieces of rock art, or traces of lost pieces, have been discovered.

Study of rock art inside China boomed in the 1970s, the same time as a rush of global interest in the topic. The remarkable rock art of Inner Mongolia was studied at that time by archaeologist Gai Shanlin. But after the 1990s, when archaeologists became frustrated by the impossibility of dating rock art, most Chinese researchers shifted their attention elsewhere, and the field became marginalized.

“Inside China, rock art is mostly found in ethnic minority regions, rather than the central China plain where the mainstream Han ethnic cultures dominate and the majority of the country’s cultural heritage originates,” Zhang Yasha told NewsChina: “As a result, rock art doesn’t get the attention other archaeological fields do.” In Central Asian countries such as Mongolia, Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan, Zhang says, the situation is very different, since what are minority cultures in China are the mainstream there.

It was in around 2010 that rock art began to experience a revival within Chinese academic circles. One of the biggest factors was the Guangxi government’s eventually successful pitch for securing the first World Heritage Site for rock art in China by 2016. About 1,800 images, believed to be created between the 5th century BC and the 2nd century AD, have been discovered on cliffs along more than 100 kilometers of the Zuojiang River in Guangxi Province. Covering an overall area of some 8,000 square meters, the Huashan rock art is the second largest area of rock art in the world, after the Nazca Lines in Peru. The World Heritage application gave a significant boost to government backing of rock art and its study. More and more young archeologists were drawn into the field, and now there are about 30 professional researchers focusing on the topic across China.

Mission

Nima Jiangcai plans to devote the rest of his life to rock art. He hopes to make Yushu Museum a digital museum for regional rock art in the near future, collecting all the information and images of rock art inside Yushu with detailed geological, historical and cultural explanations attached.

Nima says that it’s vital to deal with rock art now, since much of it is under threat from modern construction projects that have reached even the remotest mountains and gorges in Yushu. He’s been an active participant in international symposiums of rock art in recent years, hoping to learn from global researchers in the field and introduce Yushu’s rock art to others.

Zhang says that rock art is not a niche subject, but one not yet fully understood, and that much has yet to be learnt about its significance. “The study of Yushu’s rock art has a very hopeful future, and it can contribute substantively to the region’s history,” Zhang said.

The study on Yushu rock art is key to understanding the historical background of Tibetan culture and religion, but little serious research has yet been done. Like rock art elsewhere, most of the images are of wildlife and humans. Nima speculates that the interaction of humanity and nature on the plateau has a profound influence on local values. He praises the traditional Tibetan practice of sky burial, where corpses are left to decompose on the mountaintop and be eaten by wild birds, as one that returns the human body to nature. Other beliefs, such as respect for sacred mountains where humans can’t trample a single plant or slay a single animal, also indicate a sense of human subordination to nature.

The human-nature relationship is also a key part of the preservation of the Sanjiangyuan region’s particular ecology, the region where the Yellow, Yangtze and Mekong Rivers all originate. “How did human beings interpret nature, and how did they participate in natural processes? This heritage, passed down from our ancestors, has shaped Tibetans’ culture today,” Nima commented.“But if we fail to study and record this ancient rock art, we will soon lose it forever.”

Old Version

Old Version