For Chen, his movie The Stage tells a story of how “art transcends all” – a motto that features on the movie poster. “Art transcends all” is a principle held among traditional Peking Opera performers, meaning no matter what happens, the show must go on, and artists should put art above all else.

Written by distinguished playwright and Chen’s childhood friend Yu Yue, The Stage has been performed more than 330 times in 65 cities, including Vancouver and Toronto, Canada. The play scored audience ratings as high as 9/10 on China’s leading review website Douban.

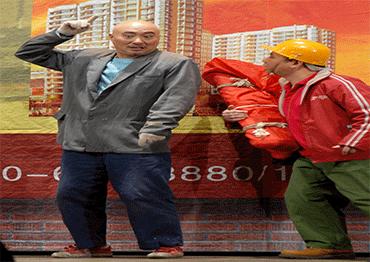

In the movie, Hou Xiting, played by Chen, is the leader of the famous Wuqing Troupe. The group travels to Beijing to perform classic opera Farewell, My Concubine, where they meet General Hong, a capricious and uncultured warlord who mistakes a waiter in a steamed bun restaurant for the troupe’s top star. General Hong threatens the troupe, forcing them to cast the waiter as the male lead, which leads to a series of calamities. Under huge pressure, the cast and crew are torn between their devotion to art and their fear of someone with power over them.

The conflict in the movie is a common predicament that affects artists throughout history: the arbitrary interference in art by those with power. General Hong forces the troupe to change the tragic ending of the ancient classic Farewell, My Concubine into a tawdry, happy ending. The warlord’s rude and overbearing demands give the artists no way out, making them determined to sacrifice their lives to defend the principle “art transcends all.”

In an interview with the People’s Daily in August, Chen explained his ethos. “People nowadays like to use the word ‘long-termism.’ In the past, older generations of artists used the expression ‘art transcends all.’ These two phrases deliver similar meanings. Generation after generation, artists in traditional opera troupes have stuck to this principle. They believe that a good show is a product practiced and polished for years. Artists must have such tenacity and persistence,” he said.

“Always respect our audience and never fool them. No matter how trends change, artists must stick to the rules and principles of art, no matter what,” Chen said.

The Stage movie has earned a high rating of 8/10 on Douban. Most viewers praised the work for boldly depicting artists’ persistence in defending the dignity of art in the face of a mighty power. “Political forces always change, but art remains constant. Classic art has an inner vitality that withstands time and war,” commented Douban user Li Meng. “Essentially, Chen Peisi uses a story set in the Republican period to satirize common phenomena, such as laymen guiding professionals, politics overriding art and institutions suppressing individuals,” another user Paradox commented.

“Either the narrative style or the comedy effects, The Stage is a typical ‘Chen Peisi-ish work,” said Huo Tang, a film critic based in Beijing. “Chen is particularly good at designing the plot around mix-ups, be it wrong locations or mistaken identities. The comedic effect comes from the dramatic irony they create – the audience knows what is happening, but the characters do not,” Huo told NewsChina.

In recent years, Chinese comedy films have heavily relied on jokes, wordplay and punchlines – “As if we are watching a standup comedy show or reading an audiobook of jokes” as Huo puts it. “But the thing is, audiences can easily enjoy funny skits in short videos or ultrashort dramas on Douyin. So why should they buy tickets and go to cinemas for a comedy film?” he said.

“The Stage, nevertheless, is a typical well-made play. The format features exquisitely designed plots, unexpected twists and tense theatrical conflicts. Creating such a well-structured, deliberately designed comedy is way harder and of higher quality than making a compilation of funny jokes,” he said.

Old Version

Old Version