He appointed the monk Tan Yao as “sramana general-in-chief,” the highest-ranking official in charge of all Buddhist and Daoist affairs. Tan Yao established formal institutions, secured stable economic support for temples and organized the large-scale translation of Buddhist scriptures. Most importantly, he initiated the excavation of the Yungang Grottoes.

Having personally witnessed the bloodshed and terror of the anti-Buddhist persecutions, Tan Yao constantly feared that such tragedies might one day return. Seeking to allow Buddhism to permanently take root in China and be spared from destruction by future emperors, he drew inspiration from the Indian and Central Asian practice of carving monumental grottoes.

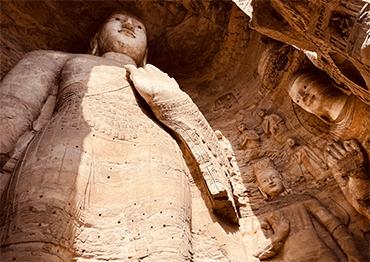

His idea was simple but powerful: if the Buddha statues were carved large enough to be grand and imposing, they would awe officials and the public, and would be physically difficult to destroy. Even if someone wished to erase them, it would take enormous effort.

But beyond size, Tan Yao had an even more ingenious idea. He proposed modeling each of the Buddha statues after the physical likenesses of the five emperors of Northern Wei up to that point, from the dynasty’s founder Tuoba Gui to the reigning Emperor Wencheng, Tuoba Jun. This way, the images would not only serve their religious purpose but also honor imperial ancestors, ensuring that future rulers would hesitate to destroy what were essentially portraits of their forefathers, even if they turned against Buddhism.

This plan won the full support and approval of Emperor Wencheng, and Tan Yao began excavating the first five caves of the Yungang Grottoes, now numbered Caves 16 to 20, each corresponding to one of the five emperors. Within two of them, he incorporated some especially thoughtful design elements.

Among the “Five Caves of Tan Yao,” the largest Buddha statue is that of the founding emperor, Daowu (Tuoba Gui). But what about the third emperor, Emperor Taiwu, who was infamous for persecuting Buddhists? Since he was the reigning emperor’s grandfather, leaving him out was not an option. So, Tan Yao came up with a clever solution: he dressed the statue in a heavy “Thousand-Buddha Robe,” adorned with over a thousand small Buddha heads, symbolizing the immense karmic debt Taiwu owed to the Buddhist community. The statue’s hands were posed in a gesture of repentance, and the weight of the robe represented the lasting burden he was to bear.

As for the fourth emperor, who was placed on the throne by the eunuch Zong Ai and quickly killed, Tan Yao made a significant adjustment. Instead of portraying this short-lived ruler, he replaced him with a statue of the late Crown Prince Tuoba Huang, Emperor Wencheng’s father.

After all, it was Tuoba Huang who had slowed the enforcement of Emperor Taiwu’s anti-Buddhist decree, saving countless monks and nuns, though at the cost of his own life. Still, since Tuoba Huang never officially became emperor, his statue was made slightly shorter than the others, subtly indicating that even a Buddha must compromise with worldly rules, and that even sanctity bends before imperial power.

Tan Yao’s approach, even by modern standards, proved remarkably effective. His “Five Caves” sparked a wave of Buddhist grotto carving throughout northern China.

Over the next century, the Yungang Grottoes expanded from the original five caves to 45 major caves and over 200 subsidiary niches. Buddhism flourished across China alongside this monumental artistry. With later reforms and the relocation of the capital from Pingcheng to Luoyang by Emperor Xiaowen (Tuoba Hong, 467-499, a grandson of Emperor Wencheng), Central China’s Henan Province, a new golden age began, marked by the grand, centuries-long excavation of the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang.

Today, both the Yungang and Longmen Grottoes are UNESCO World Cultural Heritage sites, admired around the world. And in the Five Caves of Tan Yao, the five great Buddhas, modeled on dynastic leaders who operated and witnessed the rise, fall and revival of Buddhism, still sit in solemn majesty, silently watching the tides of Chinese history.

Old Version

Old Version