Few Chinese consumers recycle their old cellphones over fears of putting the personal information they hold in someone else’s hands. Experts are now calling on the government to standardize and regulate the resale and recycling industry

A woman browses used phones at Aihuishou, a resale chain for used electronic products, Shanghai, September 26, 2022 (Photo by VCG)

While cleaning her Beijing apartment one weekend, Shi Qing stumbled upon five mobile phones she had long forgotten about. Among them was a Nokia handset she used over two decades ago.

Shi was unsure what to do with them. Reluctant to just toss them in the trash, the 39-year-old did not want to sell them either, as each phone held her personal information.

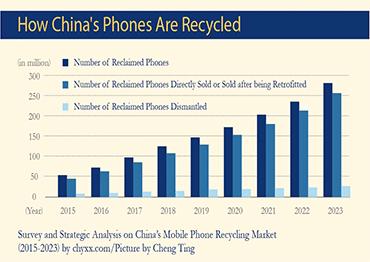

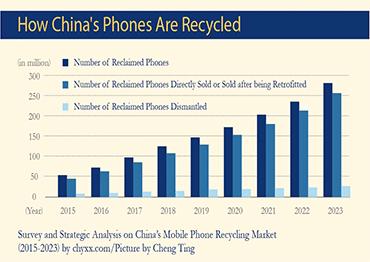

According to data from the China Association of Circular Economy (CACE), approximately 400 million unused mobile phones are discarded in China each year.

Used mobile phones are generally resold, salvaged for parts or destroyed to extract precious metals they contain like gold, silver, copper, cobalt and tungsten. However, the CACE reported that 54.2 percent of China’s unused phones are collecting dust on their owners’ shelves, with only 5 percent resold or recycled. Experts said that most consumers hold on to their outdated handsets due to fear of leaking personal information or out of dissatisfaction with resale prices. Furthermore, despite the expanding phone recycling market, unprofessional practices are rampant as industry standards lag behind.

Exchanging Numbers

In 2005, Nokia dominated the Chinese mobile phone market, accounting for nearly one-fourth of total sales. However, a survey of phone recycling in 13 countries by Nokia in 2008 showed that China recycled a mere 1 percent of its total unused phones.

“During that time, the resale and recycling market was largely occupied by private vendors… sparsely distributed and engaged in disorderly competition,” Chang Dalei, general secretary of the Chinese Resale Goods Trading Association, told NewsChina.

The turning point came in 2007 when Apple’s iPhone kicked off the smartphone era. The mounting popularity of iPhones in China supercharged the used phone market, as many iPhone owners upgraded every year.

The electronics markets of Huaqiangbei Street in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province soon became China’s biggest offline hub for sourcing used iPhones, which also extended to repairs, harvesting parts and refurbishing older models.

As new phone prices continued to rise, more manufacturers launched official trade-in services to help promote the sales of their new models.

“A second-hand phone creates about 20-30 percent profit from resale. Tradein services encourage customers to increase their budget on a new phone,” Wang Changwen who has worked as an instructor in the telecommunications industry for 10 years, told NewsChina.

Most companies have appraisal systems where prices are determined by how much a phone could be resold for, plus a 10 percent profit.

“When a customer learns that we will buy their old phone for 1,000 yuan (US$138), they might increase their budget for a new phone from 3,000 yuan (US$414) to 4,000 yuan (US$552),” a spokesperson for 9JI, the largest electronics retailer in southern Yunnan Province, told NewsChina. “That is why high-end phone consumers generally change models with the trade-in service,” he said.

In 2015, Apple released a batch of officially refurbished iPhone 6s on its online store. They sold out quickly. The next year, the company launched its trade-in service globally to encourage more customers to upgrade their phones. Chinese phone brands like Huawei and Xiaomi also launched similar schemes.

The phone resale market soon expanded to online platforms. Leading e-commerce platform JD.com, for example, launched its trade-in service in 2015. Today, they offer it in nearly 200 cities.

“We spent around 200 million yuan (US$27.6m) to promote our [trade-in] business in 2023, which helped double sales of new phone products,” a person in charge of JD’s consumer electronics division told NewsChina, revealing that JD plans to invest 3 billion yuan (US$414m) in the trade-in business this year.

Consumer Hang-ups

Despite these services, most people hold on to their old cellphones. According to a 2021 survey of 3,348 Chinese mobile phone users by environmental NGO the Society of Entrepreneurs and Ecology, nearly half kept their unused phones at home while 27.9 percent passed them on to relatives or friends. In addition, 24.6 percent of respondents said they had more than three unused phones.

Among those who keep their phones, 61 percent cited concerns regarding their personal information while 33.3 percent said they had no idea what to do with them.

“Mobile phones have become our biggest store of personal information – we even bind our bank accounts to our phones. How could I be at ease if these phones are in someone else’s hands?” Shi Qing told NewsChina.

Although most users know to do a full wipe and factory reset of their phones before selling them, experts warned that it is possible to restore deleted data. Media has reported on dealers selling recovered data in resold phones, from chat records and photos to contact lists.

“A key obstacle to the development of the phone resale market is the lack of phones... and that should be addressed by increasing consumer trust,” Guo Tianxiang, a senior analyst with IDC China, an IT and telecommunication industry consultancy, told NewsChina.

Dialing in Prices

Guo Zhanqiang, the general secretary of CACE, strongly encourages consumers to only deal with professional platforms or stores that follow strict processes to ensure the complete erasure of personal information. But many customers complain that specialized platforms and stores often lowball them, with some accusing vendors of artificially depressing the market.

Cao Gang, another Beijing resident, told NewsChina that he sold three old phones to individual buyers on Xianyu, China’s largest used marketplace app.

“I never thought of using professional [recycling] platforms, since a phone that could be sold for 3,000 yuan (US$414) on Xianyu only fetches half that or even lower on those platforms,” he said.

Many netizens commented on NewsChina’s official WeChat account that some platforms offer unreasonably low prices.

“Pricing a used phone is very complicated... Besides market trends, we also have to consider price changes in upstream and downstream industries and new phones of similar models,” Chen Xiaochen, strategic development director of Zhuanzhuan, a C2B2C sales platform for used electronics, told NewsChina.

“Mobile phones are not a standardized product and we appraise a used phone’s value based on quality checks,” she added. Zhuanzhuan follows 50-60 guidelines and over 100 detailed standards to appraise phones, Chen said.

According to phone reseller Tong Lei in Central China’s Henan Province, most resellers relied on experience and a sharp eye to appraise phones until 2017 when Aihuishou, another leading phone resale and recycling platform in China, released its six-tier appraisal system. Today, Aihuishou has 36 tiers ranging from cosmetic conditions to repair history.

“Prices gradually stabilized starting from that year, but those tiers are still not transparent enough, and individual resellers actually can decide the price themselves,” Tong said. As there is tremendous room to profit in resales, some unscrupulous sellers overprice refurbished phones or even pass them off as brand new.

On Sina China’s consumer watchdog website, NewsChina found more than 10,000 complaints about used mobile phone purchases, with many reporting discrepancies in the phone’s advertised quality.

Many who sold used phones to resale platforms said they knocked hundreds or even thousands of yuan off their appraisal prices, citing scratches, cracks and cosmetic flaws.

“Even though we have standards, appraisers differ greatly in their assessments... The entire industry is in its preliminary stages. Businesses have more autonomy now,” Chen said.

Unsmooth Operators

Aihuishou has been at the forefront of the emerging resale industry. Established in 2011 as a C2B platform, the company only received a trickle of old phones at first. To help increase volume, they opened physical stores in 2013.

By 2017, Aihuishou’s volume shot past 7 million units. They also launched additional businesses like online auctions. In June 2019, Aihuishou merged with JD’s used marketplace platform Paipai to provide a full range of services including B2B, B2C and C2C.

Despite the merger, Aihuishou incurred a net loss of 4.6 billion yuan (US$648 million) from 2018 to 2022. While there was a substantial decrease in losses in 2023, the company is not yet in the black.

Zhuanzhuan also shifted to used electronics in its 2020 merger with Tencent’s used phone marketplace Zhaoliangji. Chang Dalei considers the move a good sign for the industry’s future health and standardization.

At a brand strategy conference in Beijing in December 2022, Zhuanzhuan’s CEO Huang Wei said that Zhuanzhuan was no longer an e-commerce platform but a “circular economy company that values environmental protection.”

However, his claim did not help increase Zhuanzhuan’s sliding market value, as the phone resale market remains fiercely competitive and still lacks unified industry rules, experts said.

According to global industrial analyst Frost & Sullivan, China’s topfive enterprises engaged in used electronics occupy a 22.8 percent market share, indicating that the industry exhibits low levels of centralization.

“The whole industry is still in a preliminary phase,” Aihuishou’s president Wang Yongliang told NewsChina. “Over the past decade, our company has been exploring industrial rules and standards and trying hard to encourage users [to sell their old phones]. This takes money, and we made some detours before scaling up our operation,” he added.

People view an installation titled “Sleeping Treasure,” which includes 500 used phones, Beijing, March 30, 2019 (Photo by VCG)

Calls for Change

Phones not worth refurbishing are highly valued by recyclers, since every ton can yield about 200 grams of gold, 2,200 grams silver and 100 kilograms of copper, as well as other precious materials.

But recycling lacks industry standards as well. A significant amount of waste phones ends up in small workshops that contribute to severe pollution. In the town of Guiyu in Guangdong Province, thousands of households have been engaged in dismantling e-waste to extract their metals since the 1990s. These small-scale operations were generally unprofessional and damaged the local soil, water and air. The local government did not take action until 10 years ago.

Traditional extraction methods are rudimentary, require large amounts of fuel and produce harmful gases like carbon dioxide, said Du Huanzheng with the Ecology Civilization and Circular Economy Institute at Tongji University in Shanghai.

As a result, the extracted metals often contain high amounts of impurities. In a 2023 interview with Science and Technology Daily, Du pointed out that China’s current recycling and extraction technologies are inefficient and costly compared to those of developed countries.

As a professional e-waste recycler, AMM China under Singapore’s TES Envirocorp entered the Chinese market in 2005. Over the past decade, it recycled an average 1.5-2 million waste mobile phones every year. However, AMM China’s general manager Wang Yizhong told NewsChina that their capacity is far beyond the actual recycled volume. They simply need more waste phones.

Wang attributed this issue to China’s lack of a complete recycling system that extends from offline stores and platforms to communities and social organizations.

“The biggest challenge lies in increasing the awareness of waste phones’ value and their harm to the environment if they are not properly recycled,” he said.

“Environmental protection is the objective of the recycling industry, and if we can recycle all waste products in standardized and professional ways, it will produce economic interests and benefit the entire industry,” Wang added. “We can even resend the extracted metals to upstream suppliers to make new products. That is true recycling.”

Hong Yong, an expert from the China Digital and Real Economy Integration Forum 50, suggested that the government guide the establishment of a recycling system, unify standards and operations, and raise public trust in professional recyclers. He believes that such a system would fill the market gap, especially in rural and remote areas.

In March, the State Council, China’s cabinet, unveiled a plan to promote trade-ins of old consumer goods in an effort to boost consumption. The plan includes financial and policy support for e-waste recycling, as well as resale and recycling standards for used phones, including the protection of personal information.

“The government support is expected to direct more used phones to flow to professional and standardized resale and recycling platforms, which will be the starting point of positive development,” Guo Zhanqiang said. “It means that the threshold of entering the industry will increase and phone recycling will no longer be a simple business that anybody can do with a screwdriver,” he added.

Old Version

Old Version