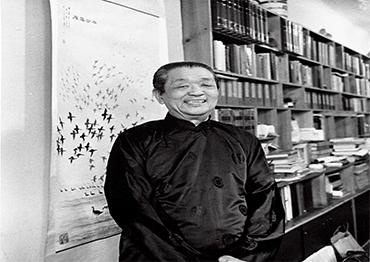

Wearing his black Chinese-style gown, Chiang stood out among the other speakers at Harvard University’s Sanders Theater as he delivered his speech for academic honor society Phi Beta Kappa on June 11, 1956.

Themed “The Interdependence of All Cultures,” Chiang’s speech emphasized the importance of mutual understanding among peoples, highlighting the need for global harmony.

Chiang was the second Asian to deliver a speech for the prestigious society, following the renowned Bengali philosopher and poet Rabindranath Tagore. This recognition from the American academic community reflects the significant impact of Chiang’s work. He was subsequently appointed as Harvard’s Emerson Fellow in Poetry.

Chiang went on to teach classes on Chinese culture at Columbia University in New York, all the while continuing to write his Silent Traveller series.

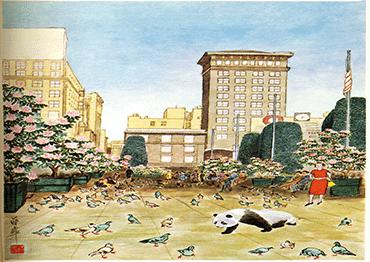

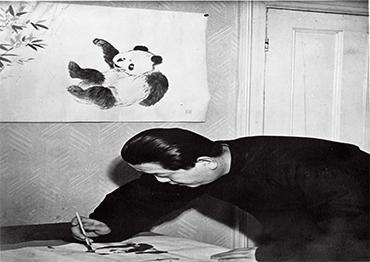

Published in 1964, his San Francisco travelogue features a serene painting of a panda ambling leisurely among dozens of pigeons against a colorful backdrop of flowers, pedestrians and tall office buildings. He called it “An Oriental in Union Square,” using it as a metaphor for his own identity.

Zheng Da notes in the book that no matter how Chiang’s status changed, he was still a “panda man” – an observer in a foreign land.

As diplomatic ties between the US and China improved in the 1970s, Chiang saw a chance to return to China. In April 1975, after 40 years abroad, Chiang reunited with his wife Zeng Yun and his children in Nanchang, capital of Jiangxi Province. There he met his grandchildren for the first time.

He had mixed emotions about the return: “All the time I sat there looking at everyone, I had acute pain inside me, yet I could not show it in my face, for this reunion of us all was a miracle such as I had never dreamed of,” Chiang wrote in his book China Revisited.

During his two-month visit in China, Chiang visited over 20 cities. Upon his return to the US, he documented his experiences and wanted to make his life story known to the world. According to Zheng Da, he became more outspoken and unrestrained, a significant change in Chiang’s demeanor.

For the first time, he openly discussed his political past in China and his disappointment with Chiang Kaishek, the head of the Nationalist government (1928-49). He also expressed his admiration for Mao Zedong, the founding chairman of the People’s Republic of China. “This dramatic transformation revealed him as a new being that was cloaked patiently and quietly in disguise over the previous four decades,” Zheng wrote.

Chiang’s love for his homeland remained unwavering until his passing. In August 1977, he made his second visit to China, which was filled with traveling to historic sites, visiting with relatives and friends, and going to Peking Opera performances. However, the demanding schedule triggered a relapse of colon cancer, which he was diagnosed with only two years earlier.

Intending to return to the US to continue teaching at Columbia University, Chiang had ended his travels with a final journey home. He ultimately passed away in Beijing in late October 1977. Chiang was 74.

Interestingly, he shared a similar destiny with his old friend Shi-I Hsiung, who also passed away in Beijing during his own return to China years later.

In a eulogy delivered during the memorial service held at Columbia University, William Theodore de Bary, the school’s executive vice president, described Chiang as “the embodiment of the Chinese scholar, poet and painter who made China live in New York and grafted something of himself onto our common life at the university.”

De Bary continued: “Our sorrow is lightened by the thoughts that our departed colleague has only departed in the way the ‘silent traveler’ often did, and that he will still be going and coming in our lives.”

Chiang was laid to rest at the foot of Mount Lushan in his hometown of Jiujiang, alongside his brother, Chiang Ji, and his wife, Zeng Yun. Through the unique perspectives in his work, Chiang embodies the cultural openness and shared curiosity that help to bring the world closer together.

Old Version

Old Version