At one time, archaeology was not a place for outsiders. But in recent years, it has captured the public imagination in China with movie blockbusters about tomb raiding like The Lost Tomb and the mysterious new findings at the Sanxingdui excavations near Chengdu in Southwest China. There is even a popular toy set that lets children imagine they are an archaeologist through play.

This includes mystery boxes, with a small “terracotta warrior” buried in dirt inside. You have to uncover and clean it with the toy tools provided to discover what kind of warrior is inside. It could be a standing or a kneeling warrior, or even an emperor. The experience of expecting something unknown is quite a thrill.

While modern archaeological techniques were imported from the West, China has its own tradition of studying antiquity. Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072), numbered among the eight greatest writers of the Tang and Song dynasties, wrote a book about his studies of inscriptions on ancient bronze and stone pieces. He pioneered jinshixue, or “metal and stone studies,” which focuses on studying and interpreting inscriptions on ancient metal or stone objects. This would later be known in the West as epigraphy.

Archaeology involving excavation, scientific research and modern techniques started in the West only 150 years ago, and was brought to China some 100 years ago.

In 1873, German-American Heinrich Schliemann believed he realized his childhood dream of proving that the city of Troy described in Homer’s epic poetry was real. He and his team of 120 discovered what he called Priam’s Treasures, a cache of gold and precious objects. He named it after the last king of Troy, after three years of excavations at the site in present-day Hissarlik, Turkey. He continued to organize and sponsor excavations of seven ancient Greek sites, including those of the Mycenaeans, a late-Bronze Age civilization centered in the Peloponnese. But his excavation of ancient Troy shook the archaeological world. It revealed nine levels of occupation, one built on top of the other. The layer containing Priam’s Treasures was from a city about 1,000 years older than Homeric Troy. Recognized as a pioneer in the field, Schliemann was also a successful businessman, which funded his adventures in archaeology.

In China, archaeology was also the shared dream and passion of a businessman and a group of scholars, a dream that was fed by Western-led expeditions in China.

In 1857, one year before 36-year-old Schliemann began his excavations, Liu E was born in today’s Zhenjiang, Jiangsu Province. His father was a Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) official.

Liu grew up to become a renaissance man. He was an entrepreneur, novelist, diplomat, musician, practitioner of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), hydraulics expert and epigrapher.

But Liu is best known for his satirical novel that takes on the seedy underbelly of Qing governance, the rise of the Boxers and the failing Yellow River flood control system. The book has two English translations: Mr Decadent (1947) by well-known Chinese translator Yang Xianyi and The Travels of Lao Can (1952) by Harold Shadick, a professor of Chinese literature at Cornell University.

Hu Shi, a prestigious scholar of the early 20th century, praised Liu’s two greatest contributions – flood control projects on the Yellow River and his pioneering work with early Chinese scripts, as setting the stage for China’s first archaeological excavations.

But Liu had his share of professional failures. His early businesses, which included a tobacco shop, TCM clinic and publishing house, all flopped. He failed the imperial examinations and lost his chance at a government career. Instead, he served as an advisor to the governors of today’s Henan and Shandong provinces, which are in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River. Like his father, Liu was a hydraulics expert. He helped design flood control projects along the Yellow River, and later worked in the Zongli Yamen, the Qing government’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In 1897, a British-Italian company called Pekin Syndicate Limited was incorporated in London. Its purpose was to invest in coal mining and railways in China. The Rothschild family was its main investor. Italian businessman Angelo Luzzati was the company’s first representative in China. As foreign investment was not allowed in China’s mining sector, it was instead operated by a Chinese shell company run by Liu. This business brought Liu a fortune, making it possible for him to collect antiques, including thousands of oracle bone inscriptions.

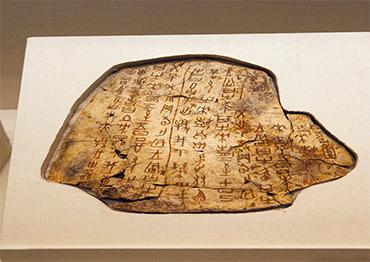

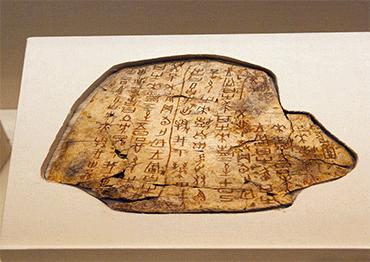

Oracle bones were discovered by accident. In 1899, Wang Yirong, principal of the Guozijian, the Qing Dynasty Imperial College in Beijing, noticed strange inscriptions on animal bones and turtle shells sold for use in TCM. At the time they were called “dragon bones,” a colloquial name given after farmers working near Anyang, Henan Province discovered piles of them in pits. He bought about 1,500 of the bones from TCM sellers to discover whether they were an ancient Chinese language.

However, the next year, a force of eight Western powers invaded Beijing. Wang committed suicide with his wife and daughter-in-law. In ancient times many scholars and officials and their families committed suicide to show loyalty when their dynasty collapsed due to invasions or rebellions. His son then sold the bones to Liu.

Liu collected more. He eventually amassed more than 5,000 pieces. After close study, he concluded they bore the ancient script of the little-known Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE), which ruled 3,000 years ago in the present-day city of Anyang, a former Shang capital where the “dragon bones” were found.

In 1903, Liu published the results of his research on what we know today as the oracle bones. He asserted that the inscriptions, mostly found on ox bones and turtle shells, were used in divination rites. They remain the earliest examples of Chinese script.

Liu’s work inspired four scholars to spearhead research into ancient Chinese languages. Two of them, Luo Zhenyu and Wang Guowei, were related to Liu through marriage. Their research made it possible for another two scholars, Guo Moruo and Dong Zuobin, to make breakthroughs in deciphering the ancient characters and in archaeological excavations.

In 1928, Dong Zuobin led a team to start excavating the ruins of the Shang capital in Anyang. Sponsored by the ruling Kuomintang government, it was the first time an archaeological excavation was independently organized and conducted by China in modern times. In the years since then, 15 excavations were conducted at the site by pioneering Chinese archaeologists such as Li Ji (known as Li Chi as a staff member of the US’s Freer Gallery of Art from 1925 to 1930), a Harvard graduate and the first Chinese with a PhD in anthropology, and Liang Siyong, another Harvard graduate of anthropology and archaeology and the second son of the prestigious scholar Liang Qichao. Previously, only written records on the Shang Dynasty were known to exist. The unearthed ruins of a palace in Anyang provided visible and solid evidence of the Bronze Age civilization.

However, the Kuomintang had a shaky hold on power, and archaeological excavations were not a priority. But Chinese scholars could not wait any longer, as Western adventurers and scientists had been conducting them in China for a long time.

In 1900, the year Wang Yirong committed suicide, Swedish explorer Sven Hedin discovered ruins of the ancient Loulan Kingdom at the edge of the Lop Desert in what is now Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The same year, Chinese Taoist Wang Yuanlu found a cave containing huge amounts of ancient manuscripts and documents, mainly about Buddhism, in the Mogao Grottoes complex near Dunhuang in northwestern China’s Gansu Province.

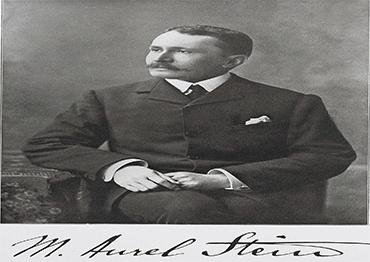

In the following years, foreign explorers from Britain, France, Japan and Russia bought, robbed and smuggled most of the books in Mogao’s “library cave” out of China. For example, Marc Aurel Stein, a British-Hungarian archaeologist took more than 10,000 Dunhuang texts in his 1907 expedition, later kept in the British Museum in London. French Sinologist Paul Pelliot took another 5,000 items in 1908 which were housed in the Louvre in Paris. When Pelliot arrived in Beijing on his way back to Paris, Luo Zhenyu and Wang Guowei, two of the four leading Chinese scholars on oracle bone inscriptions, visited him. Luo took photos of some of the Dunhuang documents taken by Pelliot, who said that there were still about 8,000 manuscripts in the Dunhuang caves.

Luo called on the Qing government to protect the remaining documents and devote more resources to the study of ancient languages and texts. But the Qing was on the brink of collapse. In 1911, Luo Zhengyu and Wang Guowei moved to Japan after the fall of the Qing and China’s imperial system that year. It was there that they focused on researching the oracle bone inscriptions and Dunhuang documents based on the photos of Pelliot’s collections.

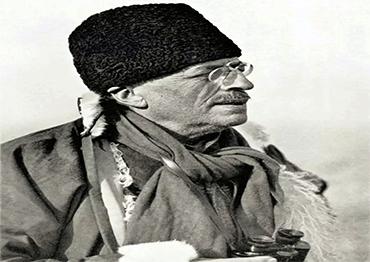

Sven Hedin returned to China in 1927. His plan was to lead an international team of archaeologists, biologists, meteorologists and historians to conduct a large-scale survey in China’s northwest. At the time, foreign expeditions in China did not have to get official permission. But there was growing awareness of national sovereignty among Chinese elites. This time, Chinese scholars protested. They then reached an agreement. Chinese scholars would join Hedin’s expedition and all discovered antiques and documents would belong to China.

The foreign-led archaeological expeditions eventually inspired Chinese scholars to conduct research in the country independently. Anyang is regarded as one of the two birthplaces of modern archaeology in China. The other is Yangshao Village, also in Henan Province, where China’s first Neolithic culture was found in an archaeological discovery led by Swedish geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson with his Chinese colleagues in 1921.

In Anyang, China’s archaeological efforts have continued since 1928. One of the most significant findings was the tomb of Fu Hao discovered in 1976, the first ancient tomb to be found intact at the site. Fu Hao, a royal consort and military leader, was found buried in a looted tomb with hundreds of precious burial objects, making her the first person in Chinese history whose existence was confirmed by an archaeological discovery.

Fu Hao was one of the more than 60 wives of Shang King Wuding who ruled around 3,300 years ago. She was a very brave general and won many battles, including one in which she led an army of 13,000 soldiers to fight neighboring tribes, a very large army for the times. Fu Hao also presided over many worship ceremonies. Shang people worshiped nearly everything, including nature, their ancestors and heavenly gods. Fu Hao helped her husband bring the dynasty to its height.

The most recent major discovery in Anyang in 2022 includes sites dating back to the Paleolithic Age and new functioning areas of the Shang capital. In Yangshao, more Neolithic relics were unearthed in recent years.

Old Version

Old Version