In 1565, Li put on his straw shoes, threw his medical bag over his shoulder and traveled far and wide into the mountains and wilderness, visiting well-known doctors and scholars in search of folk remedies. He observed their methods and collected specimens, accompanied by his apprentice Pang Xian and his son Li Jianyuan. They covered what are today’s provinces of Hunan, Jiangxi, Anhui and Jiangsu, and many other places.

Everywhere Li went, he talked with herb pickers, farmers, fisherfolk, woodcutters and hunters, all of whom helped Li understand various medicines. For example, yun moss was a term commonly used in prescriptions. Although described in many medical books, it was not precisely identified. But under the guidance of an elderly man who grew vegetables, Li learned that yun moss is nothing more than oilseed rape.

During these decades, a Taoist temple in the Wudang Mountains abounded in a certain kind of plum. The Taoist priests there believed that by eating the fruit, one could become immortal, so they picked the plums every year for the emperor and banned others from picking them. Skeptical of the claim, Li stole one. He found it had the same efficacy as other ordinary fruits such as peaches and apricots.

Another ingredient commonly used in TCM was the scales of the pangolin, now a highly endangered species. A medical practitioner in the 6th century described the pangolin as an amphibious creature that climbs onto rocks during the day, spreads its scales and pretends to be dead to lure ants under them. Then it traps them underneath, dives into the water and spreads its scales again so the ants float to the surface. Then it devours them.

With the help of woodcutters and hunters, Li caught a pangolin and removed about one kilogram of ants from its stomach, confirming that pangolins eat ants. However, he found what we all know to be true today – pangolins simply dig into an anthill to lap up the swarming insects rather than lure them into some fantastical subterfuge.

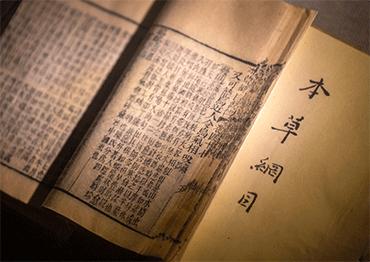

In this way, Li painstakingly completed the first draft of his pharmacological masterpiece, Bencao Gangmu, or the Compendium of Materia Medica in 1578, after more than a decade of field research. He revised the work at least three times right up until his death in 1593. Three years later, the Compendium was officially published in what is today’s Nanjing, Jiangsu Province.

The Compendium contains 1.9 million words, encompasses 52 volumes, describes 1,892 kinds of drugs (374 of which were previously undocumented), 1,192 illustrations, 1,109 drawings, and more than 11,000 prescriptions, making it an unprecedented tome of Chinese pharmacology. It condensed the works of past generations, corrected many previous mistakes, supplemented deficiencies and included many important discoveries and breakthroughs.

It encompasses natural sciences such as medicine, botany, zoology, mineralogy, geology, chemistry and physics, as well as social sciences such as history, philosophy and anthropology, making it a great source of inspiration for future generations. For example, it records that “Artemisia annua (wormwood), bitter and cold in odor, non-toxic, is used to treat malaria and cold fever.” In October 2015, Tu Youyou was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for her discovery of artemisinin and dihydroartemisinin to treat malaria, becoming the first Chinese to win a Nobel Prize in the category.

Due to the limitations of science and technology at that time, the Compendium has some shortcomings. It sometimes oversimplifies the form and origin of some drugs, and the illustrations are roughly drawn. It also makes false claims, such as fireflies are born from the roots of decaying plants. But these deficiencies by no means undermine the overall value of the book.

Old Version

Old Version