Nanjing has played a crucial role in the Chinese economy throughout history. This is why during the First Opium War (1840-1842), the British army sailed directly to Nanjing and strongarmed the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) into unequal treaties.

Because of Nanjing’s strategic position, it was forced to open to foreign merchant ships in 1898 following the Qing Dynasty’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which established Korea’s autonomy and ceded Qing territories to Japan. Before long, Nanjing built railroads, and trains became as vital to the city as carriages and rickshaws.

Xiaguan, a Yangtze River port outside Nanjing’s northern gate Yifeng, was opened to foreign business activities. Prosperity from the port soon spread, transforming Xiaguan into a bustling commercial center, and Nanjing developed rapidly during the Qing’s final years.

For example, Nanjing hosted an international exposition in 1910, the first of its kind in Chinese history. Aiming to stimulate industry and enlighten the public, the event – called the Nanyang Industrial Expo – showcased domestic and foreign products from textiles to machinery and transportation. The exhibition created quite a stir and attracted many notable figures, including seminal Chinese authors Lu Xun and Mao Dun. Lu brought his students there. Ye’s grandfather, a middle school student at the time, visited with his teacher.

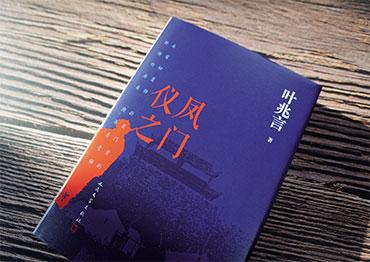

Ye found inspiration for his story about Nanjing’s approach to modernization very close to home, near his apartment at Yifeng Gate (known today as Xingzhong Gate). Built in late 14th century when Nanjing was capital of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the city wall still exists.

In the novel, Ye portrays the bustling prosperity of Xiaguan Port between 1907 and 1927, set against a tumultuous time marked by revolution, uprisings and warfare between warlords.

The novel centers on Yang Kui, a rickshaw puller who seizes the opportunity to build a business empire. Yang becomes swept up in the 1911 Revolution that ended China’s last imperial dynasty and led to the Republic of China’s founding. After the warehouse he opens with friends is requisitioned as a revolutionary base, Yang joins their forces and participates in uprisings across the city.

Amid the turmoil, Yang expands his business from a small warehouse to a commercial complex, supported by his connections in the newly formed government. He rises to prominence in both business and politics, and marries the woman of his dreams. But when Yang undertakes a mission for the revolution, his fortunes take a tragic turn.

“Ye shows the abrasive nature of historical progress and how people’s destinies are shaped by the passage of time,” commented Liang Hongying, editor-in-chief of Literary News, during a seminar for the novel held in Nanjing in February.

“Every era presents unique opportunities. We get a glimpse of today through the past and vice versa. Yifeng Gate could be interpreted as a metaphor for the rise of big companies like Alibaba, Xiaomi or Suning in contemporary China,” Ye told the Shanghai Observer, a news app affiliated with newspaper Jiefang Daily.

“The story has two plotlines – one focuses on Yang Kui’s trials, while the other, more subtle narrative explores the modernization of Nanjing,” noted Wang Chunlin, a professor with Shanxi University, at the seminar.

Instead of depicting heroic figures in history, Ye focuses more on the fate of ordinary individuals during social transformations who experience rises and falls beyond their control. In The Flower’s Shadow, for example, Ye portrays a woman who becomes head of her influential family after the death of her father and brother in Republic-era China. During a time when many of the social constraints imposed on women in feudal society were relaxing, she openly challenges these taboos, and puts her life at risk.

In Yifeng Gate, Ye illustrates the plights of ordinary people as they struggle to survive in turbulent times, and their indifference toward regime change.

“This detachment of Nanjingers stems from their yearning for a peaceful life and their resilience after suffering,” noted Liu Daxian, a research fellow with the China Academy of Social Sciences, at the seminar.

Old Version

Old Version