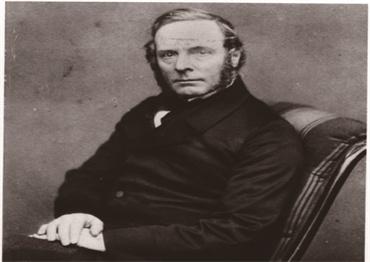

Although the British established tea plantations in northeast India’s Assam in 1830, the quality of tea produced in India was poorer than that in China. The British East India Company engaged Scottish botanist Robert Fortune (1812-1880), director of the Royal Botanic Gardens in London, to make a clandestine trip to China to steal the closely guarded secrets of growing and producing tea.

In 1848, Fortune arrived in Shanghai via Hong Kong and hired a Chinese assistant surnamed Wang. He disguised himself in Mandarin robes and a longbraided cue made of horsehair, the officially sanctioned hairstyle for men during the Qing. Fortune and Wang made their way to Hangzhou in East China’s Zhejiang Province, where they visited a green tea plantation and learned production techniques.

Afterwards, they traveled to Wang’s hometown in southern Anhui Province, where Fortune acquired tea trees and seeds. In January 1849, Fortune sent the first tea seeds and seedlings to British-occupied India. Because of the long voyage and shoddy transplanting, only 80 out of the 15,000 seedlings survived, and none of them grew. Fortune’s first attempt was in vain.

Undeterred, he embarked on a second expedition. His mission was to obtain black tea from the Wuyishan Mountains in southeast China’s Fujian Province, a major tea producer. This time, disguised as an official from northern China, he discovered Da Hong Pao, the highly prized Oolong tea grown in the gaps of mountain boulders that create its signature mineral taste. During this trip, he studied the differences between black and green teas, as well as tea horticulture and production.

In February 1851, Fortune and eight master tea growers departed from Shanghai for Calcutta (now Kolkata) with 16 huge glass cabinets filled with tea seeds collected from Zhejiang, Anhui and Fujian, as well as tea production equipment and tools.

Over the following decade, world-class black teas were cultivated in Darjeeling in the Himalayas from the trees and seeds Fortune took. China’s monopoly on tea was broken. After returning to Britain, Fortune published A Journey to the Tea Countries of China, a memoir that recounted his story of economic espionage.

The British not only established tea companies and plantations in Assam and Darjeeling, but also touted tea produced in India as “pure” in contrast to the “poisonous” and “insidiously invasive” tea produced in China.

British scholars even turned tea into a “purification” movement for intellectual colonization and British-Indian agriculture. They defined the 19th century as the inauguration of British writing the history of tea, declared tea as the epitome of “British values” and falsified the origins of tea from China to Britain.

The British government sent Fortune to steal the secrets of tea production from China and plant Chinese tea in its Indian colonies to make Britain less reliant on trade with China. While glorified at the time, later generations in the UK, US and other European countries reexamined Fortune’s legacy.

In her book For All the Tea in China, American author Sarah Rose dubs Fortune “a plant hunter, a gardener, a thief, a spy.” What Fortune did in China is arguably among the greatest theft of trade secrets in history, on a par with stealing semiconductor technology or the recipe for Coca-Cola.

Old Version

Old Version