Despite the wow factor of the new venues, many worry they will become white elephants after the Games, a well-known issue where costly Olympic stadiums and facilities are underused or fall into disrepair, a fate seen by venues after Athens 2004 Games and Sydney 2000. Post-Games use has become a key concern and challenge for Olympic organizing committees.

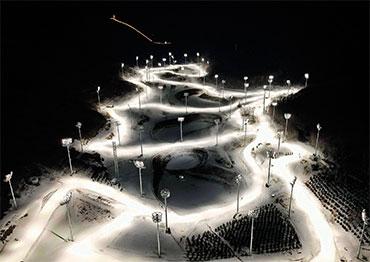

According to the plans of the Beijing Organizing Committee of the 2022 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, the new snow sports venues will remain in use as training venues for domestic athletes and will continue to host international competitions. The competition zones include ski runs and facilities for public use outside competitions.

China has experience in post-Games use. The National Stadium or Bird’s Nest, and the National Aquatics Center, known as the Water Cube, were built for the Summer Games in 2008. Both venues have been successfully turned into two multifunctional centers for tourism, commercial activities and public entertainment. The Bird’s Nest is the site for the opening and closing ceremonies of the Winter and Paralympic Winter Games, and the Water Cube, renamed the Ice Cube for the Games, is the venue for curling. According to a Beijing News report published on the 10th anniversary of the opening of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games on August 8, 2018, the National Stadium has transformed from being dependent on tourism, which provided 95 percent of its revenue in 2009 to commercial events providing 75 percent of total revenue in 2018.

During that decade, the National Stadium received some 32 million visits and hosted over 600 events, and the National Aquatics Center 20 million visits and 1,200 events. Some two million people have used the Water Cube’s swimming facilities.

But post-Games use of Winter Olympic snow facilities will be harder, as many sports are not popular and even little-known in China.

“The public in some countries like to watch ski jumping competitions at the club level or even try out smaller jumps themselves, but China doesn’t have these kind of clubs or accessible jumps, so it’s hard for the public to participate,” Wang Jingxian told NewsChina. “Even professional Chinese athletes are not so good at snow sports, though they are strong in ice sports. Only one of the 13 gold medals the Chinese national team won in previous Winter Games since they first participated in 1980 was in snow sports,” he added.

While China did not see medal success in Alpine or Nordic skiing, it does have world beating freestyle skiers and snowboarders in teenagers Gu Ailing Eileen and Su Yiming, which may go some way toward boosting post-Games interest, particularly among young people. Wu Bin, founder of a Beijingbased ski business and deputy chairman of the Beijing Ski Committee agreed with Wang’s assessment. Only regular skiing and snowboarding see much public participation, and there is no demand for other disciplines like ski jumping and cross-country skiing.

“Although there are more than 700 public ski resorts throughout the country, most are in poor condition and of low standard,” Wu said. In his 2020 report on the Chinese Skiing Industry, Wu found that China only had 28 skiing fields with a vertical drop of over 300 meters, and these resorts attract 17 percent of total customers.

Wu believes the biggest challenge for the Snow Swallow is whether it can attract enough customers post-Games to cover the cost. “It’s not a problem that we’ve built a ski field for higher-level skiers, but it should be noted there aren’t very many advanced skiers [in China],” he said, adding that a balance should be struck between the needs of professional athletes for high-standard facilities and those for amateur skiers.

More difficult and dangerous, sliding sports have little public participation anywhere. There are only 16 icial luge tracks in the world.

According to Zhang Yuting, they plan to turn parts of the Snow Dragon into a commercial center and a research center for ecological restoration. They also designed a public zone where the track’s vertical height difference falls to around 40 meters, much lower than those for professional athletes at 121 meters.

Even so, the equipment is very expensive – NBC reported that an Olympic bobsled can cost anywhere from US$30,000 to US$100,000. It is not known what the public interest would be or how much a ticket would cost to try a sliding sport.

Zhang Li does not think that snow sports alone will support post-Games use of the new venues. Many ski jump venues were dismantled after Winter Olympics, including those built near Sestriere, a winter sports destination in the Italian Alps and one of the venues for the Turin 2006 Winter Games.

That is why the Snow Ruyi has a multifunctional space above the jumps, which includes a restaurant which will be used for tourism, conferences and exhibitions, Zhang Li said. There are steps alongside the jumps to allow hiking as well, and a standard soccer pitch down in the valley.

Inspired by Swiss experts, the designers built a three-kilometer-long elevated circular path called the “Ice Jade Ring” which links the Snow Ruyi, the biathlon center and the cross-country ski center which will be used for leisure and hosting mountain bike races.

“Post-Games use means turning a venue designed for superstars and professional athletes into one for ordinary people,” Zhang Li said. A key indicator to measure post-Games potential will be if people can spend 2.5 hours visiting and using the facilities such as the Ice Jade Ring.

“We have to see how a building grows and serves people and society after it starts being used by the public,” Zhang Li said. “The new venues will be tested in the Olympic Games, but another test is five to 10 years after the Games to see how much they can integrate into people’s lives... Time is the test of a building’s idea, design and construction,” he added.

Old Version

Old Version