uthor Yu Hua sits on a bench in a little run-down restaurant in his hometown, Haiyan, Zhejiang Province. With a slight frown, the grey-haired, middle-aged Yu stares at his smartphone, then shouts. The camera switches to his phone, revealing the source of his sudden excitement – an NBA game.

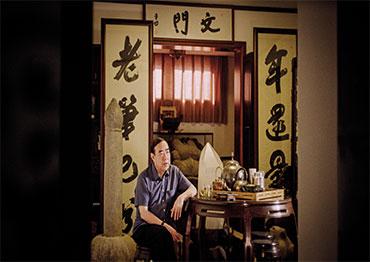

The scene from Jia Zhangke’s documentary Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue features some of the director’s favorite devices: an ordinary Chinese face, a public location with a bit of history, and a sudden intrusion of new technology and globalization. Such snippets of daily life seem otherworldly under Jia’s lens. Among China’s contemporary filmmakers, Jia is famous for capturing the realistic textures of ordinary Chinese life. This time, his subjects are writers.

Released on September 19, Swimming Out features interviews with three leading figures in contemporary Chinese literature – Jia Pingwa, Yu Hua and Liang Hong. Through their personal stories, they narrate the changes in rural Chinese society over the second half of the 20th century. Told in 18 chapters through the intimate accounts of writers, Jia explores the Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s, the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), and the booms in urbanization and migration since 1978.

On September 9, Jia sat down with our reporter at his studio in Beijing to talk about his latest film, his views on film and literature, the rise in moralism toward art and literature, cinema during Covid-19 and the decline of globalization.

NewsChina: Besides interviews with writers, you also focus on the minor details of everyday life, a theme found in many of your works. What attracts you to these images?

Jia Zhangke: Film is a vehicle that manifests our world in the most direct way. Images of real life create a documentary-like aesthetic. Such beauty has always drawn me – real, vivid and natural. It’s often said that the art of cinema has two traditions: the realistic and the theatrical. But film is best at recording and documenting things.

NC: You’ve said this film aims to record the “mind” of Chinese people. In the film, several writers narrate their personal experiences during times of drastic change – periods you addressed in previous works. Have their stories changed your views on these times?

JZ: Compared to [the film’s subjects], I was more familiar with small town life. Though small towns are near the countryside, living in a small town is distinct from living in a village. During the planned economy, towns and villages were entirely different worlds. This film was mainly about the experiences of rural life in China.

For instance, their stories gave me new insight on starvation. I suffered from hunger as well. There was no variety in what we ate during my childhood. The only food I had to eat was wowoto (a kind of steamed corn bread), which didn’t have many calories, so I felt hungry all day. While shooting this film, I discovered that every generation experienced hunger. It was thought that people born in the 70s didn’t experience hunger like that anymore. But Liang Hong, who was born after the 1970s, talks about her experiences with childhood hunger. I learned that anxieties over hunger permeate China’s history.

NC: Among the three writers you interviewed, whose works influenced you most?

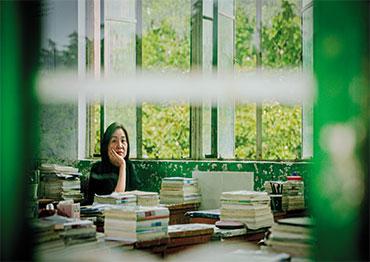

JZ: Comparatively, Liang Hong influenced me more. I read Jia Pingwa’s fiction in high school in the early 1980s. I read Yu Hua’s To Live when I graduated from high school. His avant-garde writing really drew me in. By the time I read Liang Hong’s non-fiction best sellers Leaving Liang Village and China in One Village, I had directed my interest to non-fiction film. I filmed documentaries 24 City (2008) and Wish I Knew (2010). I related to Liang’s works deeply. Migration, urbanization, rural migrants, the decline of rural areas and the disappearance of villages – we all faced the same problems. I’ve given my responses in film, and she did in literature.

Film is not an isolated art. Film and literature are both a part of culture. There is a spiritual understanding and resonance between filmmakers and writers. We have much in common and also many differences. There’s an inner dialogue between us when we read or watch each other’s works.

NC: Do you think the relationship between Chinese film and literature has changed?

JZ: In the 1980s and early 1990s, Chinese cinema and literature were closely connected. Many films were direct adaptations of books and saw groundbreaking success, such as Red Sorghum (1988), Raise The Red Lantern (1991), Farewell My Concubine (1993) and To Live (1994). These films usually feature how the tumultuous changes in modern Chinese history affected individuals. They are mainly talking about the past.

As the market economy deepened in the 1990s, society changed more drastically. Many directors, including me, had never adapted movies from books. That doesn’t mean that I don’t like fiction. It’s just because I have my own observations and feelings about the present. So I prefer to create stories based on my own feelings.

As Chinese cinema commercialized in the 2000s, more filmmakers turned to genre films. Many of these commercial movies were adaptations of pop fiction and web novels instead of serious literature. But there are still some realist directors who seek to express their feelings, including me. I keep filming the stories I write, because I have something to say.

NC: Are films adapted from serious literature becoming marginalized and even disappearing from Chinese cinema?

JZ: They aren’t disappearing, but their influence has noticeably faded compared to the 1980s and the 1990s, when film and literature interacted so closely. In the 1980s, cultural resources in China were scarce, so artists in film, literature and other mediums cooperated more often to support each other. In today’s culturally diverse age, the intimate relationship between different art forms has weakened.

Furthermore, nowadays people consume more diverse forms of entertainment. People in the 1980s had very strong spiritual needs. They loved to read fiction and poetry, since life was so simple. Today, things like karaoke and football fills those needs. Things have changed immensely. We can’t say whether it’s good or bad. It’s just changing.

NC: There is a recent streak of moralism used to criticize and reevaluate literature and arts. Many equate values of fictional characters to the writer’s own, and condemn complicated, morally questionable love or marital relationships portrayed. As a creator, are you affected by this trend?

JZ: No. I’ve said it before – undue moralism means the rise of fascism. I think we have entered an era run by public opinion. Popular opinions and feelings have taken the wheel in managing society. Many hidden opinions of the past are now exposed and aggrandized by the internet to form an enormous public forum. Under these circumstances, artists have to stick to things they believe in. They can’t manage society, only themselves.

In this chaotic era of opinion, creators should stand with their principles even more. Artists should become people of principle. Why bother with opinions? The times call for us to become the stubborn ones. Of course, everyone may feel a bit lost living in times like these, but I always tell myself that I have to become a stubborn person.

NC: Don’t you worry that your stubbornness may incur lots of negative criticism?

JZ: Then I’ll quit and go back home. No big deal. I don’t worry at all. Self expression is of the greatest importance to me. It’s my job. Making films is extremely energy and resource consuming. You work tirelessly on one project day and night for two or three years, and all you hope for is to project your own self through it. For creators, what’s the point of making a film if we’re deprived of that?

NC: You once said that you have no interest in forming public consensus. Do you still think that?

JZ: Of course. Different people have different roles. I’m a creator, and it’s not my job to form a public consensus. We’ve made detours over history, always trying to persuade others through battles of opinions. Then it turned out fruitless and exhausting, with nothing good coming out of it. Solving these problems takes time, bit by bit. A creator is not a debater. Today, many people love to debate. But I’m a filmmaker. All I need is to follow my road.

NC: As cinemas saw massive closures following the Covid-19 pandemic, some famous filmmakers and actors turned to online releases. What do you think of the relationship between big-screen and smallscreen films?

JZ: After the outbreak of the pandemic, I was supportive of all creative mediums, not just movies made for theaters. Cinemas closed, opened, and then closed again. The entire film industry faces a serious crisis. It is quite understandable that many filmmakers turned to online streaming platforms.

But from a more conservative point of view, I definitely cherish cinemas. Films have two qualities that small-screen video cannot replicate: the first is its magnifying effect. Film’s humanity manifests through magnification. When a peasant’s hands are projected onto a big screen, the magnifying effect creates a sense of reverence. Human suffering, sorrow, a mother’s woe – all these emotions are magnified. Think about when film was just invented, when the audience saw a person’s face enlarged to the size of a wall. That must have been an incredibly shocking experience. When we think about cinematic art, it’s best to go back to its beginnings to understand it.

The second is the finale. Cinema… creates a sense of ceremony. Watching a film in cinemas is a collective experience in the darkness. Such an effect can’t be recreated on the small screen.

Video-streaming platforms have sponsored Swimming Out Till the Sea Turns Blue, and did suggest releasing it directly on their platforms. But we still insisted on allowing some audiences to experience it on the big screen first. I’m conservative on this point. Cinematic language was created for the big screen. The space, storyboard and sound design are all imagined for big screens. Small screens cannot fully realize my ideas.

NC: When you filmed The World (2004), you expressed deep anxieties and doubts over globalization in it. Now, many worry about the ebbing of globalization.

JZ: Like you say, I had anxiety about globalization around the turn of the millennium. I remember one time when I visited my sister’s family. My middle school-aged niece was a pop music fan and had an enormous collection of albums, but not a single one from a Chinese artist.

I asked her, ‘Are you sure you can’t find any Chinese song you like?’ She answered, ‘I don’t know. I just don’t really pay attention to them.’

I had concerns about the impact of globalization on our own culture. But now, particularly during the Covid-19 epidemic, there is a rising anxiety around the world over the ebb of globalization. The gateway of cross-cultural communication has almost closed. Also, tumultuous changes and uncertainties in global politics have deepened people’s concerns.

Everything has two sides. Globalization brings both benefits and anxieties. We are those people who remember to check the flip side. When globalization forcefully burst open the country’s door like a storm, we saw the flip side of this force, that it may incur the decline of people’s confidence in their own cultures.

But now, as globalization recedes, we should also see the flip side of this phenomenon: the door that led to rich and fruitful cross-cultural communication has closed. People of different cultures should maintain a dialogue with the world.

Film naturally has roots in globalization. Visual language transcend words. Why are there so many international film festivals in the world? Because film is a product of globalization. Thus, filmmakers are very sensitive to the decline of globalization.

Old Version

Old Version