“If this flooding had occurred 10 years ago, we might have seen much worse devastation,” Ren Yimin told NewsChina.

In 2012, many important relics were in decay.

From 2012 to 2014, slogans about “rescuing ancient architecture” drew attention from the public and media. Reporters flocked to Shanxi. Tang Tianhua wrote nearly 50 letters to authorities, each reporting a unique problem he discovered from his many visits to the province.

In early 2015, Half-Hour Economy on CCTV-2, one of China’s most influential financial television programs, broadcast a fourepisode feature about the bleak reality of the cultural relics in Shanxi.

Under pressure, in March 2015, the provincial government said it would raise 150 million yuan (US$23.4m) in five years to restore the 235 national and provincial protected ancient structures. Local media dubbed it “life-saving money for ancient buildings.”

According to statistics from Shanxi Provincial Cultural Relics Bureau, from 2016 to 2019, 106 million yuan (US$16.6m) was allotted from the central and provincial governments for the conservation of 358 cultural sites in Shanxi – most of which were protected at the State or provincial level. After years of efforts, the ability to withstand disasters at the most prominent sites and structures has been greatly enhanced.

Ren said the previous funding system was to let governments take responsibility for relics under their protection: The central government provided funding for nationally listed ones, the provincial government for provincial-listed relics. It was the county governments that took responsibility for relics that were yet to be assigned protected status.

“Though there are different conservation levels for relics, in essence there shouldn’t be a difference,” Ren said.

A funding policy started in 2019 encouraged central and provincial government funding to be allotted to the conservation of lowergraded cultural relics.

Bai Xuebing, director of the Relics Department of Conservation and Utilization of Cultural Relics of Shanxi Provincial Cultural Relics Bureau, told NewsChina that provincial government funding is still basically used to preserve provincial-listed relics. “But the conservation of lower-graded cultural relics is the next focus of the provincial government. More resources will be allotted to the lower-graded ones,” he said.

Bai admitted the problem is still the lack of money. For a province with over 280,000 historical sites, it is impossible to rely on government funding to cover all the costs of conservation. So authorities have looked for other ways.

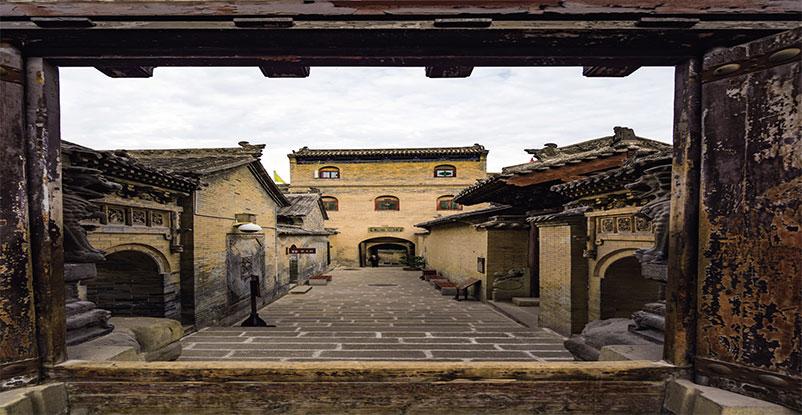

In 2010, Huang Wensheng, an entrepreneur from Woxian County in Shanxi, signed an agreement with the county government to “adopt” a county-graded site – the Xihai Dragon King Temple. Built in the Yuan Dynasty, the temple had long been abandoned and was choked with weeds. Huang put 4.5 million yuan (US$703,274) toward its restoration and opened it to the public. He has been granted the right to use the temple for 20 years.

It was the first instance of “cultural relic adoption” in Shanxi. Since 2017, the model has been promoted throughout the province. Enterprises and individuals who adopt ancient relics should take responsibility for the restoration and have the right to develop museums, exhibition halls or small-scale entertainment venues around the site. Ancient residential houses and courtyards, once adopted, can be used as small inns, guesthouses and stores. The development should not endanger the safety of the ancient structures.

So far, 238 cultural relics in Shanxi have been adopted by social organizations.

However, these adoption programs have also led to improper restoration, overdevelopment and neglect. Moreover, many historical sites in more remote areas have less commercial value and draw little attention.

As a result, cultural relics are disappearing. According to the third national survey on immovable cultural relics, which was conducted from 2007 to 2011, more than 44,000 immoveable cultural relics had disappeared compared with the second survey (1981-1989), 2,740 of which were in Shanxi Province. Most were unlisted.

“It’s a debt we have to own,” Zha Qun said with a sigh.

In 1997, Zha spent a month visiting different regions of Shanxi to do field research. What impressed her most were the little temples quietly hidden in the villages, ancient and fragile.

During her inspections after the deluge, Zha revisited the areas she had been to 24 years ago, but found that many places have become “hollow villages.” The village temples are completely deserted and thick with weeds.

Tang Tianhua shares the same feelings about the empty villages. Sometimes he can barely find a single person to ask for directions. In most of the villages, only the elderly remain. “Even 50-year-olds are considered young,” Tang added.

“Architecture is made for people to live in. Once wasted, the building becomes dilapidated really quickly. Daily maintenance is indispensable. Things would be entirely different just with some minor care and renovations now and then,” Zha said.

Old Version

Old Version