But after formulating ambitious plans, offering subsidies for buyers of hydrogen-powered vehicles and building refueling stations, some experts are asking if this will be another example of local authorities burdening themselves with yet more white elephant developments.

The central government started offering subsidies for hydrogenpowered vehicles in 2009, but the process has been slow. The major issue is that hydrogen power is yet to be fully recognized as energy, having always been treated as a volatile element. Only in April 2020 was hydrogen defined as a source of energy in a draft Energy Law. Although not yet legislation, the draft was seen as a green light for expanding the hydrogen gas sector. Still, the production and use of hydrogen, though included as part of the vision for new energy vehicle manufacturing, has no overall strategic plan at the national level.

China has hastened the development of hydrogen-related industry through incentives, particularly since 2019. First there were subsidies for purchasing fuel cell cars. In 2020, the subsidies were replaced with awards for cities that do well in making breakthroughs in core parts, introducing skilled personnel and setting good examples in industrial application. But the difficulties start when these places try to source sufficient supplies of hydrogen.

A byproduct of the fossil fuel sector, 96 percent of hydrogen in the world is derived from coal or natural gas. In China, hydrogen at refueling stations is mainly a byproduct of industrial processes, previously seen as waste. Even though some places, like Shandong and Sichuan provinces, claim to be big producers of hydrogen, the amount available for fueling vehicles is limited.

Transporting hydrogen is a big problem. It is usually transported via tube trailers – long tanks filled with compressed gas hauled by trucks. But hydrogen made from industrial processes is not suitable for long-distance transportation. “Using tube trailers for long-distance transport is uneconomical, but building pipelines costs too much,” said Ouyang Minggao, an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and vice president of the China Electric Vehicle Association. He said that current transportation methods are inefficient and costly, and the technology needs upgrading.

In cities that aim to develop fuel cells to power vehicles, hydrogen supply is the priority. However, anxiety over refueling is hindering development, Jing said.

Infrastructure development also faces challenges. By the end of 2020, China had built 118 refueling stations for hydrogen, 101 of which are operational, according to the Orange Group, a research institution specializing in hydrogen fuel cells. The number is expected to reach 1,500 in 2035 and 10,000 in 2050, according to a 2019 prediction from the China Hydrogen Alliance, a national-level think tank dedicated to promoting the development of the hydrogen industry.

Gao Huiqiang, chief manager of the fuel cell platform of Maxus, a subsidiary of the Shanghai-headquartered SAIC Motor, told NewsChina that an electric vehicle battery charging station costs from tens of thousands up to hundreds of thousands of yuan, but a hydrogen refueling station costs much more.

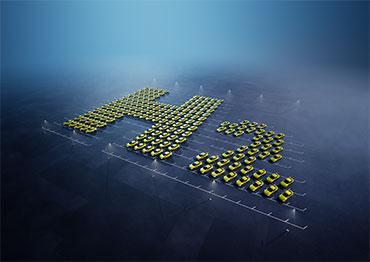

Gao Dingyun, chairman of Shanghai-based Sunwise, a company engaged in hydrogen-related technology, said that maintenance costs exceed 2 million yuan (US$306,000) a year. Most refueling stations do not make money due to the high cost of gas and lack of demand. There are fewer than 10,000 hydrogen-powered cars on the road.

The cost of running hydrogen-powered vehicles is daunting too. In Weifang, Shandong Province, a refueling station dropped the price of hydrogen to 50 yuan (US$7.7) per kilogram (usually 80-100 yuan per kilogram) with subsidies from the local government. But operating costs are still higher than traditional vehicles. “The price needs to drop more, to at least 35-40 yuan (US$5.4-6) per kilogram, to be as competitive as traditional vehicles. But no city can achieve that yet,” said an employee at Weichai New Energy, a new energy technology firm in Weifang.

When it comes to the middle of the industrial chain, China has to import hydrogen fuel cells, which help transfer the chemical energy produced by hydrogen and oxygen into electricity. Lu Bingbing, general manager of Shanghai Hydrogen Propulsion Technology, a SAIC subsidiary producing fuel cell technology, told NewsChina that the core of a fuel cell is a fuel cell stack, and the heart of that is the membrane electrode assembly, which decides service life and performance. The membrane electrode assembly accounts for 70 percent of the cost of fuel cell stacks.

He said that after years of efforts, the auxiliary parts of fuel cells can be produced domestically. But China relies on imports for three core materials to manufacture membrane electrode assemblies. “Domestic companies are striving to fill the gap, but the technology lags behind,” Lu said.

In recent years, domestic fuel cell technology has largely improved. Gao Huiqiang said that when Maxus were developing their first hydrogen fuel cell car five years ago, it was hard to find even an air compressor supplier and they had to import them in the end. “Now there are many choices and the products have improved in both quality and cost.”

Ouyang Minggao agreed that the products have improved a lot in terms of main indicators, including service life. A domestic chain to produce fuel cell parts has taken shape and the next step is to reduce the cost of fuel cell systems by 80 percent.

But Jing said there are still gaps with international manufacturers. “The core technology and materials for fuel cells are still in the hands of developed countries such as Canada, the US, Japan and South Korea,” Jing said. She suggested enterprises focus on improving the weak points in core technologies and materials to break the bottleneck, instead of hurrying to expand the market.

Old Version

Old Version