Pop megastar Li Yuchun talks with NewsChina about the changing landscape of China’s entertainment industry and fan economy, as well as her struggle to overcome years of labeling by critics and her ceaseless pursuit of self-expression

“Today, being an idol is a kind of service,” says former Super Girl champion Li Yuchun

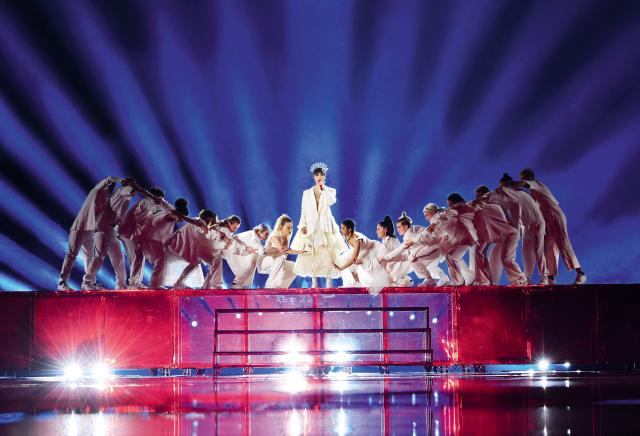

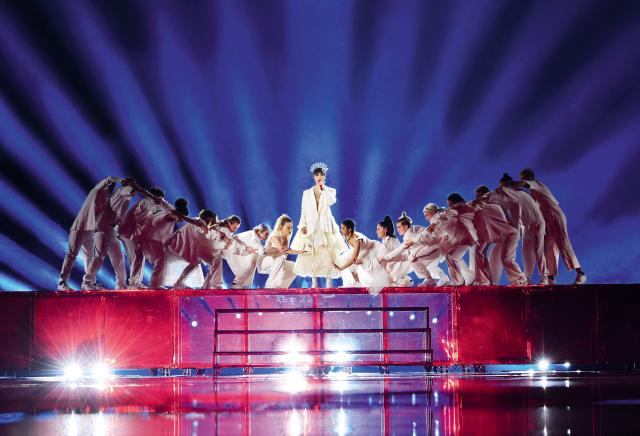

On the last day of 2019, Li Yuchun closed out the 2020 Jiangsu TV New Year Countdown Gala with her song “Wa.” “Background, job, identity, gender, skin color… / all these things have nothing to do with love / all these things have nothing to do with me,” she sang.

Li sang “nothing to do with me” over and over again. Dancers circled her and removed the crown she was wearing. Li then took out a tissue and wiped off her lipstick.

She had specifically told the gala’s director to get a close-up shot of her doing that.

In the summer of 2005, Chinese audiences crowned their first pop icon on live TV. Li, then 21, had won Super Girl, a singing competition where viewers voted for their favorite by text message.

Li stood out from the other contestants not only in talent. Her tomboy look and relatively masculine stage presence was considered a bold statement against China’s gender norms that millions of fans embraced. Lee later appeared on the cover of Time magazine’s Asian edition, which called her a “hero.”

But Li, known also by her stage name Chris Lee, sees herself more as a musician. Since her Super Girl victory, she has released 10 studio albums, scored more than 60 chart-topping songs and starred in award-winning feature films

Her unique, androgynous style almost single-handedly made gender-neutral aesthetics cool in China. But her challenge to China’s prevailing beauty standards and gender conventions made her a target of cyber violence for over a decade.

For years, the press and social media have labeled Li an “idol,” “megastar,” “grassroots,” “trendsetter,” “androgynous,” and a “feminist.” Her New Year’s TV performance openly challenged them all.

Born in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, Li comes from a working class family. Her father was a police officer and her mother a teacher.

In 2005, Li was a third-year vocal major at the Sichuan Conservatory of Music determined to pursue a singing career in Beijing after graduation. But that summer, her fate changed when she tried out for the second season of Hunan Satellite Television’s Super Girl.

Super Girl was already a hit, but producers added a new element for the second season: the audience could vote via paid text messages – a first for Chinese TV. Fan clubs formed online and offline. Street teams campaigned for their favorite contestants. In major cities, club members canvassed shopping malls, subway stations, parks and other public spaces for votes.

Li saw the highest support among the contestants. Her loyal fans, who called themselves yumi, meaning “corn kernel” – a portmanteau of her given name “Yuchun” and the word for “fan” – were the most active.

The season finale brought in 400 million viewers. Li received 3.52 million votes – unprecedented in the history of Chinese pop culture. “It was not called a ‘talent show at the time. We just saw it as a stage that allowed a group of people who loved singing to perform. We didn’t know what was waiting for us ahead,” Li told NewsChina.

“A couple of days after the finale, it gradually occurred to me that I couldn’t go back to my old life anymore.”

The success of Super Girl spawned the nobody-to-megastar model that later swept the country. The idol industry and fan economy grew in the Chinese mainland. Talent shows boomed, and companies such as EE-Media, Yue Hua Entertainment and Wajijiwa Entertainment began grooming future idols.

By the time Super Girl ended in 2011, smartphones brought idol worship and fan culture on social media to a new level. Fans would organize and buy multiple copies of a new release to boost idols’ chart positions and crowdfund campaigns to promote their latest projects. Stars and their companies embraced it, giving fans a direct role in influencing their favorite artists’ careers.

Li compared the trend to 1980-90s idols like singer/actor Leslie Cheung, one of the biggest stars of the Hong Kong entertainment industry before his suicide in 2003.

“The concept of what an idol is has changed. In Leslie Cheung’s time, idols had strong personalities and could lead people with their extraordinary charisma and could create original work. But today, being an idol is a kind of service. Fans dictate their personas. They need to present a personality that caters to expectations. Otherwise their fans unfollow them,” Li said.

In 2017, Li was invited as one of three coaches on music talent show The Coming One for streaming platform Tencent Video. But she became disillusioned after shooting the first episode. “I found that many contestants didn’t really love music. They used music as a weapon to become famous,” Li said.

Unlike her own experience on Super Girl, Li found that most contestants on The Coming One were clear about what the show could do for their careers. “They knew what television exposure would bring about – a chance to become famous overnight. Many prepared a lot for it. They knew their strengths and weaknesses, and carefully calculated what to perform and what to hide from the camera,” she said. While talking with contestants on The Coming One, Li found that many had already signed with talent agencies, which provided professional singing, dancing and acting training. Some had already been on talent shows. “No matter what, they have their ways of winning,” Li said.

Zhang Pei, managing director of The Coming One, told NewsChina that the program assigned every contestant a “personality writer” to help create for them a more appealing personal backstory. “It’s very possible that fans will forget about contestants before they show their real selves,” Li said.

Despite her popularity, the industry was not quick to welcome Li. Singers who shot to fame on reality TV programs were usually considered unprofessional and vulgar in the industry.

Li faced prejudice from both the industry and the public. Some celebrities openly criticized her vocal talent. Some television stations would cut her performance or replace her with other performers. Until 2013, China Central Television (CCTV) did not invite her to perform on the annual Spring Festival Gala, one of the country’s most-watched shows since the 1980s.

Li responded with hard work and patience. She has written and produced many of her nearly 80 career singles. But it was her fourth album, Chris Lee (2009), that marked a new phase of self-expression. On track “Lai Fu” (“A Beautiful Song”), she gives lip-synching artists a tongue lashing. In “Bad Student,” she voices her support for students labeled as bad based on their poor academic performance, and challenges China’s exam-oriented education system. “Why Me” is about her unyielding defiance when she deals with criticism and attacks.

Over the past three years, she has taken on issues such as the relationship between individuals and society.

At the Venice Art Biennale 2017, Li was inspired by avantgarde artist Guan Xiao’s work “David,” a video on the role and influence of Michelangelo’s “David” outside of Europe.

“Everybody visits the museum, eager to glimpse David. They discuss him as if trying to devour him, but no one knows who he really is. I found the video quite interesting. I sat there and spent a whole afternoon watching it over and over again,” Li said.

The work reminded Li of her own situation: an object being defined and labeled. Soon after, she released her ninth album Liu Xing (Pop). For the first time, she wrote the lyrics for an entire album.

The title track explores how people deal with social media. In the video, Li repeatedly sings “I am the boss” while wearing a bunch of gold ropes and chains on her neck – a tongue-in-cheek reference to her idol status.

Her latest album Wa (2019) revolves around Li’s criticism of defining societal labels such as gender, class, race, occupation, status and family background.

When asked about dealing with “being defined,” Li responded: “Have I not been troubled by this all the time? Have I not been troubled by gender stereotypes? Have I not been attacked? Haven’t all girls been affected by so-called defined roles today, be it at the workplace or among family? Have people not always judged others based on their background, gossiping about who is rich and who is poor? People talk about this stuff all the time but they seldom write it in pop songs. After all, many think pop songs are about nothing but love, love, love.”

Li’s unisex look and tomboy persona made her a high-profile target for cyber violence in the early days of Chinese social media. Netizens called her “Brother Chun” and posted images of Li’s face photoshopped on the bodies of masculine-looking men.

Li was reluctant to go into detail about her experiences.

“The violence was too much to be talked about. All my suffering made me stronger and become what I am today. I protect myself from the chaos, just calmly observe and think, and I believe someday these scars will become an explosive force in my work,” Li told NewsChina.

“If I can’t write ‘goddamn’ in my songs, perhaps I can say it through the mouths of characters I portray,” Li said of her forays into acting

Li has also ventured into film, scoring leading roles in big-budget movies such as Hong Kong director Teddy Chan’s Bodyguards and Assassins (2009), Tsui Hark’s The Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (2011) and Andrew Lau’s The Guillotines (2012).

Last year she participated in Zhejiang Television reality show I am the Actor II, where she competed against Li Bingbing, Zhang Guoli, Guo Tao and Qin Hao.

“When you make pop music, you’ve got five to eight minutes to express yourself. When what I want to express takes longer, I’m also very interested in attempting different forms of expression,” Li said about joining the show.

“If I can’t write ‘goddamn’ in my songs, perhaps I can say it through the mouths of characters I portray.”

Li often refers to herself in the third person, which she says gives her a detached perspective.

“The public knows her name and knows the existence of this being, but they don’t know her feelings. When she performs the emotions of different characters, she is actually showing her own feelings as well,” Li said.

She sets a clear demarcation between her two identities: Chris Lee, who attends top international film festivals and fashion shows, and Li Yuchun, who likes to cook a bowl of noodles for herself after a hard day’s work.

In contrast with Lee, Li lives a quiet life. She seldom attends parties and usually goes straight home after work. She loves trying out new recipes at home with food delivered by her driver. When she has time, she visits art exhibitions or watches movies – particularly the work of Japanese director Hirokazu Koreeda and Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi.

Li said her grassroots origins are what keep her grounded in the glitzy entertainment industry. “I never see myself as a star. That’s one reason I think I’m different from other celebrities. Many celebrities, as I observe, naturally see themselves as a star in their everyday lives. They identify as their public persona. But I think they’re totally different,” Li said.

Soon after her performance at the 2020 New Year Countdown Gala, Li quickly took off her makeup and flew back to Beijing. The food her driver had delivered was already waiting for her at home. That night, Li had hotpot for one.

Old Version

Old Version