China rebuilt its legal system following the destructive Cultural Revolution. Those efforts continue today in the push for ‘socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics’ that emphasizes equality and human rights

Keep surviving, survive like the animals we are,” Qin Shutian told his lover Hu Yuying before being dragged off to prison.

This heart-wrenching scene comes from the film Hibiscus Town (1987), which through this tragic couple portrays the impact of the “Four Clean Movement” (1963-1966) and the ensuing Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) in a rural community in China’s south.

The scholarly Qin, a former director of the county-level culture bureau, was labeled a rightist during the political campaign. Hu, who had accumulated wealth by selling rice tofu, was marked as a “bourgeois rich peasant.”

This placed them among the Five Black Categories, or groups considered enemies of the Revolution. The others included landlords, counter-revolutioniaries and “bad elements.” Qin and Hu were forced to sweep the streets as punishment. As time went on, they developed feelings for one another and eventually decided to marry.

But just as their labels had brought them together, they also tore Qin and Hu apart. Their application was rejected on the grounds they sought marriage “to spite the proletariat.”

“Is there a law banning marriage between the Five Black Categories?” Qin cried.

“You can’t even forbid hens from marrying roosters or hogs from marrying sows!”

Qin’s outburst seals his fate: On a rainy day, a kangaroo court assembles in the town square. He is sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Alone and with her wealth confiscated, Hu has no means of survival without the help of some kind-hearted townspeople.

The film was no exaggeration. Rule of law and the Constitution were cast aside for an entire decade. People were found guilty without trial. Torture and abuse were rampant.

An estimated two million unjust trials occurred during the tumult of the Cultural Revolution, Jiang Yongqing, an associate researcher at the Party History and Document Research Office, wrote in an article published by the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in 2014.

“Legislation was suspended from 1957 to 1966, and was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution,” Xu Xianming, law expert and president of Shandong University, told Party paper the Guangming Daily in 2011.

China’s first law to pass was the Marriage Law in 1950. Over the next few years, the government focused on other legislation and drafting the Constitution. That focus, however, fell with the 1957 anti-rightist campaign and disappeared during the Cultural Revolution.

“All the lawyers were labeled rightists at that time, and the whole judicial system was in chaos. It was very hard for any verdict to be based in law,” Zhu Jingwen, former standing deputy director of the Legislation Research Center under the China Law Society, told The Beijing News in a 2011 interview.

“The government’s focus did not shift back to legislation until the third plenary session of the Communist Party of China (CPC) 11th Central Committee [in 1978] decided to develop and improve its socialist legal system by working out necessary laws and strictly enforcing existing laws,” he added.

Crackdown on Crime

To quickly get China’s legal system back on track following the Cultural Revolution, Chinese lawmakers pushed through seven laws in three months, such as the long-awaited Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure Law.

Despite this, the crime rate increased steadily during the late 1970s and into the early 1980s. The long political campaign had shaken people’s faith in law and order. There were also large populations of restless, unemployed zhiqing, or sent-down urban youth, who as part of a mass campaign during the 1960s had been sent to work in the countryside – only to return to no jobs.

Public security authorities reportedly handled more than 2.3 million cases from 1980 to 1982. Around 180,000 involved serious crimes. During that period, cities saw a rise in gang-related activity, from looting and assault to rape and murder.

The tipping point came in 1983 with two massacres that shocked the nation. According to reports, Wang Zongfang and Wang Zongwei, two brothers and known gangsters, shot nine people dead and wounded nine after a failed robbery of a hospital in Shenyang, Liaoning Province.

Later that year, a group of eight men massacred 26 people in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, reportedly raping some of the female victims before the murders.

“We must crack down on serious crimes and penalize the criminals more quickly and heavily,” former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping said at a work conference in Beidaihe, near Beijing, in July 1983.

In response, the central government launched its Strike Hard Campaign one month later. While official data showed crime rates drastically reduced over the next two years, the campaign drew widespread criticism for its overzealous enforcement and police abuses.

The thrust of Strike Hard was against hooliganism, a nebulous charge that could range from mass fighting and disturbing public order to “group licentiousness.”

Some high-profile cases included 80s film star Chi Zhiqiang, who was given four years in prison for watching pornography and “cheek-to-cheek” dancing.

Another well-known case of being convicted of hooliganism is Niu Yuqiang, who was sentenced to death with a reprieve in 1983 for robbing someone of a hat, breaking windows and brawling. He was 18 at the time.

Niu was released on medical parole in 1990, but sent back to jail in 2004 to serve out the remainder of his sentence despite officials removing the crime of hooliganism from the books in 1997.

Dubbed “China’s last hooligan” by the media, Niu is set for release in 2020.

The draconian atmosphere of the Strike Hard Campaign is depicted in the film So Long, My Son (2019), where a character is arrested for attending a dance held with the lights turned off.

Powerful Connections

China’s reform and opening-up was in full swing in the late 1980s, which helped set the economic foundation for reinforcing the legal system. Lawmakers concentrated on drafting and instituting laws in the corporate, insurance and labor fields as well as general provisions for the Civil Law.

On October 1, 1990, China’s first Administrative Procedure Law went into effect, which granted citizens the right to sue officials. This unprecedented law soon became the focus of the country’s second five-year plan for popularizing law.

The Story of Qiu Ju (1992) from director Zhang Yimou captured the zeitgeist. It tells the story of the titular Qiu Ju, a pregnant woman from the countryside, who struggles for justice after village head Wang Shantang assaults her husband over a land dispute.

The movie, according to Zhang, not only encouraged the public to protect their civil rights, but also highlighted the contradictions of rule of law in a society that emphasizes connections and relationships.

Angered by Wang’s refusal to apologize for the assault, Qiu rejected the 200 yuan (US$30) compensation local police ordered Wang to pay and eventually takes her case to the city courts.

Qiu finds a lawyer and files a suit against Wang. But when the ruling finally comes down, Qiu would regret her efforts. Qiu had since given birth – and Wang was on hand to help her through a difficult delivery.

Wang had been sentenced to 15 days in detention. “Arrested? That’s not what I asked them to do,” Qiu murmured. The last scene shows a distraught Qiu chasing after the police taking Wang away.

“Qiu Ju was not seeking legal justice, but a sincere [face-saving] apology from the village head,” reads a user post on Douban, China’s most popular review website for music, movies and books. “That desire was fulfilled when the village head saved her... The movie highlighted the differences between ‘rule of man’ and ‘rule of law,’ replacing Qiu Ju’s forgiveness with a legal punishment. This shows how Chinese people had yet to realize that laws do not always satisfy personal emotions,” wrote the Douban user under the name “Mr Wayne.”

The comment touches upon a contradiction that Chinese law experts believe to be an obstacle to rule of law in China: connections.

Lack of support from villagers and Qiu’s husband about her persistent litigation also speaks to that point. Qiu even tells a local police officer that it was fine for the village head to beat villagers, as long as it did not result in serious injuries.

These contradictions were even more central to the 1994 movie The Accused Uncle Shan Gang. Though village Party Secretary Shan Gang skirts the law to settle disputes and carry out justice, the people believe he is acting in the greater interests of the village. The film highlights this point as villagers see off Shan in a show of support as local authorities finally detain him for abuses of power.

Faith in extrajudicial punishment, especially in remote villages, is partly a remnant of China’s feudalist past. Villagers often grant local leaders direct authority to punish those who harm the community’s interests. This sentiment not only makes it more difficult for the judicial system to deal with civil cases, but also emboldens people to take the law into their own hands.

Experts believe this may explain why some in China prefer petitioning to litigation. Separating the two while protecting legitimate interests and rights poses a long-term challenge for officials.

New Rules

A new step for China’s judicial system came in 1997 as rule of law was written into the work report of the CPC’s 15th National Congress, where the Party listed “building a rule-of-law State” as one of its objectives.

“When drafting the report, we had worried that rule of law would be replaced by ‘rule by law,’” Wang Jiafu, then a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences who helped draft the report, told Party newspaper People’s Daily in 2007. “Rule of law has a more extensive connotation, covering democracy, freedom and human rights, ideas that were not as widely accepted as they are now,” he added.

Xu Xianming echoed Wang and spoke highly of the central government adding “respecting and protecting human rights” to the Constitution in 2004. “Human rights are the focus of rule of law. It indicated that China has reached a new, higher level for rule of law,” he told the People’s Daily in the same report.

Thanks to the government’s emphasis on rule of law, the 2000s and 2010s saw increased efforts to eliminate extraction of confessions through torture, presumption of guilt and judicial corruption, as well as overturning unjust rulings. According to a 2017 report by the Supreme People’s Court on deepening judicial reform, from 2012 to 2017, courts corrected 37 major cases and acquitted 4,032 defendants.

The 2016 movie Innocence was based on the real case of Zhang Hui and his nephew Zhang Gaoping, both wrongly convicted of raping and killing a woman in 2003. The movie focused on their unjust trial and decade-long battle to prove their innocence with the help of their family and lawyer.

“The darkest aspects [of the case] were displayed, such as extorting confession by torture, ignoring evidence and poor supervision,” Zhang Biao, a prosecutor assigned to the case who was featured in the film, told the Procuratorate Daily. “Though not that in-depth, it was enough to make people think.”

The movie revealed the progress made in China’s judicial construction following Chinese President Xi Jinping’s 2014 campaign to promote rule of law in “an all-round way” and deepen judicial reform at a time when such topics would have been taboo just a few years earlier, the article read.

Qiu Ju argues with village head Wang Shantang in The Story of Qiu Ju

A juror argues with jury foreman Lu Gang in 12 Citizens

Village head Shan Gang in The Accused Uncle Shan Gang

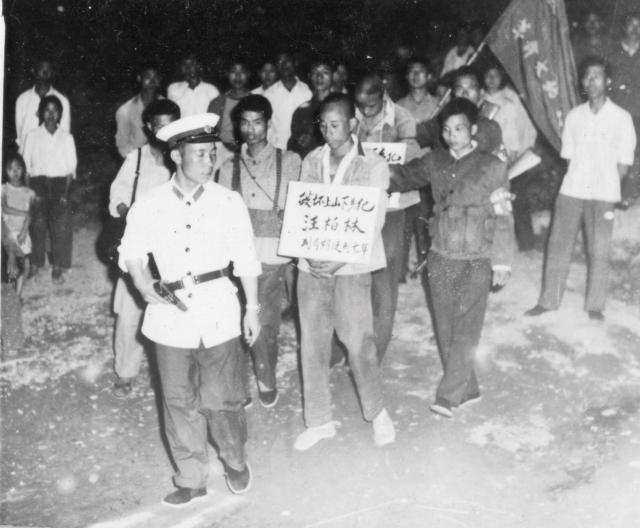

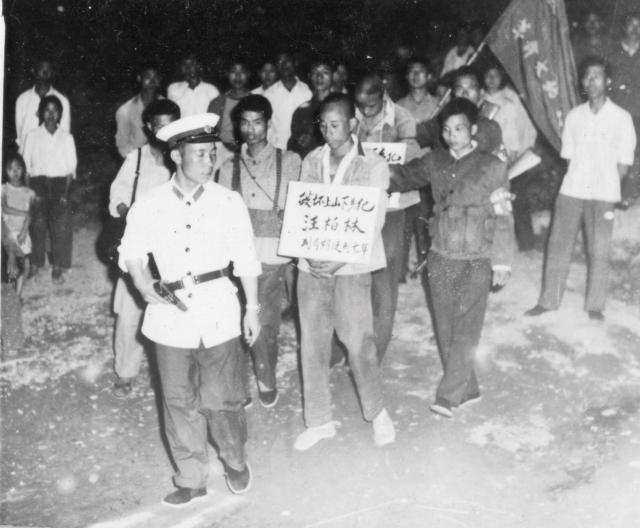

A struggle session during the Cultural Revolution in 1975

Eighteen suspects are arrested for robbery, theft and scalping train tickets and paraded at Beijing West Railway Station, June 14, 1996

Lin Mengmeng’s father Lin Tai is restrained in court in the movie Silent Witness

A still from the movie Innocence

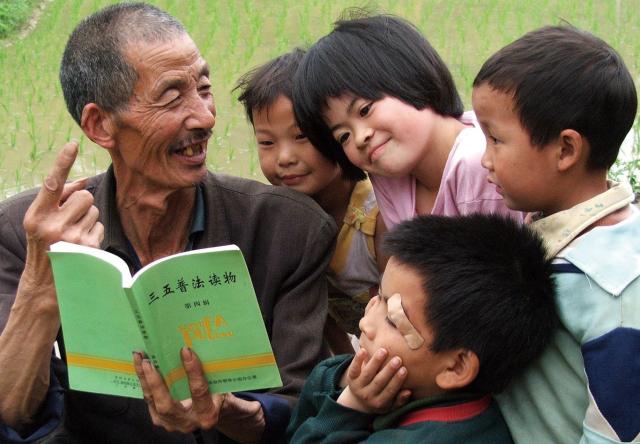

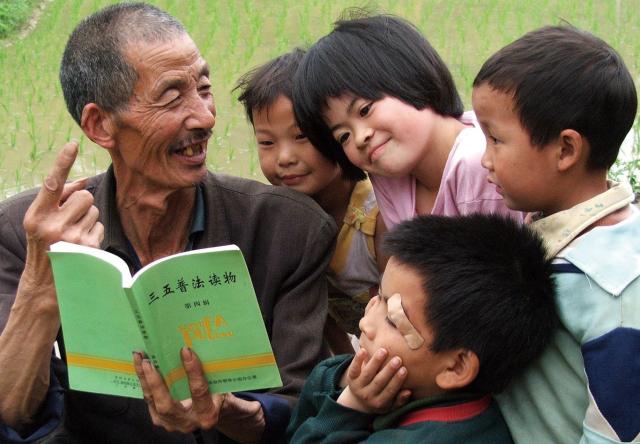

Jiang Xinchun, a village head in Shaoyang County, Hunan Province, talks about the law with left-behind children, May 10, 2006

Law graduates from Yunnan Normal University hold a mock trial at the Provincial Supreme People’s Court of Yunnan Province for their graduation oral examination, May 4, 2017

Public Perceptions

Public opinion has also played an important role in China’s judicial progress over the past 20 years, especially after the rise of Weibo, WeChat and other social media. However, public sentiment is also vulnerable to distortion.

The 2013 courtroom thriller Silent Witness explores this issue through the fictional case of Lin Mengmeng, a young woman accused of killing her father’s girlfriend after a heated argument. To save Mengmeng from prison, her father, financial tycoon Lin Tai, hires a high-powered law firm that works to manipulate public opinion of the case in their favor.

“We must use the power of the public and trigger their sympathy for Mengmeng... Pay writers to talk about the case and highlight that Mengmeng was a child with a single parent,” says their defense lawyer Zhou Li.

“Public sentiment is our means of defense. Remember, the public is always kind-hearted,” Zhou tells her team.

The film recalls the heated atmosphere surrounding the case of Tang Hui, a mother in Yongzhou, Hunan Province, who sought justice for the rape and forced prostitution of her 11-year-old daughter.

According to Tang, her child was abducted in 2006. After an underwhelming response from local police, Tang desperately continued her search. The child was eventually spotted at an underground brothel. Tang and two relatives rescued her – without the help of law enforcement. Her plea for justice struck a chord with the public, which pressured law enforcement and courts to further investigate the case. Tang repeatedly made public appeals, such as kneeling in front of local government buildings and petitioning in Beijing, where she called for the death penalty for all seven suspects in the crime.

However, some members of the public and law experts criticized Tang’s tactics, accusing her of interfering in the judicial process by taking advantage of the public’s kindness. Tang was arrested and spent a week in a labor camp in 2012 for her persistent petitioning. Her story drew such an outpouring of public support that she was later released and compensated in a landmark court decision.

Tang’s case remains an important case study of the influence public sentiment has on the judicial process.

This is also a main theme of the 2015 film 12 Citizens. Heavily based on the 1957 American film 12 Angry Men, the crime drama uses a mock murder trial to probe how each juror’s personal feelings and biases influence their decisions while emphasizing the importance of evidence-based convictions.

The film is now seen as foreshadowing a change to China’s jury system. The same year, China piloted reforms in 10 municipalities and provinces that further defined the selection, roles and duties of jurors, officially referred to as assessors. Experts said the move helped improve public perceptions of the rule of law.

“Introducing assessors to the judicial system helps root judges’ rulings closer to everyday life while enabling people to better know, understand and accept the judicial process,” Tang Chudong, a law professor at Hunan-based Central South University, told Guangming Daily in 2018.

China issued the People’s Assessors Law in 2018, which formalized the system for the first time in the country’s history. The Supreme People’s Court called the move an important part of “socialist rule of law with Chinese characteristics.”

“It isn’t nitpicking for details when a young man’s life hangs in the balance,” said Lu Gang, the jury foreman in 12 Citizens, a line that seems a world away from the countryside justice of Hibiscus Town. “It’s a reflection whether a country’s laws are just.”

Old Version

Old Version