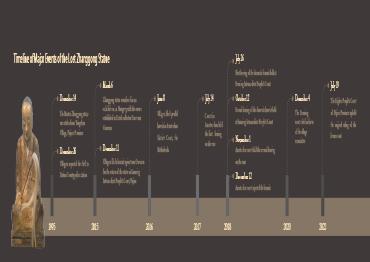

Despite van Overeem initially denying that his was the statue in question, evidence quickly piled up: Archival materials, old photos and documents pointed to the Zhanggong statue.

Through both official and private channels, people from Yangchun and Dongpu began to negotiate with van Overeem for the statue’s return. According to one Yangchun resident involved in the recovery efforts, van Overeem asked for US$20 million, but he wanted the statue to go to Nanputuo, a larger and well-known Buddhist temple in the metropolis of Xiamen, around 200 kilometers south of Yangchun. “We couldn’t afford that much money. More importantly, he bought the statue in Hong Kong for 40,000 Dutch guilders (around US$20,000) in 1996, which was illegal,” added the villager, who requested anonymity.

When negotiations failed, villagers turned to the courts. With the help of a pro bono legal team, Yangchun and Dongpu village committees filed a joint lawsuit against van Overeem in Sanming, Fujian in 2015 and in Amsterdam the following year.

“Since many of the issues involved in this case have no precedent, such as legal application, relationship and facts, as well as technical issues of evidence review, we’ve had to research and verify our findings while filing lawsuits simultaneously in two countries,” Xu Huajie, a lawyer with Beijing Jingshi Law Firm who acted as lead counsel in the case, said in a September 2023 interview with NewsChina.

“In the Amsterdam lawsuit, we argued that Dutch law states ‘a person is not allowed to have the corpse of an identifiable person in their possession,’ and in China we argued on the grounds of property rights,” Xu said.

Six villagers, including Lin Yongtuan and Lin Kaiwang, traveled to Amsterdam in late October 2018 to attend the second hearing. Van Overeem told the court that he bought the statue in 1996, but could not provide documentation as to its source. He claimed to have since traded the statue with another collector in 2015, and refused to reveal their identity.

Dutch lawyer Jan Holthuis, who represented the villagers in Amsterdam, argued that “such an agreement is contrary to good morals, and is an affront to decency and public order, therefore is void,” the Xinhua News Agency reported.

However, an Amsterdam district court ultimately dismissed the lawsuit in 2018, finding the two Chinese village committees “not legal entities and therefore ineligible to file a claim.”

Things went more favorably in China. After two hearings, Sanming Intermediate People’s Court ruled in 2020 that the village committees retained ownership and demanded the statue’s return.

In its decision, the court cited two international conventions on the illegal trade of cultural relics: the UNESCO 1970 Convention, to which China and the Netherlands are signatories, and the UNIDROIT Convention of 1995, which the Netherlands has yet to ratify.

“As both those conventions are devoted to prohibiting the illicit trafficking of cultural property and facilitating the return of cultural property to their original nations, the court concluded that it should interpret the lex rex sitae [law from where the property was first situated],” wrote Huo Zhengxin, law professor at the China University of Political Science and Law in an online article published in late 2020 by China Justice Observer under the by Academy of Comprehensive Rule of Law at China University of Political Science and Law.

The court also referenced China’s Property Law, under which acquisition in good faith does not apply to stolen cultural property.

Van Overeem appealed to the Fujian Provincial High People’s court, which upheld the ruling in July 2022. Villagers celebrated the decision with fireworks and sacrifices to the replica statue in Puzhaotang Hall.

Old Version

Old Version