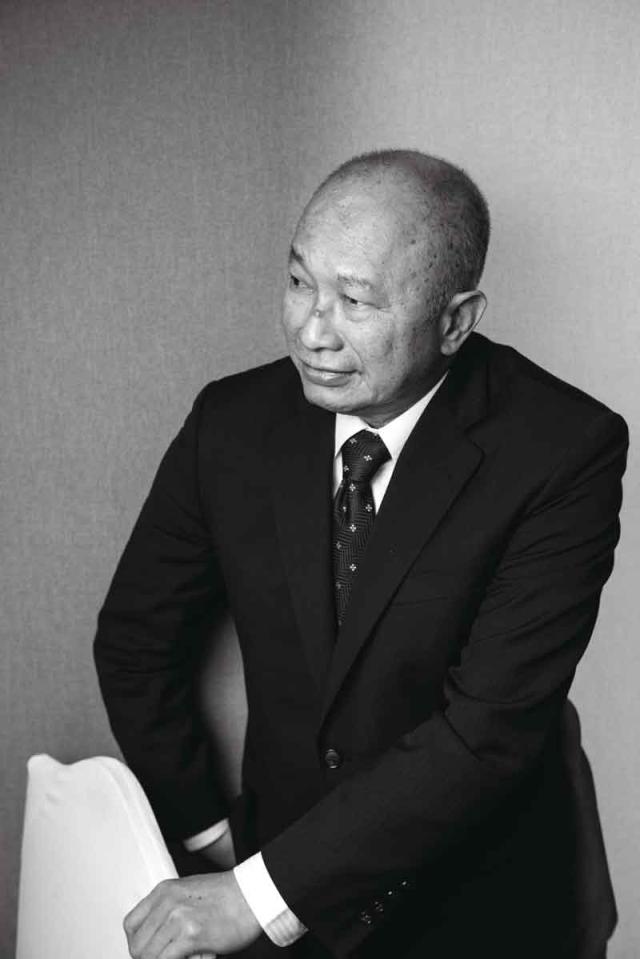

If Woo’s personal experience were filmed, it would be a perfect inspirational biopic. James Wong, regarded as one of Hong Kong’s finest lyricists, has worked with Woo many times. The preface of Woo’s biography, written by Wong, states that the first half of Woo’s life was representative in Hong Kong as a typical example of a rags-to-riches story.

Born in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, Woo moved to Hong Kong in 1950. He was five. A young Woo dreamed of being a hero but struggled after his father died of tuberculosis, and then growing up in a crime-ridden slum surrounded by violence and social upheaval. He reflects that in those days, he would take either a club or a brick with him whenever he went out in the evening.

On October 10, 1956, violence broke out between pro-Nationalist and pro-Communist factions in Hong Kong, resulting in 59 deaths and hundreds of injuries. It left an indelible imprint on Woo’s mind. “Some people placed bombs in the street, injuring many people. I saw people beaten to death with my own eyes,” he told NewsChina.

Woo said these horrific scenes significantly influenced his future work, including the recurrent chaotic action sequences, deadly standoffs and blood-soaked heroism that permeate his works.

His personal take on violence debuted in his first film in 1973, when a 26-year-old Woo became Hong Kong’s youngest ever film director. But the movie was banned because it featured scenes in which the villain fought with a nailed glove. Two years later, the film was recut by the famed Golden Harvest Studio and was released with the name The Young Dragons, marking the start of Woo’s 10-year collaboration with the studio.

At the beginning, Woo directed a series of comedies requested by the studio, such as Hand of Death and Money Crazy. In 1979, Woo wrote, produced and directed the martial arts film Last Hurrah for Chivalry, which was deemed a precursor to Woo’s later works.

But the film was not a financial success and Woo returned to comedies. It was a crucial moment of transformation in Hong Kong in the early 1980s, and the public was curious about the city’s future at a time when the British and Chinese government were negotiating the handover of the territory. In 1982, Woo produced Plain Jane to the Rescue, a comedy that dealt with themes of great social change.

“I am probably the first director to shoot a film about the transference of sovereignty over Hong Kong,” he said. The film grossed HK$5 million (US$650,000) at the box office, despite being regarded by movie critics as “wild dreams of the highly-educated, who know little of the hardships of the average people.”

In the mid-1980s, Woo experienced a creative bottleneck. Several of his movies were financial losses. Wu’s luck finally turned in 1986 when he started to collaborate with Tsui Hark, a master of Asian cinematography. Together they produced the blockbuster A Better Tomorrow, which was acclaimed as one of the best works of Woo’s early years as a director. Next, they made several blockbusters including A Better Tomorrow II and The Killer.

All his movies in this golden period featured Woo’s patented action elements: combining violence and aesthetics, gunplay in churches, slow motion, setting the tone of his style and also arousing the attention of international critics. Woo is seen as the forerunner of so-called “gun fu,” an action film genre that combines dazzling gun play with Chinese kung fu.

Artistic differences saw the two eventually part ways. In 2015, Woo invited Hark to edit the second half of the film The Crossing, after the box office failure of the movie’s first half, which was released in 2014. Featuring an all-star cast, the four-hour epic has been described as China’s Titanic.

Old Version

Old Version