Old Version

Old Version

In the dead of night, during a plum rain storm that brought the torrents cascading down from the hills around Taichung in laminate-layer waves, the pine tree cracked and collapsed into the pond.

As we trudged out onto the deck in response to the 4am wake-up gong, we hardly noticed the change, still dark as it was on the water and the swathe of wild garden beyond. It was only on returning to the dormitories before breakfast that one by one, we picked up the smell of wet needles hanging heavy in the air, like dust from a beaten carpet, and put two and two together.

No doubt each of the dozen or so men in the dorm reflected on the dramatic change and drew parallels with the philosophy of vipassana meditation we were there to learn, though as we were strictly forbidden to speak, it would be another few days before I’d have a chance to check.

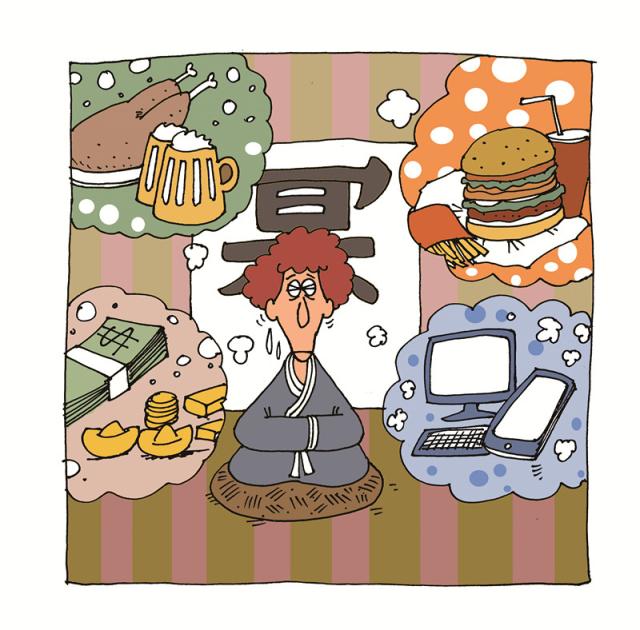

Vipassana was developed, like Buddhism, in India over 2,000 years ago, but the Chinese tradition has been strong ever since Buddhism arrived in the country. Literally, it means “to see things as they are.” The collapsed tree poignantly illustrated vipassana’s fundamental tenet: that all things are mutable, and therefore really not worth craving or averting. This may seem obvious, but the key with vipassana is that you spend more than six hours a day meditating on the fact, while attempting to remain indifferent to the alternating sensations of pain and euphoria that course through your body. The ability to remain unperturbed in the face of leg-deadening cramp or spasming back pain, as well as full-body sensations akin to an uplifting acid trip, is supposed to stand you in good stead when faced with real world challenges and temptations.

I found the experience both profound, and profoundly boring. Like most of us, I’ve got used to the endless blitz of media through my phone and other electronics. Imagine if you picture removing all the stimulus from your life and giving your mind 10 days to dwell on it. Handing over your phone and close possessions, and signing what amounts to a contract with yourself not to leave before the 10 days are up, is nothing short of terrifying. From the moment the lights go out on the evening of the initial day, you are on your own.

Which it turns out is not so bad, at least for those attending on this occasion. The teacher, who was communing from beyond the grave via VHS-quality video, pointed out early on that the weak-minded usually find an excuse to bail on day two or six. It was on the latter date that I felt the strongest urge to get the hell out, deep into the nothing and with a considerable time still to go before I could break surface. I got over it, and am extremely pleased I did.

It’s easy for foreigners living in an alien culture like China to become irritable and grumpy, just as with Chinese who face culture clashes abroad. Taiwan isn’t as noisy as the Chinese mainland, but it’s still a bustling place, and it’s hard to find spots of silence inside it. But as the days passed, we were progressively taught a meditative technique that I expect will prove useful for the rest of my life. On emerging from the course, the sensation was like having a car alarm I was barely aware of suddenly fall into silence. That background hum our digital and urban lives too often instills in the recess of our minds was gone. I could think clearly, about one thing, for as long as I wanted. Being off the booze and solely eating vegetarian food may have helped as well, but it was still remarkable.

And yes, I was skeptical about the potentially cultish implications of being slowly hypnotized by the practice. But it’s entirely free, and only students who complete the course are asked for a donation.

Perhaps the most startling and revealing aspect of the practice came early on. We were asked to mediate on our breath as it passes in and out of the nose. Simply to observe the breath’s passage. My sheer inability to do this for more than three breathes was telling. But as the days went on, the sharp-tugging waves of intrusive thought began to recede into whispers, passing me back control of the immediate moment.

In that immediacy, the deliberately natural setting of the retreat complex came to the fore. Ants marched incessantly, insects cocooned in webs, fish snatched in a flash of vermillion kingfisher wings, frogs performed a mating chorus so deafening earplugs were required for sleep.

It was nice to have so much time to observe and reflect on such things – and people. Sitting in silence, I told stories about my fellow classmates to myself – only to learn afterward most of my conceptions had been wrong. Silence is a great teacher, especially in a noisy country.