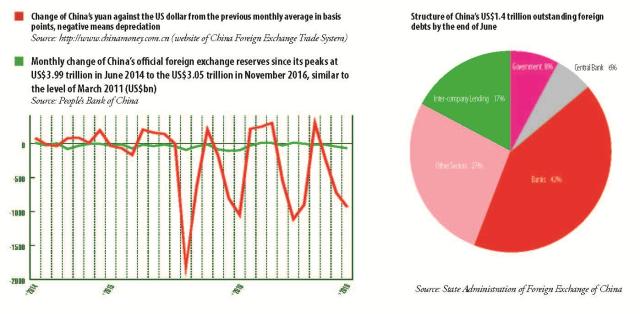

However, over the past two years the central bank has had to respond to events not only with these arguments, but also with actions to defend the yuan’s value against the US dollar. These efforts show that the central bank does not think there is nothing worth worrying about. China’s foreign exchange reserve has dwindled by US$800 billion from its peak of almost $4 trillion in June 2014. The central bank’s explanation that it reflected the growing investment of Chinese companies and spending of Chinese tourists on the overseas markets has done little to convince market players and observers, who believed it was partly caused by the central bank’s selling of US dollars to defend the yuan and serious capital flight.

The control of capital outflow has been tightened. As of the end of October, China UnionPay card holders were banned from buying certain insurance products in Hong Kong, notably life insurance, which are also used as investment and deposit tools. Before that, many rich Chinese bought such policies to shift their capital out of the Chinese mainland. On November 28 and December 6, more stringent scrutiny on overseas investment projects were declared jointly by the four ministries supervising China’s overseas investment and foreign exchange, including the Ministry of Commerce, the PBOC, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange and the National Development and Reform Commission. These measures are intended to block the ways that investors get around capital control to transfer their assets under the cover of consumption or investment.

There is a consensus among analysts that the depreciation over the past two years, even the accelerating depreciation of the past two months, may not yet be a big problem, but the very lingering expectation of further, continued depreciation may in itself lead to excessive depreciation one day. As Sheng Songcheng, a senior advisor to the PBOC, said at a forum sponsored by Caixin Media in Beijing on December 3, that expectation is often self-reinforced and self-fulfilled, which, in the case of depreciation, undermines confidence in a currency and, in turn, can lead to disastrous consequences. There are even debates on whether China should slow down the pace of the yuan’s internationalization and instead make yuan stability the top priority.

In addition, most of China’s short-term foreign debts are on the books of China’s private sector. The yuan’s devaluation itself has already added to the burden of those debtors, and the yuan’s devaluation would motivate them to convert some of their yuan holdings into US dollars to repay their debts quickly, before the due day. This situation, Sheng noted, means further drainage of China’s foreign exchange reserves. Chinese citizens are allowed to convert the equivalent in yuan of US$50,000 a year. With the new year coming, people may rush to use up their annual quota at the beginning of the year for fear of further devaluation.

If the yuan suffers excessive depreciation, China’s central bank will, theoretically, have to either burn through a lot of the country’s foreign exchange reserves, or increase the interest rate to attract capital back to China, or both. The foreign exchange reserves are not without limit, and were not easily accumulated in the first place. If a country uses the interest rate tool to alter its exchange rate, the reduced independence of that country’s monetary policy may hurt its economy. In China’s case, a sharp interest rate increase could burst asset bubbles, arguably in the housing sector, and drag the whole economy into recession. A too cheap yuan would also make China’s imports more expensive, pushing up inflation. This risk has already begun to appear in the recent soaring of international commodity prices. Worse still, in economic history, the excessive and sudden depreciation of a currency against the US dollar has often proved to be a precursor to a sweeping financial crisis for the country issuing the currency. Though China’s total foreign debts are not too large, crises in other emerging economies would have a spillover effect on China.

How Free?

Analysts are calling for expectations for the yuan to be stabilized before the new year. Part of the solution lies in how the yuan’s exchange rate system itself can be adjusted. They agree that capital controls should be tightened, but are not united on the issue of whether to let the exchange rate float freely. There is a stronger voice than ever calling for more flexibility. Some suggested that the existing two percent cap above and below the parity price be eased to allow more fluctuation of the yuan’s exchange rate on the daily spot market.

The recurrent devaluation of the yuan and the persistent expectation for further devaluation over the past two years show that the central bank is choosing to let the yuan devalue gradually. Professor Yu Yongding of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences is a firm advocate of going as far as putting the exchange rate fully in the hands of the market, on the condition that capital controls are kept. Controlling the pace of depreciation via intervention in the parity price and the limit of the fluctuation band, he argues, would just extend the expectation of further depreciation for a longer time, and thus provide more incentives for capital outflow. By contrast, once an immediate depreciation without intervention stabilizes the yuan’s value, the more expensive US dollar against the yuan would then discourage capital outflow. This way, China’s monetary policy can be more independent from the yuan’s exchange rate; China’s hard-won foreign exchange reserves can be kept intact, and strict capital controls, which are costly and difficult, would be easier to manage and less stringent.

Yu also dismissed the fear that the yuan would suffer a free fall of as much as 20 to 25 percent in such an action. He argued that this has never happened to an economy with the world’s largest official foreign exchange reserves, a trade surplus, much faster economic growth than the world average and a higher yield of financial assets than the US. The period before Donald Trump takes office in January 2017, when he will have the chance to implement his expansionary fiscal policy is the window for China to do this, Yu and his colleague Xiao Lisheng wrote in an article for Shanghai Securities News on November 22.

No one knows what the relatively stable level of the rate, or the so-called equilibrium exchange rate, would be. This is why some believe stronger, not weaker intervention is necessary. Sheng Songcheng has seen little reason to believe the market would automatically get back on the right tracks after what he sees as an irrational derailing of the yuan’s value when China’s economic and financial situation is sound. He personally advised the use of some foreign exchange reserves or an increase in the interest rate to prop up the yuan now, and was concerned that delaying will require more ammunition.

Urgent Action

The expectation of the movement of the yuan is based not only on the expectation of the US interest rate policy, which China cannot do anything about, but also on the expectation of affairs within China. When it comes to the expectation of the yuan for the long term, the latter is a bigger factor than the former. This is why the “economic fundamentals” have always been regarded by policy makers, investors and analysts as the solution for building positive expectations for the yuan, though they may not be the problem causing the current heavy downward pressure on the yuan.

There are at least two main relevant long-term issues of expectation to be addressed when it comes to propping up the yuan’s prospects. While Chinese private companies are making more investments in overseas markets, their shrinking investment on the home market has sent an alarming signal for domestic growth. In the first 10 months of 2016, China’s private sector only spent 2.9 percent more than they did during the same period in 2015 on fixed asset investment, compared with an 8.3 percent rise of the total fixed asset investment in China by all investors, including state owned enterprises and foreign firms. Chinese buyers’ insatiable appetite for houses in overseas markets has continued. The growing demand for and capability of diversifying their assets, as increasingly affluent populations always have, can only explain part of the reason.

On November 28, the CPC Central Committee and the State Council published a decision on the protection of property rights. It states clearly that the purpose is to consolidate the public’s sense of security towards their wealth and assets. It pledges to grant “equal protection” to both public and private property. To achieve this, rules and laws based on ownership will be annulled, and past and present cases involving infringements of private property rights will be reviewed. These commitments immediately attracted wide attention. The discriminatory treatment towards private property has caused “anxiety” among some entrepreneurs, who were “unwilling to invest [in the domestic market] and transferred their assets outside,” writes an editorial of the Party’s mouthpiece People’s Daily on December 5. It also claimed that a number of wrongful court rulings would be identified and corrected to prove the resolution on property protection.

Indeed, the discontent surrounding the implementation of reform policies has been one of the major concerns for China’s economic prospects. Liu Shijin, vice director of the China Development Research Foundation, noted that it is this expectation that lies behind the yuan’s exchange rate fluctuation and declining private investment.

Stabilizing the expectation for the growth, he stressed, cannot be achieved by setting a high growth target, but “stabilizing the expectations around the implementation of the reform,” he said at the Caixin forum on December 3. The same day, Xu Jinghong, chairman of Tsinghua Holdings which invests in innovative start-ups, also said at a forum in Hainan held by Xinhua’s sike.news.cn site, that private companies have money, but transfer it overseas due to a lack of a sense of safety. Reform measures announced in the past few years are “all in the right direction, but many have not been implemented,” he added.

Expectation is virtual, but it is built on reality.

Old Version

Old Version