Fu Chen felt disheartened on hearing the news of the death of one Chinese soldier and wounding of another four in a terrorist attack in Mali on June 1. The victims were members of a UN Peacekeeping Force, and the soldier who died was only 29 years old. Fu Chen thought back to three years previously, when he was stationed in Mali during his time with the French Foreign Legion (FFL).

Fu’s experiences in the desert are seared into his memory, particularly the dazzling sun reflecting off tanks and assault rifles. “When I heard the news [of the attack] I felt miserable and lost for words.”

In recent years, a rising number of Chinese nationals have joined military forces in other countries, finding themselves stationed and even experiencing combat in war-torn areas including Mali, Afghanistan, Iraq and Angola.

Motivations

If it hadn’t been for a personal tragedy that took place in 2007, Fu Chen’s life would likely have followed a script familiar to most Chinese of his generation: a stable office job, marriage, and then a child.

That year, Fu’s girlfriend was murdered, with the chief suspect an ex-boyfriend who disappeared soon after the crime. The incident shattered Fu’s life and left him unable to focus on work. He sank into depression.

One day, he came across an article about the French Foreign Legion, a branch of the French army commanded by French officers but composed of volunteers from around the world. “To join a mercenary legion meant saying farewell to my old life,” Fu told our reporter.

The legion was formed by Louis Philippe, the last French King, in March 1831 as a colonial expeditionary force designed to defend and expand France’s overseas holdings and eliminate insurgent threats. The force went on to fight in almost all of France’s wars, and in defense of French interests. In the past two decades, the legion has been deployed in Bosnia, Cambodia, Chad, Congo, Iraq, Ivory Coast, Kosovo, Kuwait, Rwanda and Somalia. Most recently, legionnaires fought in Afghanistan as members of the French contingent.

Unlike a regular army force, the foreign legion does not enquire about the history and origins of its recruits, allowing them to enlist under an assumed identity, earning the force a reputation as a refuge for fugitive criminals and those seeking an escape from their personal history, their true identities protected by the Legion.

After completing a five-year contract of service, soldiers in the Legion can apply for French citizenship, also making service in the Legion an option for would-be immigrants. According to reports from domestic media, by the 1990s, a total of 300 Chinese nationals had joined the legion, which comprises some 7,000 soldiers from around 150 countries.

In 2010 Fu Chen finally arrived in France. After physical exams, a face-to-face interview, a written test, and four-month boot camp, he became a soldier in the 1st Foreign Cavalry Regiment. In the first few months after joining the armored cavalry, Fu’s training regimen was even more tedious and exhausting than boot camp. From weapons drills and long marches weighed down with heavy packs, to farm work, soldiers were required to meet extremely high physical standards and endure verbal and physical abuse from their commanding officers.

“Despite having made mental preparations for all these tortures, when I experienced them for real, they went far beyond what I had imagined,” Fu told NewsChina. “When I was forced by one officer to clean a toilet with my own toothbrush, I couldn’t help wondering why I’d joined up.” According to Fu, many soldiers washed out during training, but he persisted, though he admitted weeping the first time he called his mother from the base. He also discovered that mental and physical exhaustion helped him forget his depression. “The reasons why a soldier joins the Legion will determine whether he sees it through,” he explained.

Chen Yong, 27, also serving in the foreign legion, gave a similar assessment to Fu’s. Now serving as a paratrooper, this high school dropout told NewsChina he would have once referred to himself as a “bad boy.” In 2015, he arrived in France and went straight from the airport to the foreign legion recruitment office. From then on, he had a new name and identity.

Chen explained his decision to join the Legion as “atonement for his previous life.” Chen refused to elaborate on the circumstances of his departure from his native Guangdong Province. His family do not know about the precise nature of his work in France, and Chen allows them to go on believing he is an illegal migrant worker.

For many legionnaires, permanent residency and French citizenship are reasons enough to enlist. However, those seeking to be soldiers of fortune are likely to be disappointed. The monthly salary ranges from 1,000 to 2,000 euros depending on which division one serves in, only slightly above the minimum wage in France. Among the 40 some new recruits who enlisted last year, Chen Yong was one of four Chinese nationals. Of the remaining three, two were seeking French citizenship, while one, a Chinese overseas student in the US, was, Chen told our reporter, seeking a “different way of life to enrich his experiences.”

Chen Yong commented that he stood apart from his three compatriots. “I came to experience a life of hell. I wanted to suffer in misery.”

Battlefield In March 2012, during the military coup in Mali, religious extremists and anti-government insurgents occupied the northern part of the country. As Mali’s previous colonial ruler, France deployed military assets in support of local forces fighting the insurgency in early 2013. The French Foreign Legion was a major part of the French commitment.

Fu Chen was deployed to Mali in May that year. His major responsibility as an armored vehicle driver was reconnaissance. For the first time in his life, he witnessed real war. In the small town where his regiment was billeted, Fu saw bombed-out schools, their blood-spattered walls peppered with bullet holes, math equations still scribbled on cracked chalkboards.

During his four-month deployment, Fu faced threats from both anti-government forces as well as the harsh climate. Excruciating heat, venomous snakes, scorpions and mosquitoes are a part of life in the Sahara Desert, and Fu contended with them all while fighting the insurgency. The scarcity of water meant he had to shower in a mere 1.5 liters of it.

Fu described how, one day, on a routine pass through a local town, passersby stopped on the street to stare at his detachment. Children, he said, jumped with joy and some adults even shed tears. He related how one elderly man who had lost a leg in the fighting raised one arm in a salute. “The moment was unforgettable,” Fu Chen said, adding that such incidents made him feel proud and reassured him that he was fighting a just war. “We were doing things that were righteous.”

Despite the sense of purpose he sometimes felt on the battlefield, the experience of those serving in the legion is characterized by monotony and backbreaking labor. “Most of the time,” Fu told NewsChina, “it was a prison-like environment.”

For some recruits, the experience is far from rewarding. In 2010, before a foreign legion infantry division was due to be dispatched to Afghanistan, eight Chinese soldiers asked to be relieved from duty, allegedly reluctant to risk their lives. The case resulted in a backlash from the Foreign Legion command HQ, which promptly cut recruitment of Chinese nationals.

For some recruits, the allure of French citizenship is not worth risking the dangers and privations of war.

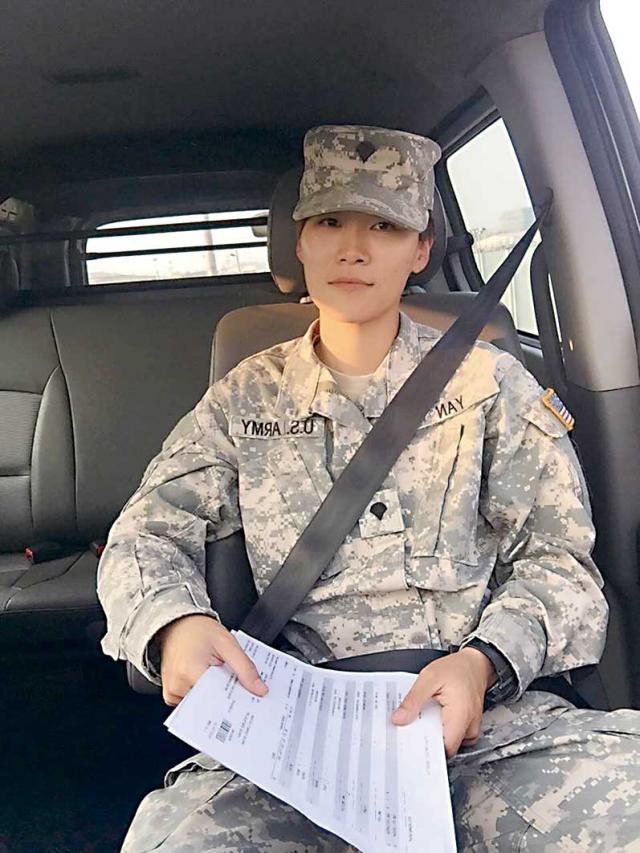

Dream Others have more romantic motivations for enlisting. In 2009, Yan Qian’s parents sent their daughter to study at a community college in the US. However, a persistent language barrier and general loneliness left her feeling isolated there. Three years later, in late 2012, she walked into a US Army recruiting station in her local Chinatown. In her eyes, to serve in the army seemed to be, as she puts it, a “not bad opportunity” to gain life experience, improve her English, develop a social circle, and, more importantly, realize her childhood dream of being a soldier. Yan’s parents supported her decision once her recruiting officer informed her that, as a woman, she would not be given a combat role.

A keen basketball player, Yan was physically fit and was soon recruited into a battalion of 16 female soldiers, of whom she was the only one of Chinese origin. She went on to train as a driver, and was surprised to find herself deployed to a frontline role in Afghanistan in 2014, charged with transporting and guarding weapons convoys.

In Afghanistan, Yan was often ordered to drive at the head of weapon convoys, making her responsible for identifying and removing roadside bombs. Yan Qian experienced bomb attacks, ambushes, and targeted Taliban raids. She remembered being drenched in cold sweat the first time she dealt with an explosive device, though, she continued, she gradually became accustomed to danger. Her battalion, well-armed and equipped, suffered few injuries. “As long as I stayed in my vehicle, I was safe,” she told our reporter.

In recent years, in response to a US recruitment drive by Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest (MAVNI), increasing numbers of Chinese students like Yan have enlisted in the US army as a fast-track option for citizenship. While Yan may have cared more about obtaining a stable job and enriching her life experience, for many, the prospect of citizenship, as with foreign recruits to the FFL, is the most appealing aspect of service.

Since returning from Afghanistan, Yan Qian has suffered repetitive nightmares. “I’m under attack, and I find the weapon I’m holding isn’t loaded.” On waking, she said, she immediately reaches for her gun. Despite this, in 2015, Yan Qian renewed her contract with the US Army, stationed in South Korea when NewsChina talked to her, and expected to be deployed to the Middle East this September.

Mental distress is a problem Chinese nationals serving in foreign military forces deal with on a regular basis. Fu Chen remembered how a soldier from the Netherlands began to use broken glass to self-harm before quitting. Fu and a few squad mates decided to rent an apartment in Marseille to try to experience a normal life, buying fresh produce at the market and cooking for one another. He spent his leave backpacking around France. When his contract was completed in June 2015, he decided not to renew it. He now plans to start his own private security firm in France.

Chen Yong has just served the first year of his contract with the legion, and he admits that living under a new identity is “a very weird feeling.”

“I thought I could confess and make amends through hard labor in the army,” Chen continued. “But now I will still have to face and solve all my problems.”

Old Version

Old Version