“Publishing and studying The Plum in the Golden Vase is risky. It is a very special branch and you might go wrong if you are not careful enough,” Wang told NewsChina, revealing that in the early 1980s, a publishing house in Shaanxi Province was punished for publishing a comic strip of The Plum in the Golden Vase without permission, and someone in Sichuan Province was penalized for illegally reprinting a Cihua edition of the novel obtained from Hong Kong.

In 1988, soldier-writer Han Yingshan rewrote a shortened edition of The Plum in the Golden Vase and printed a first run of 300,000 volumes. His book was soon banned, however, triggering protests from academics. “I support cracking down on pornographic books, but we have to clearly define what pornography is,” Cong Weixi, then editor-in-chief of the China Writers’ Publishing House which published Han’s book, reportedly wrote to the State Administration of Press. “It is narrow-minded that we, a country with 1.08 billion people, banned the [classic novel] of The Plum in the Golden Vase … and it is even morbid that we regard Han’s book, a rewritten The Plum in the Golden Vase with sexual description deleted, harmful,” he added.

An editor of the PLPH who did not wish to reveal his name told NewsChina that the department held a meeting to discuss Han’s book and finally decided to uphold the ban of the book but not to keep pressuring the author.

It seemed that people’s protests did nothing to ease the sensitivity around the classic novel whose label as “pornography” was proving hard to remove. In the 1980s, as the four great Chinese classic novels were all adapted into TV series or movies, applications from several provinces to film The Plum in the Golden Vase were all refused. In the 1990s, Chinese director Chen Jialin managed to get a permit to film the novel, but as he was about to shoot, a notice suddenly arrived, ordering him to stop the movie and return the permit.

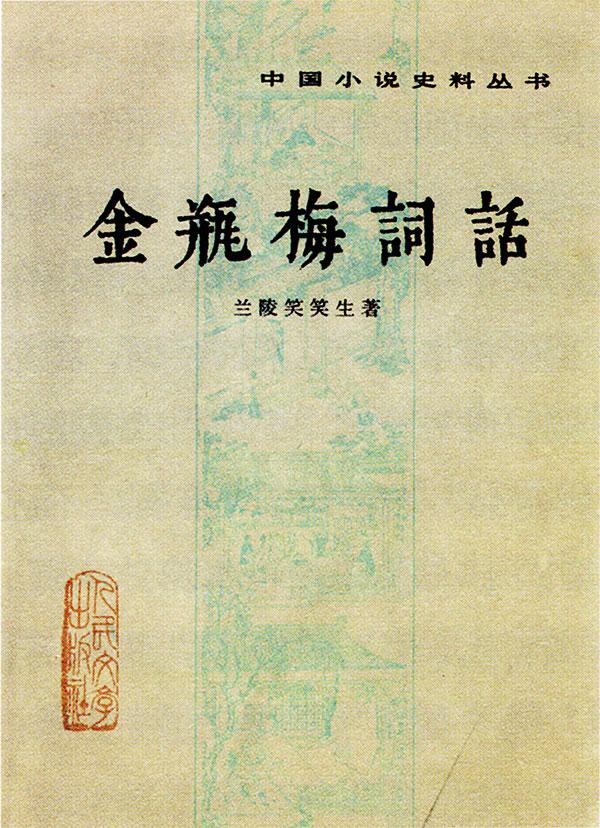

The academics, however, kept petitioning to reprint the unabridged editions of the novel. In 1988, both Peking University and the Qilu Press received approval to publish an unexpurgated Cihua edition of the novel, with the printing under strict supervision of the police, so strict that a Taiwanese paper mocked the situation as being as tight as the printing of the gaokao papers (China’s annual national college entrance exam).

Although the buyers were once again restricted to those who held a title above deputy professor, the 8,000 copies of the edition reportedly sold out within three months. When Qilu Press applied for a reprint, the State Administration of Press (then a new department after the former State Press Bureau was disbanded) refused, claiming that 8,000 volumes were enough for academic study and it would harm minors and young people if the edition were leaked among the public.

A Mirror of Today

The academics did not give up. In 1995, Chinese Qing dynasty historian Bu Jian and linguist Bai Weiguo received permission to make a new abridged Cihua edition with detailed annotation about the unfamiliar terms and old slang found in The Plum in the Golden Vase, which was believed to be of great use to help readers understand the content and themes of the novel.

Roy did the same thing. He added over 4,400 endnotes to the translation he did of a copy he picked up in a second hand bookstore in Nanjing in 1950, which even Chinese scholars praised as a “reference book.” Zhang Yihong, a visiting scholar at the University of Pittsburgh told the New York Times that Roy’s translation “opens a window onto Chinese literature and culture.”

In 2002, Bu Jian and Bai Weiguo applied to make a new annotated edition of the novel based on the Cihua edition. This time, they decided to restore the formerly deleted words. “The sexual description is also a part of the novel, and the deletion will make the novel less readable and its academic study harder,” explained Bu.

The application was approved in 2004, and in 2015, the government permitted an increase of the run from 1,000 to 3,000 copies. Although it still ordered that buyer eligibility be restricted to selected experts and academics, Bu and Bai believed that the government approving an uncensored edition of the novel with detailed annotations was progress.

All these measure seem somewhat futile today. Chinese people today have easy access to the complete text of The Plum in the Golden Vase which can be downloaded from the Internet. Many readers have begun to rethink the novel, both its explicit passages and its other sections.

Some academics have publicly claimed that the descriptions of sex in the novel show an inherent resistance against sexual repression in the Ming, and indicates people’s hidden cry for sexual liberation, almost 300 years earlier than in Western countries.

Others spoke highly of the novel’s criticism of a corrupt society, especially the collusion between the businessmen and the bribe-hungry officials, with very similar reports appearing in today’s media.

At a sociology forum held in Jiangxi Province in June 2015, Chen Dongyou, then deputy provincial propaganda minister and also a historian, encouraged the audience to read The Plum in the Golden Vase to get a whole picture of the economy and social situation of the time. Given his official background, some critics even labeled his remarks a “re-blooming plum,” the “plum” referring to the novel.

At the forum, Chen emphasized that the novel’s main character, Ximen Qing, who seduces all sorts of women, multiplies his assets in seven years by business acumen and corruption and secures himself a place in officialdom, but finally dies of excessive sex, was of great realistic significance in today’s society.

His words were echoed by domestic and foreign critics alike, as Zhang Yihong told the New York Times, “You can find people like Ximen Qing easily today. Not just in China, but everywhere.”

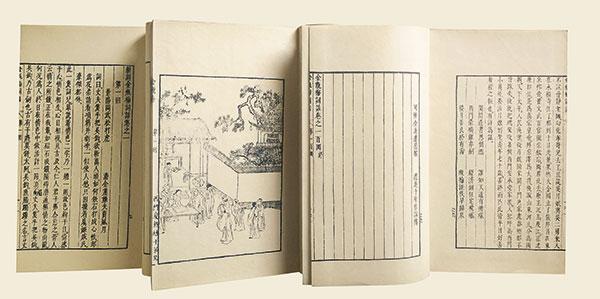

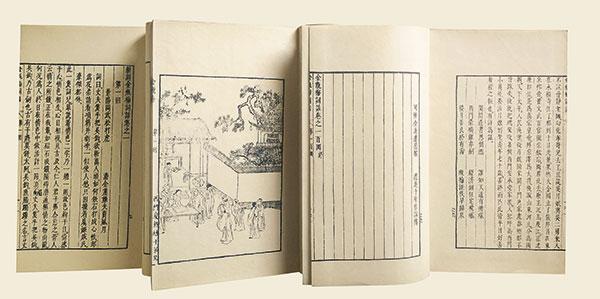

Old Version

Old Version