The Chinese public has paid close attention to the lost sailor’s fate, ever since the news of Guo’s disappearance broke. Many netizens showed concerns and sadness online, hoping the sailor could return safely.

Nevertheless, Guo Chuan’s adventures also aroused controversy. There are two distinct opinions on how to view Guo’s adventures as well as the meaning of sailing. Many netizens see Guo as a respectable hero, a nation’s pride, a great adventurer, but just as many question his deeds, and some even strongly criticize them.

Those who disapprove of Guo’s deeds see him as a “selfish” and “irresponsible” man who put his own interest higher than his fulfillment for family duties. Many cannot understand the meaning of adventures and believe what Guo did was nothing heroic, since it was only for himself and not for society.

“He was pushing himself to extremes. But did such challenges make any contribution to his family and his society? Or was he just doing it to satisfy his own interests, his sense of pleasure, the so-called sense of freedom, and putting all this above his duty to family?” a netizen with the handle “Baixuekui” commented on Sina Weibo.

“What’s the point of doing this [sailing]? It is understandable to sacrifice one’s life for the sake of your country like soldiers or astronauts. But risking one’s own life for adventures is totally pointless,” another Sina Weibo user, “Zhouyangfan,” commented.

“It is quite normal to have such arguments, which reflect the discrepancy of different values,” Zhang Yiwu, a famous social critic, cultural scholar and professor of Chinese in Peking University, wrote in his article, “Guo Chuan’s Fearlessness is Not Pointless.”

As Zhang indicated, traditional Chinese society attaches great importance to familial and social responsibility. Sacrificing for the public can be respected, but adventures based on individual ambitions won’t be accepted and understood easily.

Moreover, as Zhang pointed out, the urgent problem of material insufficiency has afflicted Chinese society for a century. The majority of Chinese were struggling to get rid of poverty, with no chance to try adventures, and found the idea of taking extra risks inconceivable.

“In recent years, more people are capable of pursuing their interests since their lifestyle is increasingly similar to that of Westerners. To pursue personal fulfillment and actively explore nature perhaps might not have a strong social influence, but still has its own value and meaning,” Zhang wrote.

Guo Chuan himself was constantly questioned over the meaning of sailing. “If I were French or British, I wouldn’t be asked such questions. People [in those countries] might be more interested in the details of how I overcame the challenge. Asking questions from ‘why you do it’ to ‘how you do it,’ the different angles of these two questions indicate an ideological discrepancy that might take dozens of years to make up,” wrote Guo.

In the eyes of professional skipper Gao Mingming, the significance of Guo Chuan and of sailing is seriously underestimated by society.

“Sailing, and pursuing dreams and meeting challenges, is not in conflict with family and responsibility. Each individual has his or her own right to live up to their best self, especially when they gain the support from their family. The deep-seated traditional familial and moral values, to some extent, restrain the imagination and creativity of Chinese people,” Gao added.

Apart from being a professional yacht racer, Gao also teaches and promotes sailing. “Sailing is one part of spiritual and cultural pursuits. I do hope every Chinese can have a chance to experience sailing and feel the beauty and infinity of ocean, which can change who we are and how we see life.”

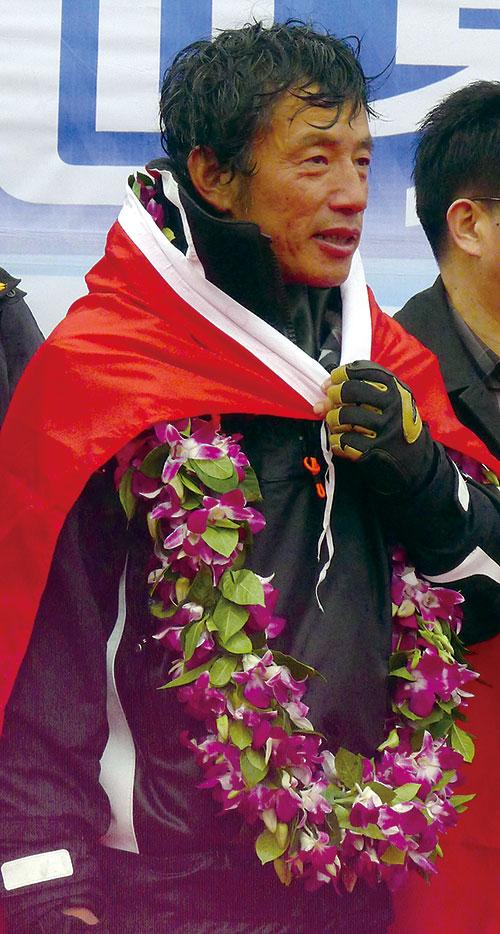

“I regard Guo Chuan as ‘the father of Chinese sailing’,” Gao stressed, “His solo non-stop global circumnavigation was the high point of Chinese sailing.” He compared Guo to Gol D. Roger, a fictional character in the famous Japanese manga One Piece, and the soul of the work as the pioneering “Pirate King.”

“Roger’s death does not stop the steps of those committed dreamers, but stimulates more and more followers to embark on the great voyage. Similarly, I see Guo Chuan as the real Roger in China. I firmly believe that more Chinese sailors, inspired by his spirit, will head out onto the ocean, and sail for the Grand Line,” Gao told NewsChina.

Old Version

Old Version