“We’re the gypsies of China,” a British friend of Hakka descent once told me. “They’re like the Jews of China,” I’d heard from someone else. There was something clearly a little different about the Hakka people of China’s southeast, but it was only when browsing the website of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites in China that I realized there was a whole lot more Hakka culture to explore. This is because the Hakka have traditionally built colossal, circular, fortified tulou roundhouses big enough to house several hundred people - an entire clan. I went to see some for myself, along with my sister, after persuading her it was the ideal use of her visit to China.

Heading for the Hakka homeland we flew to Xiamen, Fujian Province, and spent a few days exploring its markets and the piano-playing island of Gulangyu, acclimatizing to the southern humidity. From there it’s a hop by train across the bay to Xiamen Bei station and then a skip on a high speed train to the town of Nanjing where we negotiated with a driver to take us on a two-day tulou tour.

Within minutes of getting out into the countryside we saw our first roundhouses, a cluster of yellow-walled, tiled-roofed mansion-cum-castles. While we wanted to head straight over, the driver said they were nothing special and we should wait. He was right. Soon we were passing them every few minutes, ranging vastly in size and state of repair, but all the same deep yellow.

But it wasn’t just the tulou that looked like tulou. The architectural style has become a theme, creating a kitsch parade of novelty buildings deep into the countryside. Shopping outlets, restaurants and even a huge abandoned hotel mimicked the curved yellow walls and overhanging rooftops.

Guest Families

The term “Hakka” as pronounced in their own language, and as “Kejia” in Mandarin, means “guest families” and the area of southern Fujian where they have settled is not where the Hakka were originally from. There’s no authoritative history, but the general narrative is that the group is a subgroup of China’s majority Han ethnicity that originated along the Yellow River in central China, but first started migrating away in the third century after being attacked by other tribes.

Many migrations would follow until they reached the south of Fujian and Guangdong, and then from there, Hainan, Taiwan and the rest of the world. What makes them the “guest people” is that by keeping to themselves, they have retained their own languages and customs wherever they have lived. This in turn has led to resentment from people living alongside them.

However, we were now the guests. Arriving at our first cluster, Yunshuiyao, we fought through the carpark and tourism trappings for our first taste of the tulou twist on the Chinese architectural principle of “closed on the outside, open on the inside.”

Defensive Dwellings

Tulou (土楼) means “earthen building” and they are general made with a mixture of rammed earth and other materials including rubble, wood and bamboo. Rammed earth buildings are common across China, but Fujian’s are unique in their scale, intricacy and defensiveness. Some were built to house up to 800 people with concentric inner rings of buildings within the outer structure. They contain temples, schools, kitchens, dozens of wells and, most significantly, places to fire guns from and other fortifications.

This is because from the 12th century onwards, increasing banditry throughout the south caused the local Min people and Hakka alike to build defensive dwellings. It’s worth noting that the Hakka did not arrive building walls between themselves and their neighbors, but against later robbers.

As we entered through the huge doorway of Yunshuiyao’s Huaiyuanlou, we stepped into what is effectively a town in one building. Four stories of wooden walkways encircled temples and tea shops in the centre. It was very much still a home, with washing strung along poles and satellite dishes point skyward.

We began to understand how the buildings play into the non-hierarchical clan structures when we learnt that the buildings are sliced up like a cake between the families. Rather than a family within the clan having rooms side by side, every family has a stack of rooms with a ground floor kitchen and storerooms and then bedrooms and living quarters directly above.

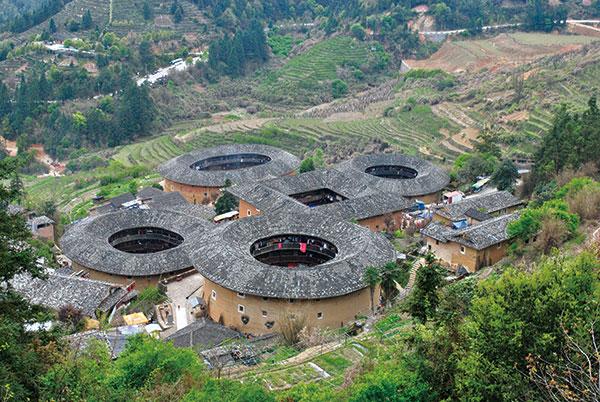

Yunshuiyao was pretty, but busy. Along a river straddled by bridges and dotted with banyans, there are dozens of round- and square houses to visit, including one with the faded slogan “Long Live Chairman Mao” on one side. It was the most heavily visited of all the places we visit, in part due to appearing in the 2005 film The Knot, and we soon moved on to Tainluokeng. This is perhaps the most iconic cluster as the village is made of a square tulou surrounded by three circular and one oval tulou, earning it the nickname “four dishes and one soup.” We arrived at a hilltop above with a viewing platform, then made our way down a winding path.

Just as salesy as Yanshuiyao, the crowds were thinning and we could have a good nose around, getting glimpses of kitchens and padlocked bedrooms. We met our driver who took us deeper into the countryside to Taxia village where we had booked a room in a tulou (very casually “yes, just drop by – there’ll be a room no doubt” the owner had told us on the phone). We had the place pretty much to ourselves and wandered around the creaking corridors while our hostess cooked a dinner of transparent-skinned dumplings.

We explored the village the next morning, long before any tourists arrive, stopping at intricate temples along the way to the Nanxi cluster. This was perhaps our favorite area. With beautifully preserved tulou all to ourselves plus the romance of traipsing through the ruins of vast structures, now filled with tropical vegetation and looking like an Indiana Jones set, we took our time, talking to the remaining elderly inhabitants about how the younger generations have left for the cities.

We stopped off at the surprisingly informative Fujian Tulou Museum (where we learnt that there are not only triangular tulou out there, but buildings overhanging rivers and even forming the shape of Chinese characters) and then headed for the Gaobei cluster, home of Chengqilou, the “King of the Tulou.”

Still occupied by the Jiang clan fifteen generations later, it’s got 370 rooms. But it’s the layers of concentric rings that make it so spectacular. Its four rings, shrinking from a four-story outer to a two-story inner ring followed by a single-story community library, end with the central ring surrounding the ancestral hall.

Their relative isolation also reflected inwards on the Hakka, making education and professions that do not require owning land, such as the military, very important to them, because they have generally settled in areas where the land belongs to other people.

The Gaobei set has one other significant treat for us: the pentagonal Wujiaolou (literally “five corner building”). We declined the many offers to ride horses and climbed the hill instead despite the torrential rain to see the roundhouses embedded in the countryside the Hakka made home.

Getting there To explore some of the most iconic and densely-packed concentrations of Hakka roundhouses, head to Fujian’s Yongding and Nanjing counties as a starting point (南靖 not Nanjing 南京, the large city in eastern Jiangsu Province). Nanjing can be reached in under 40 minutes by train from the nearest large city, Xiamen. Frequent high speed services leave from Xiamen Bei station, while just a couple of through trains a day go from central Xiamen Station via its airport, so simply change at Xiamen Bei. Public transportation around the settlements is unlikely to meet your needs so hire a car and driver, many of whom wait outside Nanjing station. Expect to pay 300 - 500 yuan per day, depending on your itinerary. Avoid public holidays when entire stretches of the countryside become gridlocked.

Practicalities

Bear in mind that the majority of tulou are still residences and should be treated with respect. Be aware that even after buying tickets to enter some of the tulou, residents may want to charge you extra to visit upper floors or see inside their homes. These areas are not necessarily covered by your tickets. Some tulou not named on tickets will want to charge you a “sanitation fee” to look around. Again, while this is not strictly allowed, locals rely heavily on tourism so if you don’t want to pay, it’s best to try another roundhouse.

Old Version

Old Version