High-energy physicists have one of the toughest jobs on earth; probing the mysteries of the universe. It takes a special kind of mind to tackle problems most people can’t even comprehend – and a whole lot of equipment and money. For years, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) developed by the Switzerland-based European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) has been the primary tool for particle physicists, after the earlier US Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) was suspended before completion in 1993 due to budget overrun. But China hopes to surpass the LHC with a Very Large Hadron Collider (VLHC), creating the world’s most powerful particle accelerator.

The VLHC is still being planned, but Chinese scientists say it will operate at up to seven times the energy level of the LHC, smashing particles and electrons together with massive force. They hope this will lead to the discovery of the currently hypothetical “Supersymmetric Particle,” allowing for a massive leap forward in our understanding of the universe.

The great puzzle of modern physics is that three of the four fundamental forces of the universe, electromagnetism and the weak and strong nuclear force, can be explained through our current “Standard Model (SM).” But the SM can’t be reconciled with general relativity, which explains the fourth fundamental force, gravity. The Supersymmetric Particle is expected to provide the missing link.

But while most physicists were keen to get their hands on the new accelerator, Chen-Ning Yang (known as Yang Zhenning in Mandarin), a Chinese-born US physicist who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1957 alongside his compatriot Tsung-Dao Lee, publicly argued against the project.

Yang said the VLHC will cost tens of billions of US dollars, but that its chances of finding the supposed Supersymmetric Particle are slim, since scientists have been questing for it for decades. But supporters of the project argued that science needs persistence and multiple experiments, and that the VLHC offers a huge chance for China to attract scientific talent and make breakthroughs in high-energy physics. As supporters like Wang Yifang, director of the Institute of High-Energy Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and famous Chinese-American mathematician and physicist Shing-Tung Yau, crossed swords with Yang in public over the issue, the arguments became fiercer and deeper.

Massive Collisions

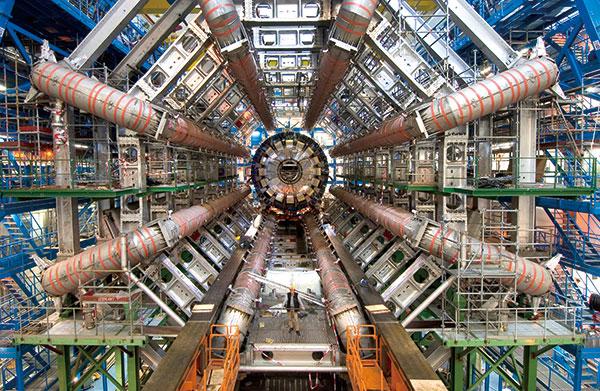

Particle accelerators like the LHC operate by using electromagnetic force to launch sub-atomic particles at extraordinarily high speeds, nearing the speed of light, in tight beams. Scientists crash them into each other to see if they will interact or produce new particles, and then compare their states before and after the interaction.

These experiments can imitate the origins of the universe itself, helping physicists study phenomena like the Big Bang, dark matter, the nature of gravity, and the universe’s many dimensions. By continually increasing the energy and number of collisions, scientists can discover more new particles, or more about the way particles interact.

China’s first particle accelerator was proposed in 1973 by Zhang Wenyu, then head of the newly established Institute of High-Energy Physics (IHEP). But due to the turbulent circumstances of the time, the project was canceled and a lower-energy accelerator was eventually built, the Beijing Electron Position Collider (BEPC), upgraded in 2008 to become the BEPC II.

The Swiss-based LHC is due to be powered off in 2035, and the BEPC II will end its service in the near future. That’s one reason why Wang Yifang, a well-known Chinese physicist who now heads the IHEP, proposed the VLHC in September 2012, arguing that the new equipment could allow even deeper research.

Wang’s proposal came just two months after the highly-publicized discovery of the Higgs Boson by the LHC team, a long-hypothesized particle that is an integral part of the SM. Under Wang’s design, a 50-100 kilometer long circular tunnel would be built 50-100 meters underground. A Circular Electron Position Collider (CEPC), of roughly the same power as the LHC, would be built first in 2021, followed by a hugely powerful Super Proton-Proton Collider (SPPC) in 2035 that would use the same tunnel.

Many scientists, Chinese and otherwise, back Wang’s plan. In 2013, the IHEP established a CEPC-SPPC team made up of 120 global physicists to study the feasibility of the program. A few months later, the Center for Future High Energy Physics was founded to work on the program, headed by physicist Nima Arkani-Hamed from Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study.

Shing-Tung Yau has been one of the project’s most enthusiastic backers, including publishing a book, From the Great Wall to the Great Collider (co-written with Steve Nadis), arguing for the program and explaining its scientific basis. Yau also helped fund several Chinese physics forums and sought government backing for the VLHC.

Yet the program is still only in its first stages. Around 300 scientists, representing 57 institutes in nine countries, have finished an initial design, and an area near Qinhuangdao, a port city in Hebei Province about 300 kilometers from Beijing, has been tentatively earmarked. Scientists believe that Qinhuangdao’s stable geology will better protect the project from earthquakes and other dangers, and the local government has offered a positive response to the idea.

Money Pit? But opponents of the project say it’s a huge waste of time and money. In his article, Yang vehemently criticized the idea that the VLHC could discover the Supersymmetric Particle. “Years of fruitless experiments have proved that the Supersymmetric Particle is just a scientific supposition. Many scientists, including me, believe that hoping the VLHC can discover this supposed particle is pushing supposition even further,” he wrote.

The VLHC would cost many billions of dollars to build, require massive effort from a devoted team of scientists, and consume resources that could go into smaller, perhaps more effective projects. Yang and others consider it to be a gamble that seems unlikely to pay off.

Proponents, however, pointed to the decades it took to discover the Higgs Boson, first proposed in 1964 by a team including the eponymous scientist Peter Higgs. The Higgs Boson was a fundamental part of the SM developed in the 1960s and 1970s, and the failure to discover it would have left a huge gap in the SM. But its discovery in July 2012 completed the picture of bosons, a particular type of fundamental particle, and opened the doors to further exploration to unify the SM with gravity and provide a “theory of everything.”

“The Higgs Boson is like the last piece to an old puzzle … We need to study if the piece is well matched or if there is still something we have missed. We have to find out the new clue of the next puzzle through the Higgs Boson,” Gao Yuanning, the high-energy physics director of Tsinghua University and a leader of the CEPC team, told NewsChina.

Some argue that the LHC is sufficient for this. But Chinese scientists say that the LHC produces “impurities” during the collisions and that a CEPC-equipped VLHC could create a much “cleaner” environment to study the new particles.

“A hadron collider is generally used to discover new particles and an electron positron collider focuses on studying the nature of a particle. We cannot give up subsequent research following a discovery,” explained Ji Xiangdong, a physics professor at Shanghai Jiaotong University who heads a Chinese project into dark matter project, an unidentified form of matter that makes up 27 percent of the universe, but remains a puzzle to physicists.

Han Tao, a physics professor of the University of Pittsburgh and VLHC project participant, shared his ideas. Han said that high-energy physics has entered a bottle-neck phase that needs to be bypassed with a new generation of energy collider. If China doesn’t seize the brief window, at a time when no similar project has been proposed in the US, and Europe is still busy with the LHC, it will miss the chance to become a global leader in high-energy physics.

Opponents, however, questioned just how useful these experiments are, especially given the time and money involved. The theoretical model used by most proponents of the VLHC, supersymmetry, remains unproven. They pointed out that the LHC has discovered nothing save for the Higgs Boson and thus the chances of finding a supersymmetric particle thus seem thin.

“None of the colliders, including the LHC, have discovered this supposed particle. Should we spend ten times as much money again to establish yet another collider to try and prove an already dead theory? What’s the logic to it? Is it really worth investing in pseudoscience?” Wong Meng-yuan, a Chinese-American Harvard physicist, wrote in an article responding to Yau’s enthusiasm for the VLHC for Taiwan-based paper China Times.

‘Long Keduo,’ a commentator writing under a pen name on www.guancha.cn, a popular news website, speculated that the VLHC would cost over US$50 billion, but that the possibility of it finding the particle was one in a hundred thousand. “The government should carefully consider whether the country really needs such an expensive toy,” he wrote.

Some foreign scientists have echoed these criticisms. In a letter to the Wall Street Journal, “Beware of these Chinese ‘Great Leaps’ in Science,” University of Washington physicist Jonathan Katz labeled particle physics a “mature, nay, dying branch of physics” and sarcastically described the new-generation of colliders as a “Great Scientific Leap Forward,” that would “starve scientific progress.”

Supporters, however, say that experimentation, even failed experimentation, is the core of science. “This is science – it’s the unknown and nobody can guarantee what we will discover. But if we do nothing, we’ll never know what we would have found,” said Ji Xiangdong.

Yau told the NewsChina reporter that the CEPC and SPPC would both supplement each other and work independently, saying that the CEPC can provide clues as to how to find new particles in the SPPC, while the SPPC will explore higher-energy collisions. Even if the SPPC isn’t built, he argued, the CPEC is a significant scientific tool by itself, not a “waste of money.”

“Once supersymmetry is verified, many high-energy physicists will view it as the greatest achievement of the science of the 21st century … We hope that China will be the first country to discover it. It will be of no less importance than China’s four ancient great inventions [the compass, paper, moveable type, and gunpowder],” said Yau.

Failed Dreams

The current argument is reminiscent of the fierce quarrels around the suspension of the US-based SSC in 1993. After the project was canceled, Nobel-winning physicist Steven Weinberg, who headed the SSC team, angrily argued that money was a huge obstacle to humanity’s exploration of high-energy physics.

In the 1980s, Weinberg’s team planned what would have been the world’s most powerful accelerator, with an initial budget of US$3 billion. But after the budget expanded to US$11 billion, it prompted strong political opposition. By the time the project was finally canceled, US$2 billion had been spent and only 20 percent of the work had been done. The LHC cost over US$6 billion to build, and requires US$1 billion a year in operating costs.

According to Chinese media, the CEPC would cost around 40 billion yuan (US$6.2bn) and the SPPC a massive 100 billion yuan (US$15.4bn). Although the program will invite foreign investment, China will cover most of the costs, amounting to about 30-70 billion yuan (US$4.6-10.8bn). Wang Yifang admitted that the program would be the most costly piece of research ever for China.

Gao Yuanning revealed that the government has approved 36 million yuan (US$5.5m) in funds for the preliminary research of the CEPC. However, this June, another 800 million yuan (US$123.1m) request for the program was rejected by only one vote.

It’s the sky-high costs that have really pushed opponents of the project, especially since initial estimates for large schemes almost always turn out to be too low. “China is still a developing country, with a per capita GDP lower than that of Brazil, Mexico, or Malaysia. Millions of migrants urgently need better lives, and there are other desperate needs, such as environmental protection, education, and healthcare,” warned Chen-Ning Yang. Some opponents went so far as to slam supporters like Yau for helping the US lure China into a “trap.”

Wang Yifang, however, argued that the VLHC’s budget is proportionally far less, compared to China’s GDP, than the BEPC 30 years ago. Supporters argued that the money will attract scientific talent to China and make it a global leader in physics, while critics pointed out that even the LHC hasn’t lured talent from the US to Europe.

There are also fears that the huge cost of the VLHC will mean less money and resources go to other, perhaps more fruitful branches of physics. But proponents of the VLHC argue that it can be part of China’s scientific renaissance, resulting in more interest and funding for everyone.

Right now, with the argument spreading to a public ignorant of science but highly conscious of where their taxes go, the future of the VLHC may be as much of a mystery as the secrets of the universe itself.

Old Version

Old Version