The legacy of Wang Zhizhi, the first Chinese athlete to play for the NBA, was marked by controversy when he prioritized his individual dreams over the wishes of his mother country

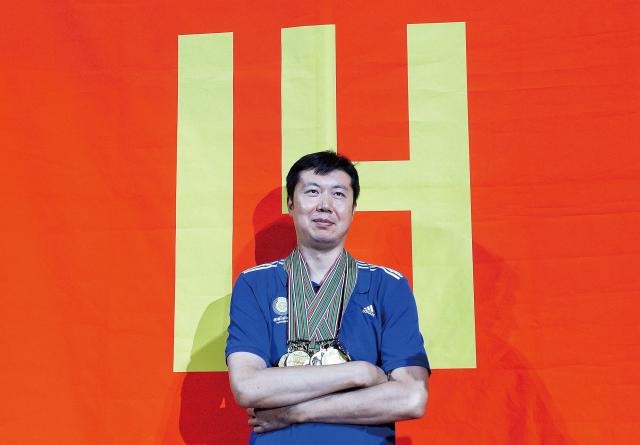

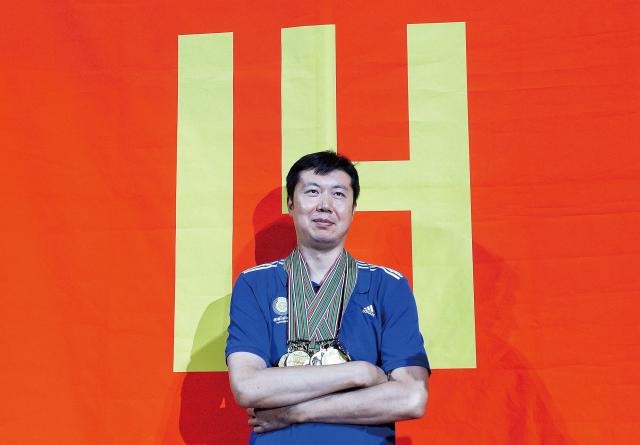

Chinese basketball star Wang Zhizhi poses during his retirement ceremony ahead of the first match of the FIBA Stankovic Continental Cup in Beijing, July 5, 2016 / Photo by Dong Jiexu

On July 5, 2016, during halftime of the FIBA Stankovic Continental Cup opening game, the Chinese Basketball Association (CBA) held a farewell ceremony for Chinese basketball legend Wang Zhizhi. This was a belated ceremony, held two years after the 39-year-old announced his retirement at the end of the 2013-14 season.

During the ceremony, Wang was honored with an award for outstanding contributions to Chinese basketball. Many of China’s best players, both past and present, attended the event to pay him tribute, including Wang’s former teammate Yao Ming and current national team captain, Yi Jianlian. The ceremony closed with 12 national team players successively stepping forward to hang 16 medals around Wang’s neck. Each medal bore a laudable achievement or moment from Wang’s 20-year career carved onto its face.

Wang’s career has been one of the most complicated in the history of Chinese basketball. His professional life both careened through smooth periods and lurched to sudden halts. Yao Ming once said: “The road taken by Wang Zhizhi was way more tortuous and difficult than anything most Chinese athletes have ever experienced.”

Apart from being a basketball player, Wang also served as a soldier. He joined the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) when he was 13 and later played on the PLA-sponsored team, the Bayi Rockets. He led the Rockets to seven national championships.

A basketball prodigy, he was the Chinese national team’s youngest player when he joined at 17, and later became the first Chinese athlete to play for a National Basketball Association (NBA) team when he donned a Dallas Mavericks jersey in 2001. He played for the Los Angeles Clippers and the Miami Heat in subsequent seasons.

As both a loyal soldier and an aspiring basketball star, he once famously struggled with a choice between following his individual desires or honoring the collective interests of his homeland. From early 2002 through April 2006, to pursue his NBA dreams, he opted to stay in the US and defied his PLA superiors’ orders to return to China. His insistence in chasing after his own goals made him a rebel to his fellow Chinese and came at its own price.

His quest and struggle paved the way for four more Chinese players to cross over to the NBA: Yao Ming, Yi Jianlian, Sun Yue and Mengke Bateer. One more is in the process of moving across the Pacific – Henan Province native Zhou Qi was selected by the Houston Rockets during the second round of this year���s NBA draft. “Wang Zhizhi might not have changed much, but he carved a hole into the wall that let his successors see the light,” concluded Su Qun, editor-in-chief of the newspaper Basketball Pioneers.

Wind Chaser

Our reporter spoke to Wang the week after his farewell ceremony. They met in the western suburbs of Beijing, at the PLA National Defense University stadium, where the Bayi Rockets train. In a dark blue polo shirt, looking neat and clean, Wang met our reporter with a polite smile.

Wang is currently the Rockets’ assistant coach. “These last two years, I have spent all my time in this stadium, teaching kids to play and staying in one spot,” he told NewsChina.

Born in Beijing in 1977, Wang grew up in a basketball family. At the age of 13, Wang’s parents, both former basketball players, sent him to join the PLA, where he received the best basketball coaching available in China at the time.

Wang signed his first professional contract with the CBA’s Bayi Rockets in 1994. He quickly grew taller than the rest of his teammates, sprouting up to a height of seven feet. His talent helped him outshine his peers, including Yao Ming. Fans dubbed him “The Wind Chaser.”

Wang soon proved himself to be a dominant force in the CBA. He led the Bayi Rockets to six consecutive CBA championship titles from 1995, the year when the CBA was first established, to his departure for the NBA in 2001.

In 1996, after Wang made an impressive Olympic debut in Atlanta, averaging over 11 points and five rebounds per game, the media predicted the 19-year-old would be “the leader of a new era” in Chinese basketball. “Asia is too small for Wang Zhizhi,” read an article in World Basketball Weekly.

On June 30, 1999, the Dallas Mavericks selected Wang Zhizhi in the second round of the NBA draft, making history by signing the NBA’s first Chinese player. But Wang’s journey to the US was far from smooth, because both the CBA and the Bayi Rockets refused to let go of their rising star. He ended up stalled in basketball limbo, between the CBA and the NBA, for nearly two years.

“The NBA seemed close at hand to me,” he once said about this long wait. “I felt like if I just stretched my hands out, I could reach it, but I also felt like my arms weren’t long enough.”

After a lengthy period of contract disputes and negotiations, Wang’s team and Chinese basketball officials finally let Wang go in April 2001. By the time he officially joined the Mavericks, there were only 10 games left in the regular 2000-01 season. Wang played during five games, averaging 4.8 points and 7.6 minutes per game.

As a part of the agreement signed between the Mavericks and Chinese officials, Wang had to go back to China in November of 2001 to play for his former team in the national playoffs. He helped the Bayi Rockets defeat Yao Ming’s Shanghai Sharks in the finals, making them the national champion for the sixth time in a row. Nevertheless, because of this he lost months of training time with the Mavericks, missing out on opportunities to study his teammates’ movements and practice the American style of play.

Struggle

Wang’s career took another stumble in his second year in the NBA. His contract with Dallas expired after the 2001-02 season. With no assurances that the Mavericks would invite him back the following season, the soldier decided to disobey the rules. He chose to spend his summer in the US to play in the NBA Summer League instead of returning to his homeland to train for the Asian Games with the national team, as previously agreed upon by the Mavericks and Chinese basketball officials. Wang moved to Los Angeles and fired his agent without informing the Mavericks or the CBA.

An article by Jodie Valade for The Dallas Morning News aggravated the situation further. Valade wrote: “Wang’s rebellion against the Chinese government may end in defection to the United States.” With the media stirring up trouble, his individual choice was blown up into a more serious problem with a political bent.

Two PLA officials eventually traveled to LA to bring him home. Wang told them that he was willing to play for China in the upcoming FIBA World Championships, but he would not return for the Asian Games. With his NBA future up in the air, the seven-foot center hoped to have one more chance to prove himself in the US.

His defiance ultimately got him banned from the Chinese national team in October 2002. In China, Wang’s rebellious absence was tantamount to treason. His public image in his home country was largely maligned by domestic media for four years.

Wang spent three more seasons in the NBA, one with the Los Angeles Clippers and two with the Miami Heat, but he never managed to become a regular rotation player. He ranged from an average of 4.6 to 10.9 minutes per game, depending on the season, and never saw a season average of more than six points per game.

The question of whether to stay in the US or return home hovered over Wang both on and off the court. One of his biggest concerns lay in his passport situation. Wang had a military passport, and the army declined to issue him a civilian one. He feared that if he returned to China and the army refused to release him once again, he would have no way of leaving the country on his own, ending his NBA career.

Over the next four years, Wang and CBA officials went back and forth on negotiations, but the two parties remained locked in a standstill.

“Wang Zhizhi’s mistake was that he put his individual interests far above the interests of society,” wrote then CBA Chairman Li Yuanwei in his autobiography. Li had met Wang several times in Los Angeles to negotiate his return. “It cost him four and half years to rectify his mistake,” Li continued. “But throughout this entire ordeal, the party that had the leadership role in solving this problem was the [government’s] sports management department. It failed to adopt a flexible, effective way to deal with the issue, which constantly magnified the problem and left it unresolved for a long time.”

Wang finally came back to China on April 9, 2006. Hundreds of reporters crowded Beijing Capital International Airport���s VIP areas and arrival gates in anticipation of his flight home, but the CBA had already arranged for him to exit through a covert passageway.

China’s online community had hurled insults at Wang while he was in the US, so the athlete was not sure what kind of welcome he might receive when he landed in his homeland. However, the first words he heard out of the passageway were “Welcome back, Big Zhi!” He immediately felt relieved. Not only was the greeting warm, but it came with the correct pronunciation of his name (the “Zhi” is pronounced “Jer”). In the US, nobody said his name right. Everyone called him “Wang Jee Jee.”

The only media outlet permitted to interview him off the plane was State broadcaster CCTV. In this on-camera interview, Wang openly apologized to the public for his stay in the US. “I was young and thoughtless when I decided to stay in America,” he said. “I’ve made some mistaken decisions. I apologize to the people of China.”

Three weeks later, Wang expressed his remorse again and begged all 1.3 billion Chinese people for forgiveness in a three-page open apology letter that was published in Chinese newspapers. “I’m sorry, I made a mistake,” he wrote. “Please forgive me and give me a chance to start over… I won’t let you down.”

Wang once again dominated the CBA. He earned the honor of 2007 MVP after helping the Bayi Rockets defeat the Guangdong Southern Tigers in the national playoff finals, leading the team to their seventh national championship. The Rockets have yet to reclaim this title in his absence.

His public image was completely resurrected after he helped China win gold medals in the 2006 and 2010 Asian Games, as well as in the FIBA Asia Championship in 2011.

In the 2010 Asian Games in Guangzhou, given that fellow Chinese legends Yao Ming and Yi Jianlian did not play, Wang served as the soul of the national team, singlehandedly hoisting China to the top of the podium. He scored 28 points to help China beat South Korea 77-71 in the finals. During the medal ceremony, the audience honored Wang with a standing ovation while all of his teammates hung their gold medals around the 33-year-old’s neck to show their respect and admiration.

Wang Zhizhi (right), playing for the Miami Heat, attempts to block the Houston Rockets’ Qyntel Woods, October 10, 2004 / Photo by IC

Back to Peace

Wang seldom talks about his past. He is especially reticent about his years in the US.

He has declined many publishers’ requests to write his biography. Li Yang, a sports journalist who knows him well, published a book about his tortuous career, but Wang said he hasn’t read it. Nor has he read any recent articles written about him.

He told NewsChina that the well-known novelist Hai Yan hoped to write a novel based on Wang’s experiences. “Hai Yan once said my story suited his [writing style] quite well; it’s full of twists and turns, it has ups and downs, and also involves conflicts between nationwide systems and individuals. It’s much more convoluted than other people’s stories.”

After he said this, he drew a straight line in the air and said: “Others’ stories are like this.” And then he drew a huge, wavy line, saying: “Mine is like this.”

Despite giving this interview, Wang said he has no desire to publicize his past. “I am not planning on telling my story,” he said. “I have my thoughts, but I won’t speak out. Nor will I post any of that publicly.”

Wang’s early 2000s dilemma, his struggle between the individual and society, is now regarded in China as a classic example of a moral quandary. It has been included as an examination question in ethics courses. The standard answers are usually given as “One should put national interests above all” and “A fault confessed is half redressed.”

Although he retired from professional athletics in 2014, Wang still leads a very disciplined life. “My current life is not much different from my previous one as a player,” he explained. “I start my morning exercise session at 6 AM, do three-hour training sessions both in the morning and the afternoon, eat at [school] dining halls, train for half the day on weekends. This routine repeats day after day.”

He likes watching cartoons. His son’s English name is Jerry, after the mouse in Tom and Jerry. He is also an obsessive collector of Transformers figurines. He plans to spend 500,000 yuan (US$75,000) on a gigantic one that is five meters tall, four meters wide and weighs two tons.

His greatest desire now is to spend the rest of his life exploring the entire country. “Our nation has more than 3,000 counties,” he said. “If I spend one day in each county, it will take me 10 years to achieve my goal. The distance between two counties in some provinces, like Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia, is so long that it might take ages to drive it!”

He developed an interest in reading books about history during his time in the NBA, especially those detailing the history of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). He had Chinese historian Ray Huang’s most famous book, 1587, a Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline, beside his bed, and talked animatedly about the historical novel Zhang Juzheng and British author Gavin Menzies’ 1421: The Year China Discovered the World.

He was very at ease – casually crossing his legs and holding one knee with both hands – when he talked through Ming Dynasty stories. Sometimes Wang looks to history to examine the vicissitudes of his career through a different lens. “If we use historical lessons to better understand the basketball court, we might find that all the waves and storms shall pass one day and peace will return.”

Old Version

Old Version