Chinese investors are keen to seize upon the potential of massively popular online stories. But is this a golden goose, or a blind alley?

A still from The Journey of Flower, an IP-based TV blockbuster released in 2015 / Photo by IC

For the last two years, Chinese investors in the entertainment industry have been playing their own version of Pokémon GO. The monsters they have been trying to catch are online novels, comic figures or video games with huge fanbases in the real world, collectively known as “super intellectual property (IP)” inside the industry.

Like Pokémon GO, catching this IP is just the beginning of the game. Just as Pokémon have to be trained through battles and gyms, so do the monsters of super IP through battle in the marketplace. Beijing Entbrains, a digital entertainment consultancy, estimated in a March report that the market of online novels and comics, the main source of IP, is currently worth US$7.6-15 billion, and that this IP could generate US$45-76 billion in business.

In 2015, 14 out of the 20 movies with the highest box office in China were based on existing IP, as were seven out of the nine most-viewed TV series made by Internet companies, according to Hou Xiaoqiang, former CEO of China’s largest online literature platform, Shanda Cloudary (later acquired by social media and gaming giant Tencent), at a Beijing seminar at the end of May. The most popular young stars now are those cast in TV series based on online novels published in 2015.

Last year was widely labeled as the “advent of an IP era” in the Chinese entertainment industry. However, as the market has already run out of super IP, the beginning of the new era faces as much anxiety and controversy as excitement over its prospects. The question of the hour: Can China create IP that lasts as long, and generates as much value, as Disney, Warcraft, or Pokémon?

Gold Finger

In 2006, Ghost Blows Out the Light, a novel about grave robbers published on qidian.com, an online Chinese literature platform, was sold for about US$60,000 to Huayi Brothers Media, a Beijing-based entertainment company. At an international IP conference in Beijing in April, Luo Li, one of the founders of qidian.com and the vice president of Tencent’s China Reading Limited, recalled that the novel was such a big success for them at that time that they spent much more than US$60,000 on the press release to celebrate the deal. He declared that he wouldn’t accept less than US$7.6 million for this novel if he had the chance to sell it again today. The film based on this story premiered last December, and made more than US$150 million at the box office within eight days. Only Hollywood blockbusters Furious 7, Transformers: Age of Extinction and Avengers: Age of Ultron achieved the same box office take in a shorter period of time in the Chinese mainland market.

Super IP can easily rake in this much dough. In a typical example in Entbrain’s modeling analysis, if 500,000 print copies of an online novel are distributed at US$4.50 each, the whole supply chain, including publication, TV and film productions, video games and other derivatives, will ultimately create nearly US$200 million in revenue.

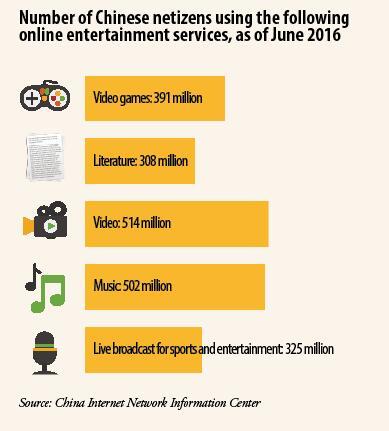

Online bestsellers began to attract major attention from the offline market in 2011, when several films and TV series based on those stories were hits. More such productions have been made in the following years, pushing up prices for good IP and making readership bigger than ever. The Entbrain survey valued the whole online literature market at US$1.5 billion in 2015. Although this was only equivalent to the annual revenue of two or three successful video games, the support of hundreds of millions of users cannot be played down, noted Luo Li. According to the white paper on China’s digital reading habits issued by the China Audio-Video and Digital Publishing Association in April, online reading platforms’ 296 million users in 2015 paid more than US$15 million for the top 10 publications. There are many more IP resources in online literature than in comics or games.

China’s three Internet giants, collectively known as BAT, in reference to Baidu in search engines, Alibaba in e-commerce and Tencent in social media, have encroached into the online literature market, and put nearly all major online literature platforms under their umbrellas. As Luo Li acknowledged, the most important tool they use to discover super IP is big data technology, which tells them who the most popular authors are and what kind of stories can attract the most fans.

A writer who goes by the pseudonym Maoni, one of the top authors on China Reading, has earned tens of millions of clicks with his stories. A cartoon based on one of his stories was released online in July 2015 and got hundreds of millions of views. The shooting of a film of the same story, starring Lu Han, a 26-year-old Beijing-born star, is underway.

According to a model produced by online consumption data provider iResearch in 2015, fans can contribute tens of millions of US dollars to box office takings and 4.3 million TV viewers to any show based on a Maoni story, which could in turn lead to US$323 million in box office earnings and 200 million potential viewers, far beyond the original fan base. Luo Li disclosed that China Reading has cherry-picked 15 super IP to develop films, TV series, video games, comics, stage performances, theme parks and other derivatives.

The IP-based film Time Raiders was released on August 5, 2016 on the Chinese mainland / Photo by IC

Weaving Gold

It is not easy to turn IP into gold. Firstly, the best IP have already been sold in the frenzy of the last few years, and potential new super IP are either uncertain or extremely expensive. China Reading’s 15 super IP are chosen from 10 million pieces on its platform, the largest of its kind in China, and the future of the 15 remains unclear. Other platforms do not have such huge reserves to choose from. They are all competing for popular authors’ next stories.

Lin, a 17-year-old in Beijing, told NewsChina that generally boys prefer games in which players have more control of characters, and this is why he does not like a recent game that is an expansion of a popular IP-based fantasy TV series. His preferences represent the other barrier for the success of exploiting the potential of IP – the popularity of an online story or game does not guarantee its success in other areas.

And fans’ interest never lasts forever. Even Disney struggled for years after its founder Walt Disney died in 1966, with the “Disney Renaissance” not coming until 1989, with the release of The Little Mermaid. IP buyers have to race against time to produce a hit before their copyright expires or fans’ excitement fades.

This is why some producers and directors complain that gambling on IP fans can lead productions down a blind alley. Director Zheng Xiaolong said at a TV gala in March that the original online stories only contributed a small part of the plot to his two successful TV series; the remaining aspects were created by his writers. At the same occasion, Hou Hongliang, a producer, said many people approached him with popular online novels after some of his IP-based TV shows were hits. However, he stressed that the professionalism of cast and crew is much more important than the original IP.

An IP-based love story was a success on TV screens in 2015. It was then turned into a movie, and although the latter also featured big name stars and had the advantage of increased attention thanks to the popularity of the TV series, was a flop. One important reason the movie bombed was that the producer, as the first IP holder of the novel, hastened to shoot the film before its copyright expired, resulting in what fans saw as a rushed movie.

Still from Ode to Joy, an IP-based TV blockbuster in 2016 / Photo by IC

Foreign Ideas

The wellsprings of IP in China can be hard to tap. That’s why well-established foreign IP have become targets of Chinese investors. The movie Warcraft, based on the long-running Warcraft video game series, particularly the hugely popular World of Warcraft, generated more than US$220 million at the box office in China by the end of July after its June release, nearly five times as much as its box office take in the US and more than half of its global total, according to data from Box Office Mojo, a site owned by the online movie database IMDb.

The movie is actually a China-funded project, underwritten by a partnership of three Chinese giants, Wanda, a developer which bought Warcraft producer Legendary Pictures in early 2016, Tencent and Huayi Brothers. Wang Jianlin, chairman of Wanda, told the media at a press conference announcing the Legendary deal about his ambition of fully exploiting the potential of Legendary’s IP-rich hoard by using IP not only for movie or game productions, but also for tourism and kids’ entertainment.

On June 21, Tencent declared that an agreement had been reached on a deal in which a Tencent-led consortium would buy controlling stakes in the US$10.2 billion Finnish game-maker Supercell, known for mobile games Clash of Clans and Boom Beach, from the Japanese information technology firm SoftBank.

Milking the cash cow of foreign IP might seem easy, but it’s been a little more difficult than investors expected. On August 2, Wanda announced it was shelving the Legendary acquisition in the consideration that it would take time for Legendary to restructure itself for the deal and prove its long-term profitability. Before that, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, where Wanda Cinemas is listed, and some media had questioned the business prospects of Legendary, which reported losses in 2014 and 2015.

Even if the recipe of foreign IP and young Chinese fans may work for a company, it is not the future upon which a big market like China can rely, let alone a feasible way to realize China’s ambition of promoting its cultural influence internationally. As a commentary in the China Cultural Daily argued, that cannot buy core competitiveness in an industry. Many people are calling for the encouragement of indigenous creativity. However, many writers are trying to join the bandwagon of successful IP. “They just repeat the story lines,” Wang Fang, editor of the online reading platform migu.cn, told our reporter. Analysts criticized this as a reflection of the overwhelming pursuit of instant success in today’s society.

The moral values of homemade IP are often controversial. Recent IP-based TV blockbuster Ode to Joy shows how young women with different family backgrounds climb through careers and marriages. At douban.com, a leading website for art and entertainment commentary, some posts criticized the show for showcasing not only the quality education, careers, and taste of its upper-class and middle-class characters, but also their lack of respect for others’ privacy and dignity, while portraying girls from less privileged backgrounds as stupid and vain. They said the story also tries to tell young people that the more you do for your love, the more you deserve to end up with a broken heart. Others do not like the idea of expecting an entertainment product to send the “right message” of social values, and believe it does its job well in reflecting one side of reality. Behind the division is the debate and anxiety also within the industry about what catering to the younger generation means.

These controversies show that the market values not only interesting stories, but also soul-searching ones. Whether that can translate into more box office hits is another story.

Old Version

Old Version