ost Western history texts state that World War II started when Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, leading to a declaration of war on September 3. But in recent years, this dominant Eurocentric interpretation of the WWII timeline has come increasingly under scrutiny.

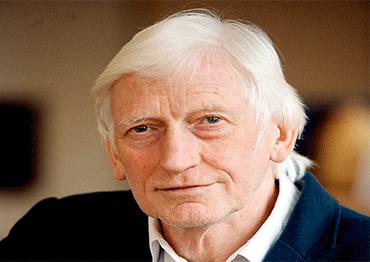

Professor Richard Overy of the University of Exeter in southwest England, a renowned British WWII historian, argues the war was ignited much earlier in 1931, when the Japanese army invaded Northeast China, which became the prelude to a global war. Overy first raised the argument in his book The Origins of the Second World War (1987), and elaborated on his conjecture in Blood and Ruins: The Last Imperial War, 1931-1945.

Published in the UK in 2021 and in the US in 2022, the book won several prestigious awards and was a New York Times bestseller. Overy argues that the breakout of WWII should not be understood solely as a European phenomenon, but as a global crisis triggered by “empire building” ambitions of Japan, Italy and Germany to challenge the old British and French empires. Japan’s invasion and occupation of Northeast China marked the first major step.

As Britain and France failed to hold back Japan’s expansionist ambitions, it not only emboldened Japan to embark on a full-scale invasion of China in 1937, but also encouraged Italy to invade Ethiopia in 1935 and Germany to annex Austrian and Czechoslovakian territories in 1938 and 1939, ultimately setting the stage for Germany’s invasion of Poland.

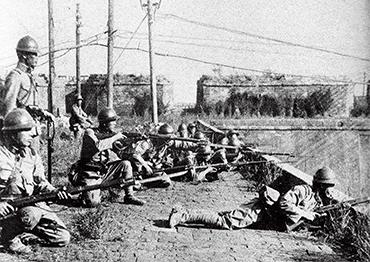

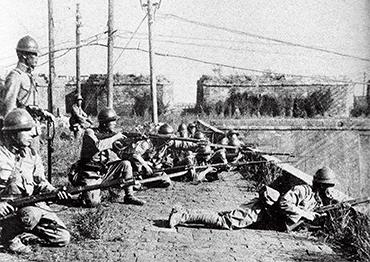

By tracing the starting point of WWII to Japan’s invasion of China in 1931, Overy has called to recognize China’s decisive role and huge suffering during WWII, which has largely been ignored in the West. The fierce resistance of China’s regular forces and guerrilla fighters forced Japan to fight a war on two fronts.

In December 2024, the Chinese-language edition of Blood and Ruins was published in China. The year 2025 marked the 80th anniversary of Victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. NewsChina interviewed the author for his insights into WWII. Overy stressed that human society should learn from the war to better protect civilians and avoid radical strategies in wars today.

NewsChina: In your book Blood and Ruins, you put forward a groundbreaking argument in WWII historiography that the war did not begin in 1939 with Germany’s invasion of Poland, but in 1931 with Japan’s aggression in Northeast China. Why did you put forward this thesis? Has your thesis been widely accepted in the West?

Richard Overy: So far, most people see WWII as a war against Hitler, about Germany, and the other wars that have taken place are less important. But it seemed to me that missed the whole point of the WWII, which is really a war of imperialism. You have to put it in the context of European global imperialism for the previous century. European states, and then Japan, began to expand territory in the 19th century and continued to do so after 1919.

I see the Second World War as the end point of 300 or 400 years of European global empire building. The crisis is a global crisis, not a crisis just about Germany. And I think that by looking at it in terms of imperialism is the only way you can make sense of what the Japanese, the Italians and the Germans are doing. They’re not just making war, they are seizing territory. They want to build a territorial empire to match the British and the French. And so that means fighting is just a way of getting the territory.

By the 1930s, territorial imperialism is out of date, that is what states did in the 19th century. But it doesn’t stop Japan or Italy or Germany. They believe that the only way to become a really “great power” is by acquiring a territorial empire.

That’s why I started in 1931, because Japan’s invasion of northeastern China is the first step in the effort of these three states to build an empire.

There’s been some disagreement, but I think on the whole people have been very persuaded by my thesis. I think that they’ve come to regard the traditional view of WWII as too Europe centered. And what they like, I think, is the fact you can now see WWII as a global event. It’s an event that takes place in East Asia, in South Asia and the Pacific, in Africa, in the Middle East and in Europe. The only place that is not touched is the US, but the US finally decides to engage in all these conflicts anyway.

NC: Japan did not decide to invade all of China at first. But was that an inevitable outcome, especially after the Japanese military gained power after 1936? If the League of Nations had put more pressure on Japan, could a full-scale war have been avoided?

RO: I think the problem is that Japanese leaders, military and civilian, are driven on by this idea that somehow Japan has got to challenge the West. It’s got to find a way of establishing itself as “the great power” in East Asia. And Britain and the US are about to stand in Japan’s way.

So I think it was always inevitable that they would drive on into China in order to prevent Western powers from blocking Japan. And by moving on to China and seizing more resources, what Japan can then do is turn around and fight with more prospect of success against the US and the British Empire. But without resources, Japan can’t do that. Japan in the 1930s would not have been able to challenge the US. Japan in 1940 had got all the mineral wealth of Northern China at its disposal. So this is really what drives the Japanese on.

It is possible that Japanese civilian ministers might have found a way to rein the army back. But I think the problem was that the army in Japan was very autonomous. So once it was in China, expanding, whenever it faced threat, it moved on until the final showdown with [the Kuomintang-led Nationalist government leader] Chiang Kai-shek in July 1937. But the Japanese are already thinking about how to dominate the whole of East Asia. It was therefore no accident that the war with the Chinese changed from a war of imperialism into a major conflict.

NC: How should we understand the connection between the global economic crisis in the 1930s and the war?

RO: I emphasize that in my book. I think the economic crisis is more important than what happens in 1919 [post-WWI]. I think in the modern world today, we can’t really conceive of really quite how dramatic that crisis was. The economic crisis convinces the Japanese, Italian and German leaders that in the end, if they want their populations to survive economically, if they want to build a decent living standard, if they want to become a major economy, they will have to have territorial empire, and they will have to control an economic block, just like the British empire, the French empire, or the US in the Americas.

And they link these two things together that in the economic crisis on that scale, you can overcome it by seizing resources and markets, by expanding territory, by getting access to secure food supplies. And that certainly helped to drive Japanese imperialism in 1930s.

NC: Many Western historians think the Nanjing Massacre (1937) was not as serious as other things that happened in Europe, or some people question the number of casualties. Why do people want to point out the differences between these tragedies?

RO: Unfortunately, that’s what historians do. But yes, there is a strong sense among Western historians that they’re already talking about the big crimes, German crimes against Jews, German crimes against Russians, there’s nothing quite like the Gestapo. Because they simply don’t know what’s going on in China. And Nanjing is just the tip of the iceberg of the number of the sheer millions of Chinese who died as a result of the war. I’m afraid it is difficult to estimate. The best estimate seems to be about 15 million, but there are wide variations on that. This is a huge number of people, and many of them are dying under atrocious conditions.

I think with Nanjing, the problem is the difficulty of getting precise statistics. It’s true of much of the bombing in Europe, for example, where the nature of the bombing meant it was quite difficult to get precise statistics about the number killed. So people would often make up a number. Historians have had to try to reconstruct what happened to provide a number that’s more realistic.

In the Japanese-Chinese war, I think that we’re never going to know the precise number. Records were not kept, people disappeared and we don’t know where they went. I think that we have to recognize that some historical pictures cannot be properly reconstructed, but there is no reason, absolutely no reason for thinking that the Nanjing Massacre did not happen.

NC: If we look back at the 14 years of war from 1931 to 1945, how do you describe or summarize the contribution of Chinese people among the allies in this war?

RO: There are a lot of argument about this. And I think Western historians have tended to be quite dismissive of the Chinese military effort.

The Chinese military effort was very difficult to mount. China had very limited industry, few advanced weapons. It was difficult to recruit and train the armies. But two things are important. The first is the Chinese are the first to challenge this new wave of imperialism. They were fighting against Japanese empire building from 1931 to 1939 before the war in Europe began. And I think that in itself is an important point, because nobody else was fighting effectively against the rise of this new imperialism in Europe, for example, until Britain and France decided to declare war on Germany. So from that point of view, China is in the forefront. China is the first state fighting against that imperialism.

The second thing is that the Chinese didn’t lose the war. They continued to fight from 1942 to 1945. The Japanese were not able to defeat them or to force a peace on them. They continued to resist. Whether they resisted well or badly, I think it doesn’t really matter. What matters is the Japanese could not conclude the war in China, which meant that they were facing all the time a war on two fronts: a war in China and a war in the Pacific. And for a country like Japan, which was relatively weak economically and industrially, to divide their forces and resources in that way meant almost certainly it would not win either, and they didn’t.

So Chinese resistance helps to maintain the Allied position in Asia. And I think that it’s time that Western historians come to acknowledge that fully. Imagine that Chiang Kai-shek gave up. The Japanese would have dominated the whole of China, and would have used all their imperial resources for the war against the Americans in the Pacific. It wouldn’t, I think, have been a different outcome, but it might have been a longer war.

Old Version

Old Version