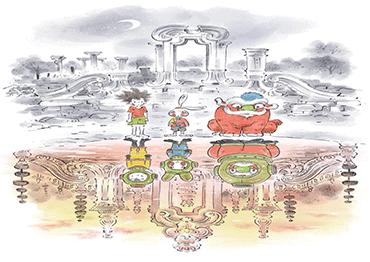

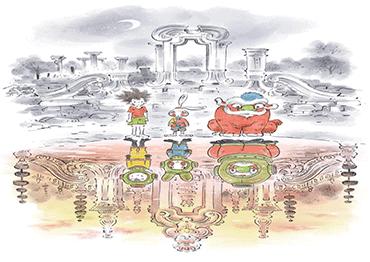

band comprised of Shanshan, a Danish girl and a group of Chinese gods of thunder perform a rock concert in Copenhagen, the city of fairy tales. They were brought together by a talking cat, who leads Shanshan into the Danish National Museum where she gets lost inside an ancient Chinese scroll. Shanshan helps the Chinese gods find their lost drum in Copenhagen, and the gods help Shanshan realize her music dreams, which also leads to a reconciliation with her father. This is the recently published Copenhagen Scroll by award-winning Chinese comic book artist Nie Jun.

Chinese children, like children anywhere else, are familiar with Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen’s classics such as The Little Mermaid, The Ugly Duckling and The Emperor’s New Clothes. With this new collaboration, visitors can also glimpse Chinese culture at the National Museum of Denmark.

Nie Jun was inspired to create Shanshan’s story by a Chinese scroll dating to 1596 in the Danish National Museum’s collection called The Thunder Department Goes on Out on Inspection, painted by royal artists at the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). The scroll depicts the gods who command thunder, lightning and rain, and bless people.

Born in 1975 in Xining, capital of Qinghai Province in China’s northwest, Nie moved to Qingdao, Shandong Province on the country’s east coast when he was a teenager, before studying at the prestigious Chinese Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Based on what he saw and heard in the old alleys and courtyards of Beijing, his award-winning graphic novel My Beijing: Four Stories of Everyday Wonder (2018), tells of disabled girl Yu’er who cannot walk and dreams of becoming a swimmer at the Special Olympics, and her grandpa. First published in Chinese, it was translated into French and from French to English. It has won several awards, including being listed among The New York Times Notable Children’s Books of 2018 and the Batchelder Honor Book in 2019. “With no fancy fight scenes or action shots, this is a slow and quiet delivery presented in a bright and warm palette of watercolors,” said book magazine Kirkus Reviews.

In an interview with China News Service (CNS), Nie said he feels that comic books can show the softer side of different countries. “I hope this comic book which tells a story about something taking place in the kingdom of fairy tales would make every ‘eccentric child,’ including me, very happy,” Nie said at the opening ceremony of an exhibition about the comic in January at the 798 International Art District in Beijing, curated by the Danish Cultural Center in collaboration with the National Museum of Denmark.

CNS: What was the inspiration behind the creation of Copenhagen Scroll?

Nie Jun: The National Museum of Denmark invited me to create this comic book. They wanted me to draw a comic book to attract visitors to the museum and learn about traditional Chinese culture. The inspiration came to me all of a sudden when I saw a Chinese scroll called The Thunder Department Goes on Out on Inspection in the museum. I was attracted by the spirits of the gods in the painting, or to put it in more modern words, the energy and rock’n’roll feeling they give off.

The main character, Shanshan, is a little Danish girl. By chance, she encounters the Chinese gods of thunder, and with their help, overcomes her own issues [of not feeling loved after her parents’ divorce]. In the end, Shanshan sings out loud at a party as she comes to terms with her life and begins to embrace the wider world.

When I was first creating this story, I felt there should be a weird kid with imperfections, which would make the story more interesting. But I gradually realized that kids nowadays always seem to hide their troubles deep down, and they don’t speak out. So I hope that my little readers can kind of give vent to their inner emotions through shouting and crying after they read the book.

CNS: What do you think is the power of comic books?

NJ: This is exactly what I asked the Director of the National Museum of Denmark [Rane Willerslev] right from the start: Why would a serious national museum approach a comic book artist for a collaboration? His answer was that children and young people find museums so boring they don’t want to come.

As fun as they seem, comic books are in fact quite powerful. There are things in them that many people might find speaks to them closely, very different from high culture, which people can find off-putting.

Just like a cute kid gently joining two adults’ hands together, a comic book can make the images of two countries, which otherwise look rather serious, more agreeable. And this is the power of comics. I very much agree with the saying that comic books know no borders. I’ve attended comic book festivals in Europe where many comics artists would draw each other’s caricature at the evening dinner, and that made everyone happy.

CNS: You have also visited Japan on academic exchanges. What are the similarities and differences between Chinese comic books and those of other countries?

NJ: China and Japan have different ecosystems for comic books. Japanese comics can be seen as products produced under a big commercial ecosystem, with a set of very established systems and ideas. And so is the European comics industry, which boasts its own ecosystem.

In terms of the content and expressive techniques, we influence each other. For example, many Japanese and European comic artists create works with Chinese themes or with oriental aesthetics. We are also learning some of their techniques. So there’s a kind of intermingling.

I think there is one thing in common among comic books from different countries, that is, all creators, no matter where they are from, are pursuing a better way of expressing how they see the world and themselves. Comic books need authors to present their own feelings in the pictures, including their own experiences of growth, which can be immediately reflected in the work’s lines, and the characters’ eye expressions, among other things.

CNS: The New York Times listed your work My Beijing: Four Stories of Everyday Wonder as one of its Notable Children’s Books. It also commented that “The stories move gracefully between reality and fantasy, a bit like Miyazaki movies, but sweeter.” How do you feel about this?

NJ: I really appreciate their remarks. I also feel they have found the empathy in this story. Although this work is about the life of an ordinary family in the hutongs of Beijing, they can easily discern something that resonates with their own wisdom, lifestyle and even emotions. Some of the small background props that I drew without much thought can be discovered by young readers of different countries, and they would tell me how they use them. I think this is the charm of images.

CNS: What are your expectations for Chinese comic books going global?

NJ: I very much hope that Chinese comic books can be read by readers in all parts of the world, but at first we ought to appeal to our local audience. I believe that as long as the work is particularly good and brilliant, it will be widely loved by overseas readers.

People often say that “good readers nurture good authors.” When great readers continuously give valuable feedback, authors can create good works. So we mustn’t rush to produce something that seeks quick gains, because they could easily ruin readers’ appetites, and slowly lower their tastes. As such, there would be less and less good works in the market.

In the future, we will create comic books on a broader international stage, and we don’t have to confine our target readers to a single country. So it is important for us to engage in broad exchanges. We need to find more common emotions, and use comics to eliminate stereotypes about each other so we can have more and deeper understandings of each other emotionally. As a comic book artist, I would feel it an honor to achieve something like this.

Old Version

Old Version