In addition to the momentum generated by the reality show Super-Vocal, a major policy shift by Shanghai’s municipal government gave a significant boost to the performance market. In May 2019, the city passed a regulation allowing any venue hosting at least 50 performances a year to be designated as a “new space for performance arts.”

One of the biggest beneficiaries of this policy is the Asia Building, a 21-story commercial tower located at People’s Square in the heart of Shanghai. Since 2019, the building has transformed from a typical office space into a key hub for China’s small theater scene.

Nicknamed “Vertical Broadway,” the Asia Building now houses 22 “star spaces,” each seating around 100 people. On any given night, musicals and plays run simultaneously in these venues, attracting over 2,000 audience members.

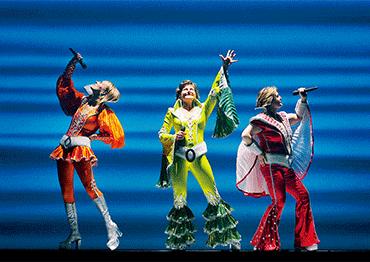

The most iconic production staged in the Asia Building is Mia Famiglia, a Chinese adaptation of a South Korean musical. Fans affectionately call it “Little Bar” due to its immersive staging – the entire set is a long bar where the audience sits, drinks and becomes part of the show. The result is a uniquely interactive experience that keeps fans coming back, some dozens of times.

Beyond repurposed commercial buildings, pop-up theaters have emerged in cafés, bookstores, teahouses, former factories and public squares. Since 2019, more than 100 new performance spaces have opened in Shanghai, collectively staging nearly 800 shows each month.

These venues have reshaped the domestic musical landscape. According to the 2024 Annual Report of China’s Musical Market, five of the top 10 highest-grossing Chinese musicals in the first 10 months of the year – Link Click, Doctor, #0528, Sonata of a Flame and Mia Famiglia – were all staged in Shanghai’s new performance spaces. All of the top 10 most frequently performed musicals were also produced and staged in these innovative venues.

Inspired by Shanghai’s success, other cities have begun adopting the “Shanghai model.” In cities like Guangzhou and Chengdu, busy pedestrian streets have become strongholds for small theaters. Guangzhou’s Beijing Road and Chengdu’s Chunxi Road are now home to fixed theater spaces where smaller productions are staged regularly.

“In grand theaters [in China], there’s no such thing as a Broadway-style musical that can run continuously for 20 years,” Yuan Qi told NewsChina. “Every production is scheduled for a limited run. Now imagine the cost of building a set for each show, dismantling it and transporting everything to the next location. If a show can’t be stationed in a permanent space, no matter how good it is, it’s just a ‘traveling show,’” he said.

Yuan’s company, Focustage, has been a major player in the small-theater scene, producing popular shows like Mia Famiglia, Mio Fratello, Supernova and Run for Your Wife in the Asia Building. As of now, Mia Famiglia has been performed over 1,200 times. Yuan believes that the city’s “new performance space” policy has resolved the longstanding issue of venue availability for small productions. In theory, he says, “as long as the building stands and audiences still want to see the show, it can run for decades.”

In 2019, when Super-Vocal first thrust musicals into the mainstream, Fei Yuanhong told NewsChina, “You can’t call China’s musical market a blue ocean. It’s not even an ocean. It’s just a lake.”

Today, China’s musical theater market is growing rapidly, but Fei has not changed his metaphor. “It’s still a lake,” he said. “But the lake is much bigger than it was in 2019. Compared to Broadway or the West End, or even Japan and South Korea, we’re still small. There’s a long way to go.”

Old Version

Old Version