Along with its commercial success, Chen’s work has also drawn criticism for its reliance on formulaic storytelling, lack of nuanced character development and emphasis on entertainment over artistic originality.

Many critics and viewers accuse him of being overly calculated in selecting subjects that tap into trending social issues to stoke public sentiment and boost ticket sales. Some see his approach as opportunistic and exploitative.

Detective Chinatown 1900, for example, has been criticized for promoting narrow-minded nationalism. Many argue its focus on racism and anti-Chinese sentiments in 1900s America leans too heavily into patriotic messaging.

“Chen is always so calculated. This time, he’s peddling patriotism and nationalism. I don’t want to be lectured during the Spring Festival holiday,” Shi Cuizhi posted on Douban, China’s leading media review platform. “This film encourages narrow-mindedness, provokes antagonism and agitates hatred,” another user Shengruxiahua commented.

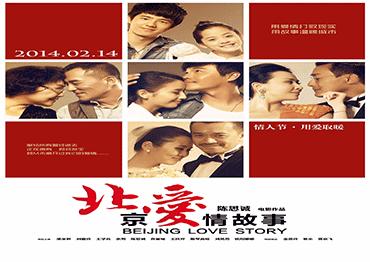

Similarly, Lost in the Stars, a mystery crime thriller written and produced by Chen, was criticized for exploiting gender-based tensions in China. The Hitch-cockian suspense film is based on a real-life case in which a Chinese man pushed his pregnant wife off a cliff in Thailand as part of a life insurance scam. The film was a huge commercial success, earning 3.5 billion yuan (US$483m). Yet many netizens criticized Chen for capitalizing on the growing mistrust toward relationships and marriage instead of delivering meaningful messages about feminism and female independence in a sincere way.

“I’m an audience member myself. I live in the same society. I experience, observe and care about the same issues they do,” Chen told NewsChina. “Being a director doesn’t make me different from most people. That’s why I understand what people truly want to watch and what kinds of stories they crave.”

He likens his filmmaking approach to “scrambled eggs with tomatoes,” a simple, universally loved Chinese dish. “A good film must appeal to both refined and popular tastes. Over the years, I’ve tried to create stories that people of different tastes can enjoy together,” he said.

The filmmaker has voiced deep concerns about the future of China’s film industry. He believes the market is in a “live or die” situation, as more people opt for short videos and streaming over cinemagoing.

“It’s not about whether the film industry is doing well or not, but whether it can survive. We’re facing problems that filmmakers throughout cinema’s century-long history had never faced before,” Chen said.

Movies are tied to cinemas as a primary distribution channel, which according to Chen is a particularly pressing issue in China as its industry is overly reliant on box-office revenue. “Cinemas can’t survive without profit. There is a critical threshold for China’s box office – if annual revenue falls below 48 billion (US$6.6b), 70 percent of cinemas nationwide would shut down. In 2024, we didn’t reach that critical figure. The country only took in 42.5 billion (US$5.9b) in annual box office revenue,” he said.

Given this reality, his top priority is staying active in the industry and bringing audiences back to cinemas. “At first, I felt hurt when people called me ‘product manager-like director,’ as I’ve always seen myself as a creator. But now, I accept it. Fine, I’m clever and calculated. The real competition isn’t from other films released in the same season, but other forms of entertainment – particularly short videos and short dramas,” he said.

Facing these challenges, Chen remains a pragmatist. “You have to rekindle audiences’ enthusiasm for film. Don’t stop, keep filming and do one’s best to bring audiences back to the big screen,” Chen said.

Old Version

Old Version