Unlike most writers who undergo a lengthy learning process in managing the media and public, Yu showed exceptional skill from the start.

“She is a natural-born genius not only in writing but also in thinking and talking,” Yang Xiaoyan, who helped Yu publish four collections, told NewsChina.

During interactions with media and the public, Yu often speaks in a witty, paradoxical and half-joking manner, both amusing and challenging her audience. She remains vigilant when media attempts to label her with “big words,” deconstructing them with humor, wit and ambiguity.

In her essay “To Live, Say No to Big Words,” compiled in her 2018 essay collection Rejoice for No Reason, Yu listed four labels that media, critics and netizens particularly like: suffering, tenacity, role model and purpose.

“By what standard do you judge my life as ‘suffering?’ Of course, disability may first come to mind. […] It’s undeniable that a disabled body causes lots of trouble and denies me of many possibilities. But one thing is equal: The soul in this body feels the world no less than anyone else’s. That’s crucial. True happiness comes from deep within the soul, not without,” Yu wrote.

When asked about what poetry means to her in our interview, Yu once again answered with her typical wit and sarcasm, “Do I really need to be rescued by poetry? I need to be rescued by a man.”

Yu manages to preserve the truest and sincerest part of herself in poetry. In 2019, she published the semi-autobiographical novel Lingering in the World and finished a 50,000-word novella this spring. “You can kill off your characters in fiction, but you can’t do that in poetry. Poetry is true and sincere. A poet should never lie in poetry,” Yu told NewsChina.

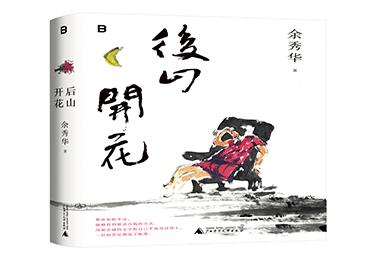

She delves further in her foreword for the collection Blossoms on the Back Mountain. “In my daily life, I am always a bit lax and idle. […] Poetry often pulls my wandering heart back to my body after a day of aimless drifting. It’s like a tunnel: when I enter, the entrance closes behind me, allowing me to carefully reflect on my gains and losses and find my place in the world.”

“I am so fortunate to have found the way that suits me best, using the truest words to place myself in the world, with all hardships becoming mere garnishes,” Yu writes.

Old Version

Old Version