Resurrecting loved ones has become a new business model for individual AI developers, but amid the hype, many people and even big tech companies are struggling to find paths to monetize the nascent sector

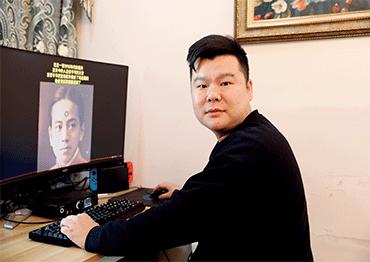

Screenshots from a conversation between a young man from Shanghai and an AI representation of his deceased grandmother

Days before Qingming Festival, also known as Tomb Sweeping Day, on April 4, Yuan Yan resurrected her grandmother without telling her family. Her beloved grandma died two years ago and her family chose to hide the news because she was busy preparing for a postgraduate entrance examination. Yuan has always felt regret that she could not say goodbye.

She found a tech company online and paid 1,200 yuan (US$165) for a service that claimed it could restore her grandma’s voice and expressions according to her specifications. She sent them photos and voice recordings. Now she can “talk” to her grandma when she has news to share, or just misses her. “I know she isn’t real, but it makes me feel better,” Yuan told Haibao News, a news portal based in Shandong Province.

Using AI technology to “revive” the dead has become big business in China, especially around Qingming Festival, when people traditionally pay their respects to deceased loved ones, either by going to a cemetery, or frequently, by burning fake paper money or even depictions of consumer goods for the deceased to use in the afterlife. A search for the key word “resurrection” on e-commerce platform Taobao yields a large number of ads for this service, with the charge ranging from tens to thousands of yuan, according to what people want. It is so popular that there are already training courses online teaching “resurrection” techniques.

This field is still rather niche, and big tech has neglected this corner of the market in favor of overarching ideas about how AI can provide grand solutions to humanity’s needs. Online, people offer AI services that fine-tune the existing text-to-image, text-to-video and text-to-speech generators and repackage them to generate products or services that can meet specific demands.

People look at an AI installation made from scraping online data in an exhibition titled Machine Hallucination, by artist Refik Anadol, Dusseldorf, Germany, May 2, 2023 (Photo by VCG)

AI See Dead People

Some products aim to fulfill emotional demands in a cyber world, such as chatbots or AI virtual boyfriends or girlfriends that were previously static, but are now in motion and interactive. Zhang Xiaorong, head of the research institute of manufacturing company Deep Innovation based in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, said the success of such businesses is because people more easily forgive mistakes, as the industry is so new, and they cater to actual demands from the public.

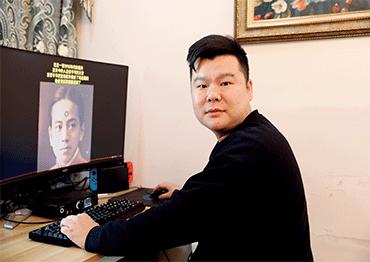

This is where digital resurrection comes in. Zhang Zewei provides these services. In March 2023, a friend asked Zhang, who was then employed in AI education and consulting, whether it was possible to create a digital version of his father who died in an accident. The friend’s family hoped the grandma could see her son still “alive” so they could continue to hide the tragic news from the fragile elderly lady. Zhang gathered videos, pictures and voice samples, and learned about the important experiences in his life and speaking habits. He trained the open-source model and eventually, the elderly woman conversed with “her son” in a real-time video. The avatar told her he just went to work in a faraway place and was too busy to return.

After that, more people contacted him. A mother who lost her only child hoped to see her daughter again. A wife hoped to talk to her deceased husband. Zhang realized that many people who were grieving were trying to heal in this way, and that it is a new opportunity that has commercial value.

Zhang told NewsChina that he was worried if big companies would notice the opportunity and squeeze them out, but he realized it is not very likely.

“We found that what the customers require are mainly customized products, which is not easy to standardize at scale.” He decided to go all in.

Zhang has two methods to achieve digital resurrection – training opensource models with videos, pictures, voice or other data to create digital people, or swapping the face of real people with the deceased to achieve more realistic interaction. He can usually deliver a product in five to seven days. The price of customization goes up to 10,000 yuan (US$1,382), depending on the requirements. If the user needs continuous training or the avatar needs upgrading, there will be ongoing fees. “The cost for us is mainly for personnel and computing power. The pricing is sustainable,” Zhang said.

Zhang has had inquiries from 2,000 people, and they have finished over 600. They have received orders for making virtual idols, though it is unclear whether these are imagined or real, which could plunge them into a murky world of copyright and image rights. Zhang is optimistic about the future. “Why can’t we keep data samples of our relatives or ourselves, so we can make our own digital self in the future, and they can accompany our children forever?” He hopes his team can develop a more standardized product to achieve this effect, and the birth of Sora, the latest AI model from the US-based OpenAI that can create videos from text instructions, makes him more confident.

But creating AI-cloned images and videos of the deceased, or the living, is controversial, and there are ethical and moral questions, in addition to issues over the safety and security of living people. Supporters believe that such technology can generate real value in companionship and making up for life’s losses and regrets. But many regard this trade as self-deception, questioning whether the “resurrection” is good for psychological healing. After all, loss is part of life.

More importantly, as Chen Yixin, director of China Insights Consultancy, pointed out, creating AI-generated videos of loved ones blurs the boundaries between the real and virtual world. There are complicated issues, such as whether family members have given informed consent to bring a loved one back to life, or who the “cloned” virtual people actually are. How should one view life and death when one can achieve digital immortality?

The increasing practice of creating AI-generated videos of dead celebrities has sparked much criticism and aroused legal concerns over the protection of the image and privacy rights of dead people. Recently, videos of several dead celebrities, such as singers Coco Lee and Qiao Renliang, were spread online. The AI “Qiao” said he was not really dead and had stepped back for a peaceful life. Qiao’s father told media that he feels uncomfortable about the video that was made without their consent, saying it is “bringing up past wounds.” Qiao committed suicide in 2016 at the age of 28, and Lee also took her own life in 2023, aged 48.

This business also involves security problems. As Chen said, in the process of resurrecting family members, private data is inevitably used. Then the problem is how to ensure data privacy and safety. What’s worse, the data might be used for fraud or vulgar purposes, as happened to US singer Taylor Swift earlier this year when AI was used to generate explicit images of her.

Chen said that companies need to strengthen their data security mechanisms and ensure data compliance. Industry standards and ethical guidelines are needed to guide healthy development of technologies. Individual users also need to raise their awareness of data security and be able to distinguish between the virtual world and reality to avoid being misguided, Chen noted.

AI Replace You

In the rush to get into this industry at the ground level, it is not only customers who must be wary of being duped.

Zhou Yi (pseudonym), a young woman working in an internet company, started to feel at risk of being replaced by AI when some of her colleagues started to do AI painting as a side hustle. When she found a livestream video by Li Yizhou, a vendor of AI training courses, she felt that mastering AI tools could help improve her career prospects. Under sales pressure tactics, Zhou ended up buying an introductory course for 199 yuan (US$28).

People like Zhou, who do not have grand ideas like big tech on how generative AI could change the world, just want to know what concrete benefits it could bring them. This includes improving their expertise or earning more income. That’s how AI pay-for-knowledge providers like Li, who attracted millions of viewers, are able to prey on consumers.

According to Feigua.cn, a data provider for short videos and livestream e-commerce, Li Yizhou’s online “Everyone’s AI Course” sold 250,000 copies in the previous year, with sales estimated to around 50 million yuan (US$6.9m), before his courses were all removed amid criticism about the quality from a lot of trainees.

Li is just one of the numerous individuals and companies in China who spot commercial opportunities, while tech companies engaged in developing large language models (LLMs) at high cost are still unclear where to make a profit.

After Sora was unveiled in February, AI-course vendor Li Yizhou became a hot topic on Chinese social media after a sarcastic meme, which shows him photoshopped side by side with Open AI’s CEO Samuel Altman with the title “Two AI Titans,” circulated widely online. This ridicule coincided with the contrast between the mushrooming of AI-related businesses by amateur players and the remaining gloomy market prospect for LLM developers, as well as the gap between technology development and application.

AI FOMO

Touting anxiety and opportunity is a typical gimmick to promote AI courses. As a popular saying in China goes, AI will not replace human beings, but people who can use AI will replace those who cannot. The advertisements for many courses of this kind boast that AI presents huge opportunities for anyone looking to change their destiny, sending the message that you either buy now or miss out.

One trainee on Li Yizhou’s course named Yidijimao on Zhihu, the Chinese version of Quora, signed up as he was attracted by Li’s background as a PhD from Tsinghua University (though in irrelevant industrial design and design innovation), and his supposed business acumen.

Individual AI tutors like Li often use their resume to attract potential students. They emphasize they are members of a research institute or worked for a top tech company.

Li’s course teaches about AI history, the core technology involved and application scenarios. Others target more practical needs, teaching people how to write prompts for tools like ChatGPT, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion, or professional skills like using AI to generate novels, illustrations, cartoons, animations, short videos or digital humans. Many pay-for-knowledge platforms that jumped on the trend, such as Netease and Zhihu, provide a more segmented curriculum that claims to improve people’s professional skills and efficiency.

The cost of these AI courses ranges from 1 yuan (US$0.13) for trial classes on platforms up to nearly 10,000 yuan (US$1,382).

However, the reality left many disappointed. According to interviews conducted by NewsChina, inexpensive courses often serve as mere introductory offers. Going any deeper means spending more. There are often hidden fees for accessing accounts for advanced products, AI tools and other services. Criticisms of such courses are common, with comments often citing “poor quality” and “superficial content.”

Yidijimao found Li Yizhou’s course disappointing too. He told NewsChina that the course over 40 lessons basically teaches “stuff you already know.” Li spent a lot of time trying to upsell an advanced course.

Zhou Yi was not happy with the course either, saying the content is rather shoddy and would only be of value to someone who had never read anything about AI. After Li’s courses were taken offline, Zhou said she will try to get her money back.

Jiang Han, a senior researcher with think tank Pangoal, agreed there are problems with AI training courses in general. “The quality is uneven. Some are too theoretical and lack real-life case studies. Besides, courses don’t keep pace with AI technology development. Some make false claims, misleading consumers that they could handle the technology easily,” Jiang told NewsChina.

Zhu Lin from Anhui Province uses AI technology to animate old photos (Photo by VCG)

A screenshot of Li Yizhou peddling his course on his livestream

AIming Too High?

But big AI investors regard these consumer-oriented applications of AI as low-hanging fruit. Zhang Jiang, CEO and founder of Longriver Investments told NewsChina that such businesses do not seem sustainable and their advantage might disappear immediately once LLM companies really move in to these areas.

In the meantime, LLM companies face challenges finding a profitable business model. These companies focused on mainstream commercialization of AI technology. It includes producing paid applications for consumers, such as photo editing and language tools, and providing enterprises with API interface services, embedded intelligent solutions, customized applications and cloud services based on large-scale models.

For now, AI apps are not profitable for most companies. Both their immaturity and high substitutability fail to retain users, let alone incentivize them to pay.

In such a new market that the public is still learning about, most companies either provide apps for free or halt development. Comparatively, more companies and investors are betting on training models that meet more vertical market demands.

But, despite the fierce competition among tech companies in developing LLMs, few are able to make money even after sinking huge sums into developing products. It is even harder to recover costs or make a profit.

Analysts said the immaturity of large models is the first hurdle for pushing commercialization. “Even though we believe AI technology has improved a lot, it’s still not good enough for largescale commercial use,” noted Zhang Xiaorong. He added that if AI makes mistakes, like adding extra limbs in an AI painting, users will tolerate it in a free entertainment app, but errors in sectors like autonomous driving, aviation and aerospace could have extremely severe consequences.

Many companies in entertainment, education, healthcare, finance, retail and manufacturing have declared they are willing to use AI. But in reality, even though AI can improve efficiency in the early stages of product development, a systematic solution that allows the use of AI in all stages has yet to come. Many links still require human labor.

“Despite the achievements Chinese companies have made in developing large models, technical challenges remain, such as model performance and stability,” Chen Yixin told NewsChina.

Large model developers’ lack of understanding about end users’ needs is also holding them back.

Zhang Xiaorong said that companies targeting consumers need to figure out how to improve user experience for individuals or enterprises.

“Products are accepted by the market only when you bring incremental value to users. Then they will generate economies of scale and turn technology into business value in a real sense,” Zhang said.

The development of large models is hindered by concerns over data privacy and security, leading to greater uncertainties about their commercial viability. The training and application of large models heavily rely on data, but with stricter laws and regulations over data protection, properly utilizing and protecting data is a problem the large model landscape has to face, Chen Yixin said.

Meanwhile, the sector’s intense competition has led to models and products becoming more homogenous. “Standing out among the numerous competitors with high-quality, unique and valuable services is a challenge,” Chen Yixin said.

Zhang believes these businesses might help promote the widespread use of large models, and the feedback of commercial applications also can stimulate technological improvement and innovation.

“Technological development does not always align with practical application scenarios. Large model companies, as technology developers, are sometimes too distant from actual market needs,” Chen said, believing that these businesses might prompt companies to explore more grounded potential scenarios.

Old Version

Old Version