Despite its popularity, Lijiang in Yunnan Province is criticized as being too commercial to maintain its ethnic authenticity amid arguments it is the only way to preserve its cultural legacy. Some suggest there is a middle way

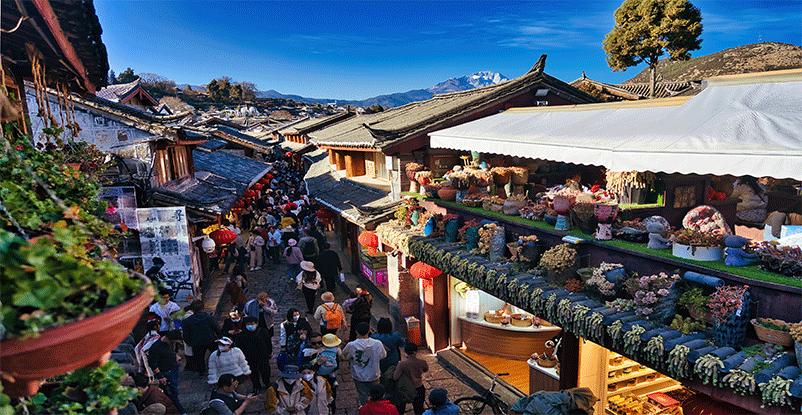

Tourists crowd the narrow streets of the UNESCO-listed Lijiang Old Town, Yunnan Province, January 26, 2023 (Photo by VCG)

Wearing silver hats adorned with tinkling bells and costumes made of floral prints sown in primary colors, tourists in the Old Town of Lijiang crowd the streets, bridges and rivers posing in “ethnic costumes.” The photo studio business to satisfy the social media age is booming in Lijiang, nestled at the foot of mountains in northwest Yunnan Province, previously an important stop for trade over the Himalayas. None of the excited posers seems to care they are wearing costumes worn by the Miao ethnic group, who live in the next-door province of Guizhou. The studios offer them as an attractive alternative to the more dour clothing worn by the local Naxi or Yi ethnic groups.

Outside one of the ubiquitous photo studios in the Old Town is a shop with pictographic Dongba characters, the pictographic writings of the Naxi language still in use today. Judging from the tiny column in Chinese at the left margin, the writings are a blessing to people for a prosperous future. But when asked what the exact meaning of the Dongba writing is, the two studio assistants who were about to shut up shop in the early evening on a November autumn day said that as Han people, they knew nothing about the Dongba language.

During the past few decades, the less than 7.3-square-kilometer heart of old Lijiang has struggled to maintain its ethnic identity. The former inhabitants, mostly from the Naxi, Yi and Lisu ethnic groups, have largely moved out under an overwhelming onslaught of commercialization. For more than two decades, many businesses catering to tourists in the old town have been owned and staffed by non-locals. The preservation of an authentic cultural legacy may be nothing more than a vain hope.

Local authorities have made efforts in the past few years to demonstrate they are paying more attention to cultural preservation. All the city’s road signs now carry both Chinese and Naxi script, and stores, restaurants, pubs and hostels in the old town have adopted bilingual signs in both Chinese and Naxi, where before, signs were only in Chinese. Yet still few understand the Naxi script.

Some experts on Naxi culture disapprove of such efforts. He Shangli, a retired educator-turned-official from Sanba Administrative Village in Shangri-La, 200 kilometers north of Lijiang, believes that depending on commercial tourism to spread the Dongba culture practiced by the Naxi is a reckless choice which does more harm than good in maintaining cultural authenticity. But others argue that without this commercialization, Dongba culture would be consigned to obscurity.

Lijiang Old Town is lit up at night, February 28, 2024 (Photo by VCG)

Dongba pictographs in the Naxi language on the wall of a shop translate as singing songs, Lijiang Old Town, June 10, 2018 (Photo by VCG)

Seeking Authenticity

On February 3, 1996, a magnitude 7 earthquake caused devastation in Lijiang. At least 333,000 buildings were damaged, including a large swath of the historic town center, leaving hundreds of thousands of residents homeless. Despite this, UNESCO still inscribed the Old Town of Lijiang on its world heritage list on December 4, 1997 following the post-quake restoration.

“The Old Town of Lijiang, which is perfectly adapted to the uneven topography of this key commercial and strategic site, has retained a historic townscape of high quality and authenticity,” said the UNESCO World Heritage Committee on its website.

From an insignificant town to an essential hub along the Ancient Tea Horse Road that traversed areas of the Tibetan Plateau from Sichuan to Yunnan several centuries ago, the town formed by lanes lined with wooden houses dotted with multicolored flowers, as well as the waterwheels, creeks and bridges that Lijiang is particularly known for, has been a popular tourist destination for years. The majority of the ancient buildings are renovated, occupied by hostels, bars, restaurants and gift shops, invested in by business startups. For many young people, settling in Lijiang and running a cafe or inn is a romantic dream.

However, over the past two decades, concerns and complaints targeting the commercialization of the Old Town have never ceased, not even when efforts were made to accentuate the town’s distinctive ethnic identity dominated by the Naxi group, including carving or painting legends about their origins on walls, or posting Dongba characters on planks, walls or columns. But these projects have not quenched the criticisms.

“Putting characters on road signs and doorplates alone cannot save a culture from the edge of extinction, not to mention the frequent mistakes in the writings,” He told NewsChina, adding “one cannot preserve an age-old cultural legacy without fertile soil nourished by dedication and beliefs.”

With origins in the nomadic groups known as the Qiang and Di, the Naxi are believed to have migrated from northwestern China in the upper reaches of the Yellow River and its tributary the Huangshui some 4,000 years ago. The area is in today’s Gansu and Qinghai provinces. But He’s research found they may come from what is today known as Ali Prefecture, Xizang Autonomous Region. The Naxi people developed a distinctive culture comprising polytheistic religion, rituals, divination, astrology and a writing system under both Han and Tibetan cultural influences, He said, based on his field research focusing on the Naxi migration. According to him, the culture is more complex than the characters on road signs, not to mention the commercialization that has more than once resulted in copycat waves of migration and identikit businesses that have devalued the Old Town in terms of cultural diversity.

From 2003 to 2017, with local government allowances and tax incentives issued to the residents in the town, many Naxi families moved out of their ancient homes to well-equipped apartments they bought in Lijiang new town, renting their houses to businesspeople, most of whom are non-natives, newspaper China Youth Daily reported in 2017.

A few years ago, veteran Naxiologist Zhang Xu, who is also the president of the Beijing Association of Dongba Culture and Arts (ADCA), knew a Naxi wood carving craftsman who made a living in the Old Town selling his handicrafts. In the beginning, the business was particularly lucrative when the unique indigenous artistic style attracted overseas tourists. But he decided to quit when an overwhelming number of stores started to sell the same products but at lower quality, causing prices to plunge.

The Naxi wood carver is not the only one to feel his craft was not protected. A Naxi calligrapher told Zhang that he spent so much time doing calligraphy for tourists that he had none left to explore his art. But the need to earn money left him no choice.

The problem of over-commercialization lowering incomes for Naxi cultural inheritors is not confined to Lijiang, but now has spread north to the rural Shangri-La area. The traditional ways of life remain in this area, He said, but urban Naxi do not care much now.

Xi Shenghua, in his 80s, lives in Shangri-La’s Rishuwan Village. His brother Xi Shanghong was a venerated Dongba, or priest in the Naxi language, but he said the glory days when his father was alive have gone. At that time, he lived in a well-to-do clan in the village, but when his father died, the family broke up. Now he lives on a meager pension which is not enough to refurbish his dilapidated house, he told NewsChina.

Much more needs to be done, other than allowing reckless commercialization of ancient towns and villages, Zhang said. Authentic Dongba culture is preserved nowhere but in villages and scriptures, among which Naxi explorations of the universe have been documented and passed down by rituals, divination and astrology. They cannot be understood without years of learning, Zhang said.

Forgotten Kingdom

In his book Forgotten Kingdom published in 1955, Russian writer Peter Goullart wrote a memoir full of deep personal recollections of his nine-year stay from 1939 to 1948 in Yunnan, in particular Lijiang. At that time, it was an important stop on the trade route from India to China during World War II, but still isolated by steep-sided valleys and mountains from the rest of the country. He wrote of the tranquil historic town, and the lifestyles, customs and beliefs of the Naxi, although he was also unsparing in his descriptions of the downsides of living in such a remote and poor area. But it has all gone now.

In contrast to the sequestered past, the Old Town today is engulfed by riotous bars where staff indulge in singing contests across the waterways, and stores festooned with bright lights to attract tourists. The commercialization has transformed much of the town, although some say it is an inevitable process if the Old Town is to survive.

Commerce has always been an integral part of culture, which can be exemplified by the historical role of the Ancient Tea Horse Road where the Old Town was a caravan halt, Zhang Yugen, a former deputy director of the Old Town’s protection bureau in Lijiang, said in 2021 in an interview with economic news site 21jingji.com.

Even today, the mountainous zigzagging horse trails remain a draw for hikers and tourists to enjoy horseback riding, Yang Xiao, a veteran Ancient Tea Horse Road guide, told NewsChina on April 2.

From 2012 to 2021, the added value of the tourist industry in Lijiang rose from 11.9 billion yuan (US$1.65b) to almost 29.4 billion yuan (US$4.07b), with an annual growth averaging 7.8 percent year-on-year, Chinese media outlet The Paper reported on August 8, 2022.

Different from He and Zhang Xu who expressed disapproval of Lijiang’s commercial transformation, Briton Duncan Poupard, a professor of translation of Chinese ethnic literature, especially Naxi literature, at the Department of Translation at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), told NewsChina that without tourism the Naxi’s Dongba culture would have sunk into obscurity.

“Commercialization is ultimately a good thing, because being more commercialized means more people can see it,” he said, adding that even though the presentation of the government’s promotion of Dongba writing is shallow and unauthentic, it has brought widespread recognition as more people are exposed to it and understand the pictographic characters a bit. “If you want to see real Dongba culture, you need to learn [about it] for many years. Most people don’t have that time,” Poupard said.

Poupard said he first encountered Dongba writings when he was backpacking in Lijiang in 2004. He found a dictionary of Dongba characters in a bookstore, and fascinated by the unique language, he decided to dedicate his academic research to understanding Dongba culture. His experience has left him a staunch supporter of Lijiang’s promotion model centered on tourism.

“More people in this world can see the characters and understand a little bit, the surface level, and that’s fine. Then maybe because of the commercialization for revitalization, some people could get the chance to go deeper. First they look on the surface, but then they would go deeper and deeper and learn more,” he told NewsChina.

However, Zhang Yugen, who also underscored the importance of commercialization in the Old Town, is aware that a well-designed tourism experience should not be separated from the influence of indigenous cultures.

To maintain ethnic cultures, three percent of the Old Town buildings have been preserved as museums and exhibition halls, where ethnic cultural inheritors display and sell their distinctive arts and crafts.

“But most of them are not good merchants and they can’t survive without governmental subsidies,” Zhang Yugen said.

Top: Naxi women in traditional costume dance with tourists in Lijiang Old Town, Yunnan Province, April 12, 2019 (Photo by VCG)

Bottom: A pageant is held in Lijiang Old Town, June 3, 2019 (Photo by VCG)

‘Nothing Concrete’

Despite the controversy of the commercialized Old Town in Lijiang, Sanba Administrative Village that governs the villages of Baidi, Dongba and Haba in rural Shangri-La is contemplating luring younger generations back by developing green agriculture and experiential tourism to create modern job opportunities. While quite a few young people still live in these villages, job opportunities are few and if they find a job in a bigger town or city, they leave and are unlikely to return.

“Unless young people join in, it will be hard to revitalize these rural areas,” Bao Jiang, a Naxi professor of sociocultural anthropology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences told NewsChina in March. According to him, agriculture alone cannot provide enough job opportunities for educated youth.

Like most rural areas in China, the exodus of youth from Sanba to neighboring cities including Lijiang and Shangri-La has continued to affect local development and cultural inheritance. Even though many of them might not earn very high salaries, perhaps only around 1,500-3,000 yuan (US$208- $416) a month, most are unwilling to return to villages after they experience a different way of life, retired administrator He Shangli said.

Village incomes are even lower, and people have more opportunities in urban areas, as well as access to schools and hospitals.

Yet the villages have bountiful resources that remain untapped.

Surrounded by snowcapped mountains including Mount Jiuxianfeng, Mount Haba and the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain range near Lijiang, the villages in valleys at the foot of the mountains enjoy yearlong mild weather, stunning scenery and a wide range of crops. The villages hope to capitalize on these natural assets to promote green tourism.

These aspirations were given a boost on November 26, 2023, when the railway between Lijiang and Shangri-La opened, reducing journey time to under two hours from a precipitous road journey of at least five hours. He Shangli said that after the railway opened, there has been an obvious increase in tourists to the area’s scenic spots.

Other plans include recreating the ancient houses of local ethnic groups, including Naxi, Tibetan, Yi and Hui in the area of the White Water Terraces (Baishuitai), a series of natural pools formed by calcium-rich water and sacred to the Naxi, some 100 kilometers southeast of Shangri-La, although this development is still in the planning stages.

He said they can establish museums that focus on ethnic groups, like the Naxi and their migration from the north. He emphasized that the plans must be different from Lijiang’s tourist industry. “We must win local approval and protect indigenous cultures properly before we put any plans into operation,” he said.

However, implementing these plans will take time.

“This is a plan designed before the pandemic, but there’s still nothing concrete. We need investment for infrastructure, transport, telecommunication, water and electricity, and we haven’t secured that yet,” Bao said.

Old Version

Old Version