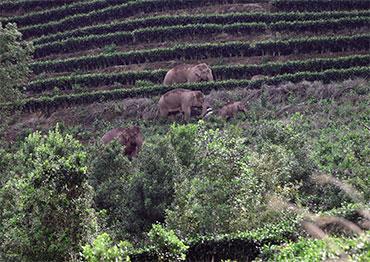

n mid-August 2021, a group of Asian elephants returned to their habitat in the south of Yunnan Province, after a 1,500-kilometer journey to the north of the province which started in March 2020. Now Yunnan is accelerating the designation of a national Asian elephant park, according to a report by the Yunnan Daily on August 11. The report came a day before World Elephant Day, which was created in 2012 by Canadian filmmaker Patricia Sims, director of the award-winning film about human-elephant relations, When the Elephants Were Young and the Elephant Reintroduction Foundation of Thailand, an initiative of Queen Sirikit of Thailand to improve awareness of elephant protection worldwide.

The elephants’ odyssey outside their habitat put the issue of elephant-human relations in the spotlight of conservation experts. A national park for Asian elephants was proposed at a meeting in July 2021 held by the National Forest and Grassland Administration and Yunnan Provincial government.

The purpose of the park is to protect the tropical rainforest, protect the Asian elephant species and its habitats and ease human-elephant conflict.

Citing Quan Ruichang, a researcher at Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Yunnan Daily says it will cover all three major Asian elephant habitats in Yunnan, including Xishuangbanna, where about 290 Asian elephants, or 80 percent of the Asian elephants in the province live, as well as the cities of Pu’er and Lincang.

With shrinking habitats, wild elephants are increasingly wandering out of the forest and entering human territories, resulting in escalated “human-elephant conflicts.” This challenge, which beleaguers countries with elephant habitats, is seen as an epitome of the global conflict between biodiversity protection and socio-economic development. What can be done? And what is China doing to address this elephant in the room? With these questions in mind, CNS talked to Chen Fei, director of the Asian Elephant Research Center, under China’s National Forestry and Grassland Administration and Ahimsa Campos- Arceiz, a researcher from Spain with the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden.

CNS: Last year, a herd of trekking wild elephants in Southwest China’s Yunnan Province caught global attention and brought attention to human-elephant conflict. Why does it happen, and what are its impacts?

Chen Fei: Conflict between humans and elephants is caused by the shrinking and fragmentation of elephant habitats. Human- elephant conflict is common in elephant habitat regions, and it can have devastating consequences. Over the past 100 years, the elephant population has declined due to habitat loss, ivory poaching and human-elephant conflict. The African elephant population has declined from three to five million to between 470,000 and 690,000, and the Asian elephant population has declined from 100,000 to between 40,000 and 50,000.

Humanity also faces serious threats and losses. In India and Sri Lanka, more than 100 people are killed or injured each year due to elephant incidents, and in Kenya, more than 200 people have died in the past seven years due to African elephant incidents. At the same time, local people also suffer significant losses of property. Some small farmers may even lose a year’s livelihood due to elephants who raid crops, while larger farms suffer enormous losses every year.

Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz: Human-elephant conflicts happen whenever we have people and elephants in the same landscape, especially if people cultivate crops. This is almost everywhere: Africa, Asia, and any kind of landscape, any kind of climate. So human-elephant conflict is a very pervasive situation. The main reason for the conflict is that we are ecologically quite similar, so then we compete for resources. The conflict has existed since ancient times, but as humans have appropriated more and more of nature’s resources for our own use, human interests have prevailed. The loss of natural habitat has brought elephants into more direct conflict with humans.

CNS: What have countries with wild elephants done to address this conflict? How does it work?

CF: With growing awareness of elephant protection, Asian elephants no longer fear humans, and they increasingly go out of their nature reserves to eat crops. Coupled with an increased population of Asian elephants, the conflict is becoming more prominent. In other countries, people mainly use biological, physical or chemical deterrents such as bees, chili peppers and tobacco to keep elephants away from farmland and human settlements, but very often drastic and confrontational measures make elephants even more aggressive. There are also countries which defend against elephants by growing crops that elephants don’t like. At the same time, managing problematic elephants for prevention and control is an important means: for example, each year, Malaysia will transfer elephants which have caused serious troubles to human life to other forested areas. Kenya’s wildlife conservation authorities shoot 50 to 120 problem elephants every year to protect local residents and cash crops. And countries like Nepal and Indonesia reduce human contact with elephants by methods such as building important migration corridors for elephants. People are yet to find better ways around the world to avoid human-elephant conflict.

AC: Human elephant interactions are very complex and very variable – they are context specific. We have different kinds of landscapes, different kinds of human cultures, also different kinds of elephant behaviors, and even different local histories of human-elephant interactions. So human-elephant conflict is not always the same everywhere, there are important differences from place to place, and even over time in the same place.

For example, in the Chinese case, what we have right now is very little natural habitat, so elephants live in a highly fragmented environment. Wherever elephants come out of the forest, they’re always very close to people’s houses and crops, with a lot of physical contact.

In Malaysia, as a comparison, we have far fewer people. Many Malaysian landscapes have been changed to plant extensive areas of oil palm and rubber. The main conflict there is economic – because of the damage to these cash crops – but there is not so much human-elephant contact, as few people are physically harmed by elephants.

We have places like Sri Lanka, where we have very high densities of both people and elephants. Although Sri Lankan people traditionally revere elephants and have very high tolerance for them, the conflict is now so intense that people’s tolerance is rapidly eroding. When this situation happens, people start to kill elephants in revenge for the human-elephant conflict.

So, when discussing the truth of the human-elephant conflict, the human factor, the Asian elephant factor, and environmental factors including local history need to be considered.

There are different combinations of situations, different places use different approaches, and even in the same place the approach has been changing over time. In many places, the more traditional way to deal with human-elephant conflict was to chase elephants away when they came to eat crops, and in many cases even just shooting them when the conflict was intense and persistent. Over time, there has been a change of values and the mitigation strategies have evolved. Shooting elephants is now illegal in all Asian elephant range countries and mitigation relies on physical barriers, like electric fences, problem elephant translocation to protected areas, economic compensation, warning systems, raising awareness to increase safety, and some other measures. The main difficulty is that [the conflict] cannot be solved. Whenever you have people and elephants you will have conflict. So then the objective is not to eliminate the conflict, but is to make it tolerable, to reduce it.

CNS: With joint efforts, the wandering elephant herd has safely returned to its habitat. What can we learn from this case?

CF: Through the successful management of the migrating elephant herd in Yunnan, we found that increased human tolerance of elephants, coupled with flexible intervention measures, such as food lures and pulse electric fences are effective ways to ease human-elephant conflict. But this undoubtedly requires massive input of human, material and financial resources, and is not a long-term solution. The most fundamental way to alleviate human-elephant conflict is to create a more friendly habitat for elephants. Apart from the area, forest quality and other necessary conditions, there are other things to consider, such as the huge amount of food elephants need, the scope of the area for their activity. Transformation and construction of their habitats and ecological corridors to link the habitats should be conducted on the basis of these factors. China is exploring further restoration of habitats through the construction of a national park for Asian elephants.

AC: Dealing with human-elephant conflict is a specific problem. In the process of the Yunnan elephant herd moving north and returning south, three beneficial experiences were gained.

I think what we learned is that, first, in China now people care about elephants. They are willing to allocate resources to protect elephants even if it’s a few individuals. Second is that the elephant population is very dynamic. Since the elephant population is increasing, they are also expanding geographically and going to new places. So, we can expect more and more elephants coming to places where people are not used to living with them. The third is that whenever elephants come to a new place, there will be problems. We need to anticipate these problems and work on reducing them before they become severe.

Yunnan has made strides in accident compensation, early warning and multi-department cooperation. These experiences will help to deal with the problem of human-elephant conflict in the future.

CNS: Compared with its international peers, what innovations will China’s Asian elephant park have? Will it provide a solution to human-elephant conflicts?

CF: Compared with existing national parks elsewhere in the world, China’s national park will have its own distinctive features. First, more emphasis is placed on conservation. China has positioned its national parks as the most important type of nature reserves, with the most strict, scientific and standardized conservation management, as well as more focus on protecting the integrity of the ecosystem.

Second, there’s more emphasis on system construction. China is capable of constructing an integrated natural reserve system centered around national parks and building an effective and long-term mechanism for habitat protection.

Furthermore, there is emphasis on the combination of ecological protection and community development. When the US, Canada, Australia and other countries set up their national parks, there were huge areas of wilderness and uninhabited land. With a small [human] population within those national parks, the conflict between wild animals and human communities was not a big issue. But China has a large population, with villagers within national parks. There are also temporary tents for herders in their winter and summer pastures within parks. Therefore, China has focused more on community and livelihoods in its efforts to construct and conserve national parks. With scientific planning, reasonable zoning, differentiated policies and management, local communities are partnering in the construction and operation of national parks to pursue the win-win situation of a “beautiful ecology and prosperous community.”

In addition, the Asian elephant national park, which is currently under planning and construction, has come up with innovative practices, such as preserving part of the agricultural land where Asian elephants are concentrated, establishing a crop compensation mechanism to supplement a source of food supply for Asian elephants, as well as attracting elephant herds to return to and live in the forest, so as to ease human-elephant conflict and ensure harmonious coexistence of humans and elephants.

Right now, elephants are entering human territories in an unprecedented scale, which presents challenges to traditional means of reducing human-elephant conflict. Solving the human- elephant conflict is not only about the harmonious coexistence of humans and animals, but also a test of the wisdom and courage of humanity. The good news is solutions are becoming increasingly flexible, multi-dimensional and sustainable. Only this way is suitable for both human development and wildlife development. I believe the Asian elephant national park, which is constructed with an idea of comprehensive protection, will bring fundamental changes to the alleviation of the human-elephant conflict in the region.

AC: There are two main objectives. The first is to protect tropical rain forests in China, and the second is to protect Asian elephants. Protected areas, especially large national parks like the one currently being planned, are the most effective tool for biodiversity conservation in the long-term. In the case of Asian elephants, it is important to note that national parks are not enough for conservation, because elephants like habitats outside protected areas and will continue approaching human settlements and crops. But, despite this, the national park is a great contribution to Asian elephant conservation in China. I think the main difference [from traditional natural reserves] is the scale in the integration of humans in the systems. It involves a much more holistic, more complex, but more integrated management. North America, where the national park [movement] started around 150 years ago, has very low human density and places with very little human presence and relatively pristine landscapes. I think national parks like this one in Xishuangbanna is going to have a strong element of restoration, not only protecting what is there, but kind of bringing back something.

The establishment of an Asian elephant national park in China will create a new model and accumulate more experience to better solve the human-elephant conflict and even the relationship between man and nature.

Old Version

Old Version