Old Version

Old Version

A ceiling fresco in the Louvre Museum, Paris

A famous painting by Gu Kaizhi (around 345-406). The painting is based on a classic poem by Cao Zhi, a prince who lived during the Three Kingdoms period (220-280). The poem tells a romance story between Cao and the nymph of the Luo River. [Photo from HKPM official website]

A portrait of Qing Dynasty Emperor Yongzheng (1722- 1735) likely painted during the reign of Emperor Qianlong around 1750, Palace Museum collection. Like other Qing portraits, the likeness, temperament and exalted status of the Yongzheng is captured in a dignified and extravagant style. [Photo by VCG]

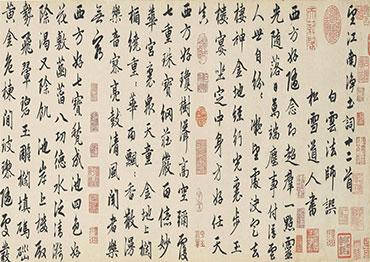

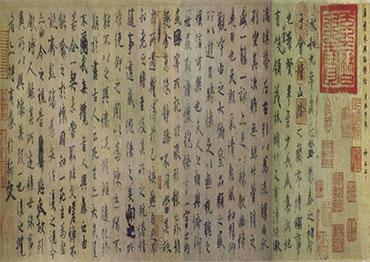

A calligraphy work by Zhao Mengfu (1254–1332) of the Yuan Dynasty, Chinese University of Hong Kong Art Museum collection. Among the greatest calligraphers in Chinese history, Zhao rejected the gentle brushwork of his era in favor of the cruder style of the Jin (266-420) and Tang (618-907) dynasties. [Photo from HKPM official website]

A ceramic work from the Ding Kilns of Hebei Province in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Headrests like this were popular during the Song Dynasty. Qing Dynasty Emperor Qianlong (who reigned from 1735-1796) loved this headrest so much that he composed many poems about it. [Photo by IC]

A work by Tang Dynasty calligrapher Yu Shinan (558-638), Palace Museum collection. This is Yu’s copy of a famed calligraphy piece by the great calligrapher Wang Xizhi (303-361) of the Eastern Jin Dynasty. [Photo from HKPM official website]

A silk painting by an unknown imperial painter in the Qianlong Period (1736-1795) of the Qing Dynasty, Palace Museum collection. It depicts the annual tribute missions of foreign delegations to the Qing court in the Forbidden City to mark the Lunar New Year. [Photo by VCG]

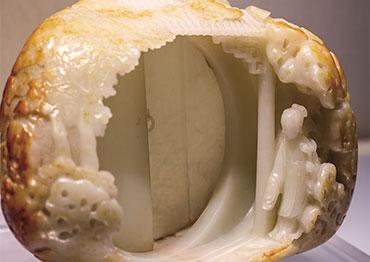

Jade (nephrite) sculpture from the Qianlong Period (1736- 1795) of the Qing Dynasty, Palace Museum collection. A poem by Emperor Qianlong (who reigned from 1735- 1796) is inscribed on its base. Qianlong lived to be 87, longer than any Qing ruler, and wrote more than 42,000 poems in his lifetime. [Photo by VCG]

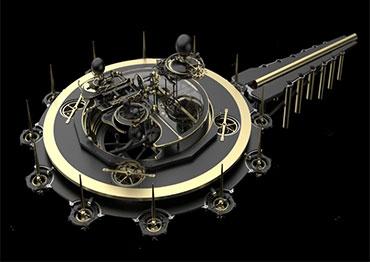

A kinetic sculpture by Hong Kong contemporary artist Joseph Chan. Inspired by a mechanical clock used in the Qing Dynasty court, Chan attempts to blend modern clock-making technology with traditional mechanical clock designs to juxtapose two times – past and present – in one artwork. [Photo from online source]

An aerial view of the Hong Kong Palace Museum, May 29, 2022