Food can be unintentionally divisive. Every nationality has dishes that makes the heart sing, and lines in the culinary sand that they dare not cross. Chinese cuisine is wonderful and worthy of extensive culinary exploration for any true foodie. In fact, for an adventurous eater like myself, China is a thrilling paradise of variety. However, even if newbies to China love most of what they nosh on here, there are still some peculiarities that require time to get used to. Whether it’s the stinky funk of a century egg, or the challenge of eating around those small slender bones on a slice of Hainan chicken.

For those with special dietary requirements, the challenge is even greater. There are proportionately less strict vegans and vegetarians here than in Western countries, but I’ve found that it’s still not uncommon to find people with special diets. Among foreigners here in large cities, vegetarians are a dime a dozen. For such individuals with special diets like gluten-free, being vegans or vegetarian, eating out can be tricky. Most national cuisines in China emphasize the need for balance within dishes. Chefs commonly like to mix in bits of meat, or oil that has just cooked meat in their vegetable dishes to add flavor. Adding things like flour or glutamate to dishes that would otherwise not have them is also common. I’ve been out to eat with many friends who find ordering to be quite a challenge.

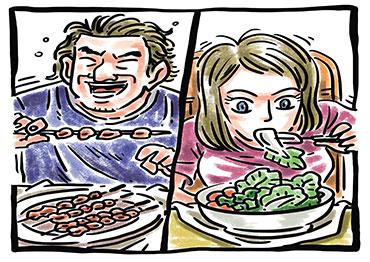

Ewan, a 38-year-old Irish foreign trade worker whom I met at a quiz night two years ago, was diagnosed with ceoliac disease as a teen – an intolerance to gluten. Though he loves all things bread, he won’t hesitate to joke with you about how bread doesn’t love him back. He’s a 10-year China veteran and has learned ways to live with his condition despite the prevalence of hidden gluten in Chinese dishes. One tactic Ewan uses to avoid catastrophe is to stick to protein. Whenever we dine together, he always wants to go for shaokao, or Chinese BBQ. He says it’s so he can see his order being grilled and speak up if he sees any problematic additions.

Shaokao isn’t always the answer though. Alissa is a friend from a WeChat group for foodies. She’s from Italy and is just 25. She’s studying Chinese language at a university in Shandong Province. Alissa’s been vegan since high school due to her passion for animal welfare. She cooks in her dormitory kitchen more often than she eats out. “During my first month in China, I ate tons of chips, but life’s gotten better since developing my Chinese. Learning to not get upset if I happen to find chicken in something I thought would be meat free has also helped.” One of the first words she mastered in China was the phrase “sude.” It effectively means vegetarian but literally translates to “plain” or “bland.” Once she told me that every time she uses this word, she secretly hopes that she’s not actually given bland food. Alissa has also told me countless stories of connecting with locals. She loves sharing the rationale behind her dietary choices. She widens their view of what other nationalities eat as much as they widen her own view of the world.

My coworker at the high school I work at, Johnson, is a Dutch citizen of Hong Kong descent. He’s our physics teacher. As a Buddhist-vegetarian, he faces more challenges than Alissa does. As he explains it, Buddhist-vegetarians come in many varieties. Some, hailing from northern Asia, avoid specific potent ingredients like garlic, but dine freely on chicken and eggs, confusingly enough. Others like him follow a normal vegetarian diet, but have the added challenge of avoiding certain ingredients and strong herbs, like leek. He makes up for the lack of flavorful herbs through his consumption of dairy products. I’ve noticed that his favorite lunch or snack at work is a buttered bagel. In Taiwan and Hong Kong, Buddhist-vegetarianism is well-understood. Simply telling an establishment that you are Buddhist is generally enough to ensure a hassle-free eating experience. However, in the Chinese mainland, Buddhist-vegetarianism is only accommodated properly at religious restaurants near temples. My friend advises that anyone with similar dietary restrictions avoid eating out during busy times. It’s easy for a waiter to misunderstand you, or for a chef to forget to skip the garlic when they’re rushing.

Having a special diet doesn’t have to mean lackluster restaurant experiences for those living in China. Developing adequate language skills, with the ability to clearly explain your diet to others seems to be crucial. Keeping an open mind and a lighthearted attitude for a people still learning to cope with being on the international stage also helps immensely.

Old Version

Old Version