Pritzker prize-winning architect Wang Shu is working to save China’s traditional architecture for future generations, one village at a time

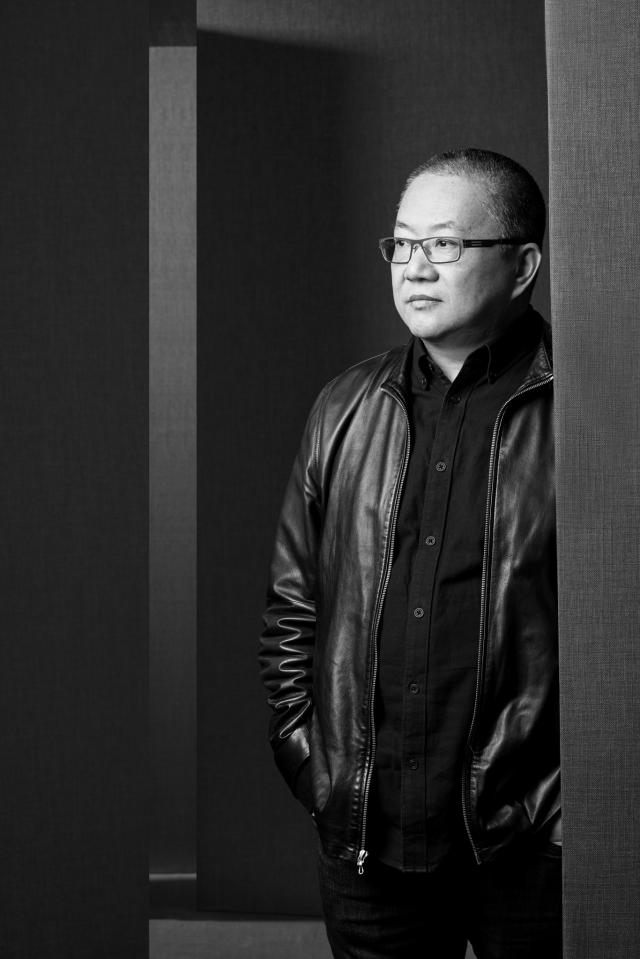

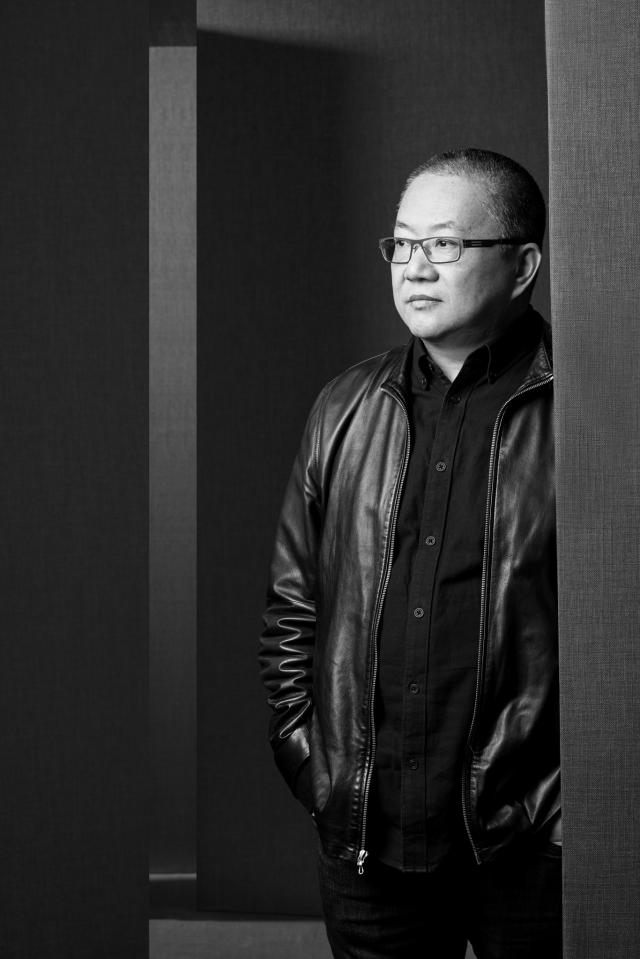

Wang Shu calls himself an “amateur.” He even named his firm Amateur Architecture Studio. But his work says the opposite: The 57-year-old architect is China’s leading advocate for traditional building techniques as a way to preserve Chinese culture and history.

China’s rapid urbanization has spawned cityscapes full of what Wang calls “professional, soulless architecture” – swaths of homogenous modern buildings that forsake China’s architectural traditions. And Wang is out to challenge them.

“While modernization is irreversible, I don’t think it’s as powerful as it seems,” Wang told NewsChina. “There are some potential risks in [China’s] current environment and ecosystem. The reason I’ve spent years focusing on rural construction is that I think China’s future might depend on its rural areas.”

In 2012, Wang became the first Chinese architect to win the prestigious Pritzker Prize. The jury praised Wang for his “unique ability to evoke the past without making direct references to history.”

Over the past seven years, Wang and his wife, architect Lu Wenyu, have focused their attention on China’s villages, many of which harbor the last examples of fading architectural traditions. As rural towns decline amid urbanization, Wang and Lu have worked to preserve their traditional architecture and lifestyles through village renovation projects. Their first project is Wencun, a village of 1,800 people in eastern China’s Zhejiang Province.

From country homes to skyscraper apartments, living space shapes lifestyles. But Wang takes this concept a step further. He believes reviving traditional architecture is a way to reconstruct cultural identities – and rediscover paths to our lost homes.

Back to the Country

A two-hour drive from Hangzhou, Wencun village is nestled in a small mountain range. A creek cuts the village in half. The left bank is lined with traditional stone cottages, while the right is dotted with newly built villas, Western-style houses and village administration buildings. Village committee chief Shen Zhanghai told NewsChina that since the 1980s, residents of Wencun have been tearing down their old houses to build new ones on the other side of the creek.

Many ancient buildings were left in disrepair. The village’s largest ancestral temple was overgrown with weeds. The village once had four town halls where villagers gathered and discussed local affairs. Today only one remains. While Wencun’s oldest existing buildings date back to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), it still is not officially registered among the country’s historic villages.

Together with students from the China Art Academy, Wang conducted research in Zhejiang Province. They found only one-tenth of villages were registered for cultural protection and around 27,000 villages were at risk of destruction. Wang refers to these neglected villages as “disabled.” “This is typical of China’s villages,” he told NewsChina.

Amateur Architecture Studio began restoring houses in Wencun using stone, bamboo and rammed earth. On the village’s western edge, Wang and Lu built 30 traditional courtyard homes. The buildings provide living space that includes a room for watching TV, a workshop, farm tool storage and shrines for ancestors and gods. Currently, 18 are residences and 12 are inns. Wang and Lu feature traditional Chinese elements in their designs. For example, every house has a tianjing, or square courtyard atrium. Roofed corridors enclose the courtyard, which blocks direct sunlight while providing ventilation during the hot summer. Tianjing literally means “celestial well” that according to feng shui principles is a portal that links heaven and earth, bringing good fortune to the household.

Initially, villagers were not keen on their tianjing, calling them old-fashioned and unnecessary. But attitudes quickly changed after they moved in. Villagers decorated their courtyards with potted plants and carvings, and added dining tables for entertaining guests. “We use our tianjing quite often,” one villager said. “It’s the perfect place for gathering and dining with friends and neighbors.”

“I hope these buildings create a space that implicitly lead villagers to revive traditional lifestyles,” Wang told NewsChina, adding that he hopes Wencun serves as a model for future village renovations.

When choosing projects, Wang said he often passes on villages registered as historic or cultural sites because they are already protected. He also does not choose villages near major highways. Once renovations are finished, they commercialize and develop quickly, which goes against the project’s intentions.

“The most urgent thing is to rescue old villages not listed for preservation and which are likely to be torn down,” Wang said.

Professional Amateur

Wang was born in November 1963 in Urumqi, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. He moved to Beijing as a child and spent four years living in the Beijing alleys, known as hutong, which date back to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The ancient capital’s labyrinthine alleys and the unique communities they created fascinated Wang.

He studied architecture at the Nanjing Institute of Technology (now Southeast University) and received his master’s in 1988.

Early on, Wang took a humble approach to architecture and developed strong interests in philosophy, literature and art. As an undergraduate, Wang retraced the route taken by writer Shen Congwen as described in his essay collection Random Sketches on a Trip to Hunan (1936). He spent three months visiting village after village, observing their unique cultures, traditions and architectural styles.

In 1988, Wang built his case against the status quo of Chinese architecture in his postgraduate dissertation “Notes From the Underground: The Poetic Construction of Space.”

Written in 15 days, Wang’s paper criticized the utilitarian trends of the time and declared his spiritual manifesto for architecture.

“The separation of thoughts and sensitivity has resulted in the loss of humanity and soul in architecture. It’s increasingly difficult to find spirituality in contemporary architecture,” Wang wrote. “As we madly strive to dominate our environment, we brutally murder the inner cosmos of the individual.”

The 1990s was a golden age for China’s architects. The human landscape of the country’s urban and rural areas underwent drastic changes in the torrent of reform and urbanization. Old buildings were being demolished and rebuilt everywhere.

Like many young architects, Wang chose Shenzhen to start his career. At the time, Shenzhen was a brand new city full of opportunity to strike it rich. But Wang left in 1992, a decision his peers at the time called unbelievable and foolish. Wang told his friends it wasn’t the time or place for architects like him.

Wang and Lu moved to Hangzhou, a city known for scenic natural landscapes and rich artistic traditions. The architect spent seven years working on construction sites, where he learned practical building knowledge straight from local artisans, masons and carpenters. In the meantime, Wang pursued his PhD at Tongji University in nearby Shanghai.

In 1997, Wang and Lu started Amateur Architecture Studio in Hangzhou. Wang explained the name is a statement against the “professional, soulless” designs of China and invokes the approach of an amateur builder: one based in spontaneity, craftsmanship and tradition.

Wang likes the harmony between human and nature portrayed in traditional Chinese art. He seeks to recreate the relationship through architecture in order to preserve Chinese culture, aesthetics and traditions as globalization takes hold.

“Architecture remixes city, buildings and nature with poetry and art into an inseparable, unclassifiable, integrated unity,” Wang wrote in his 2016 essay collection Building House.

Architect Wang Shu

Wang Shu and his wife, architect Lu Wenyu, launched their first village renovation project in Wencun, Zhejiang Province

Like the Moon or Mars

From Wang’s perspective, there are two kinds of architects: those who do not value the past and history, and those who do. When taking on projects, Wang and Lu said they consider history, memory, craft and location.

Amateur Architecture Studio designs often use recycled materials such as ceramic brick and tile fragments. The element is inspired by wa pan, a traditional building technique originally from Ningbo, a city on the coast of Zhejiang Province.

In the past, farmers would recycle fragmented tiles, bricks and ceramics to repair their homes damaged in summer typhoons.

For example, Wang found more than 80 different materials from different eras in a wall of a small Ningbo home. Even ceramic shards and chips were cemented into the wall façade. Wang said wa pan is a way to ensure the continuity of the region’s history in new construction.

Two of his signature works, the China Academy of Art’s Xiangshan Campus in Hangzhou (completed 2007) and the Ningbo Museum (completed 2008), epitomize his architectural philosophy. In both buildings, Wang used locally recycled materials – tiles, bricks, stones and ceramic fragments from demolished houses – and combined modern technology with traditional crafts.

Two million tiles went into the China Academy of Art’s Xiangshan Campus. Most of the Ningbo Museum’s exterior is covered with debris collected from nearby demolished structures, such as roof tiles and cement-covered bamboo.

Wang receives many invitations to take on projects but rejects most of them.

“They wipe out all the traces of human activity of a place, tear down everything, turn it into flat ground, and then start a new project. It’s like treating the Earth like the Moon or Mars. It’s an act that shows nothing but the lack of respect for our past and human history,” Wang said.

Old Version

Old Version