Yu Xuntan, the writer and poet best known by his pen name Liu Shahe, died on November 23 from throat cancer. He was 88.

Liu lived on Hongxing Road, a busy street in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. Locals usually saw him out strolling or buying food. He had a distinct walk with a delicate, almost ethereal gait. Liu once described himself as a “long, shriveled bean fluttering in the autumn wind.”

Every week, he would gather with the local literati: poets and writers, retired editors, reporters and lovers of literature. They would drink tea and chat – sometimes debate – about culture and current affairs. Liu was famously outspoken and never shied away from talking about his past. “His big mouth had gotten him in trouble since 1957, but he still wouldn’t shut up,” Wen Zhihang, a writer and regular at these gatherings, wrote in his essay “Liu Shahe in My Memory.”

In 1957, a 25-year-old Liu and three others co-founded the monthly poetry magazine Stars. Two weeks later, Liu faced criticism for a series of his poems in the magazine’s first issue. The series, “Plants,” is marked by a defiant voice that yearns for freedom.

“She has no will to flatter her master with flowers, and instead wraps herself with thorns,” reads one of the poems, titled “Cactus.” “Her master throws her out of the garden and cuts off the water. In the wild, in the desert, she lives, and she procreates…”

He was eventually labeled a rightist in 1957 and forced to work in the Sichuan countryside. During these difficult years, Liu found solace in the philosophy of ancient Chinese thinker Zhuangzi (476-221 BCE). Liu named his son Yu Kun after the opening line of Zhuangzi’s celebrated essay “Carefree Wandering” (Xiaoyao You): “In the Northern Ocean there is a fish, the name of which is Kun.” The free and independent spirit of Zhuangzi’s work provided Liu with the fortitude to persevere.

Over the last two decades, Liu went from poet to scholar, devoting himself to the research of traditional Chinese characters and culture.

“As a poet, Liu Shahe had a free and independent spirit, while as a scholar, he harbored a strong responsibility to promote cultural heritage,” Yan Jiafa, poet and co-editor of Stars, told NewsChina. “Throughout his life he suffered misfortune and humiliation, but he overcame all adversities.”

Born into a land-owning family in 1931 in Chengdu, Liu became a professional writer in 1952. Five years later, his family background, combined with his controversial poetry series “Plants” in Stars, condemned him to a hard labor camp in Jintang County in Sichuan. Liu worked for nearly two decades with cleaving saws and hammers, nailing together wood crates.

Liu’s son Yu Kun was born in 1967, who Liu said in his memoirs “didn’t come at the right time.” The tumult of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) had begun, and Liu’s label as a rightist posed a greater threat to his family.

Yu witnessed first-hand the hardships his father suffered. Six-year-old Yu helped his

father toil in the labor camp. The father and son would have to carry powerline poles on their shoulders.

“In the beginning, the poles were made of wood, but later we carried the ones made of cement,” Yu Kun told NewsChina.

Hunger and malnutrition made the years even more intolerable. “The family only had pickled vegetables to eat. We were starving almost every day. We’d usually tighten our belts when we felt hungry, and it really worked. But over time I gradually got varicose veins on my abdomen,” Yu Kun said.

For almost six years, the father and son sawed thick, wide logs at a furniture-manufacturing commune.

“I had to steel myself instead of letting others saw me into sawdust. So I had to work like hell. Fortunately, my family still had three hens and they laid eggs every day. I wouldn’t let myself die of starvation just when dawn was about to break,” Liu wrote in his 1988 memoir A Record of Saw-Tooth Scars.

Liu writes how in 1962 he took out most of his life’s work – manuscripts, diaries, letters and notes – gave it a final glance, and burned it. “It took entirely one hour to burn the first half of my life,” Liu wrote.

He later revisited the experience with bitter humor in a short poem “Burning Books”: “Neither can I save you, nor hide you. This night, into the furnace I throw you. Farewell, Chekhov. With a pince-nez and a goatee, you’re smiling while I weep. Burn to ashes, both you and the light. Farewell, Chekhov.”

Over the course of the Cultural Revolution, paramilitary units of Red Guards raided Liu’s home 12 times to smash anything they deemed feudalist, capitalist and revisionist. They confiscated more than 600 books Liu had collected.

He Jie, Liu’s wife, hid Liu’s few remaining manuscripts by weaving them into her underwear and their children’s infant clothes.

Liu continued to write during the Cultural Revolution. He would jot down poems, silently memorize them and burn them afterward. It would be the 1980s before they saw the light of day. Many of the poems he wrote during the Cultural Revolution were colloquial, had a light rhythm and local color. Emotionally, they are a mixture of pain, desolation and sweetness. Liu’s house had a bleak front yard. In it, he built a low fence and planted a patch of bamboo, which would attract chirping crickets in the summer. Liu remembers catching crickets with his children in the short poem “A Night Catch”:

“My children dragged me to the garden at night to catch crickets under the hedge. Quietly we stepped, breathlessly we listened. My little daughter held a bottle, my little son a lamp. Eight or nine crickets we caught in all. There was no more singing in the bleak garden. Look back at what we had in the bottle: painful insects, broken legs, so sorrowful and lonely.”

The Cultural Revolution ended, and in 1978, Liu’s rightist label was removed. One year later, he returned to Stars, where he helped promote writers and poets, including the late Yu Kwang-chung.

The 1980s was a golden age for poetry in China. Poets were like rock stars, idolized by young people eager to embrace the idealism, freedom and liberalism in their works. Liu was among those celebrated, and his young fans would travel across the country to Chengdu for a glimpse of Liu and Bai Hang, another poet and co-founder of Stars.

Yan Jiafa recalled a running joke at Stars about the waves of fans: “We should run our editorial office like a zoo: We should just lock our poets inside and sell tickets to see them.” Throughout the 1980s, Liu devoted himself to poetry and editing. Now in his 50s, Liu wrote more with a tone of sentimentality and sense of irretrievable loss over his youth.

“Six Love Poems,” “Dreaming of Xi’an” and “Butterfly” are records of the emotional solace he found during his most difficult years. Other titles, such as “Nine Odes on My Hometown,” are more jocular and self-mocking.

Liu was known as a very meticulous editor. “He had a deep obsession with words and was the ‘encyclopedia’ of the editorial office. Even if a poem had been edited thoroughly and proofread several times, he still could find problems,” Yan said.

Liu also devoted himself to introducing and commenting on modern poetry in Taiwan, publishing the books Twelve Taiwan Poets and Talking of Poetry Across the Sea.

By the end of the 1980s, Liu had stopped writing poems. He realized the times had changed. The luster of poetry had dimmed as the country strode toward commercialism and consumerism.

“Many years later, my father told his friends in private that at that time, he re-examined the role of poets and his own place in society. He realized that many things were difficult to express precisely in poetry,” Yu Kun told NewsChina.

In the last two decades of his life, Liu focused on researching Chinese characters and ancient Chinese culture.

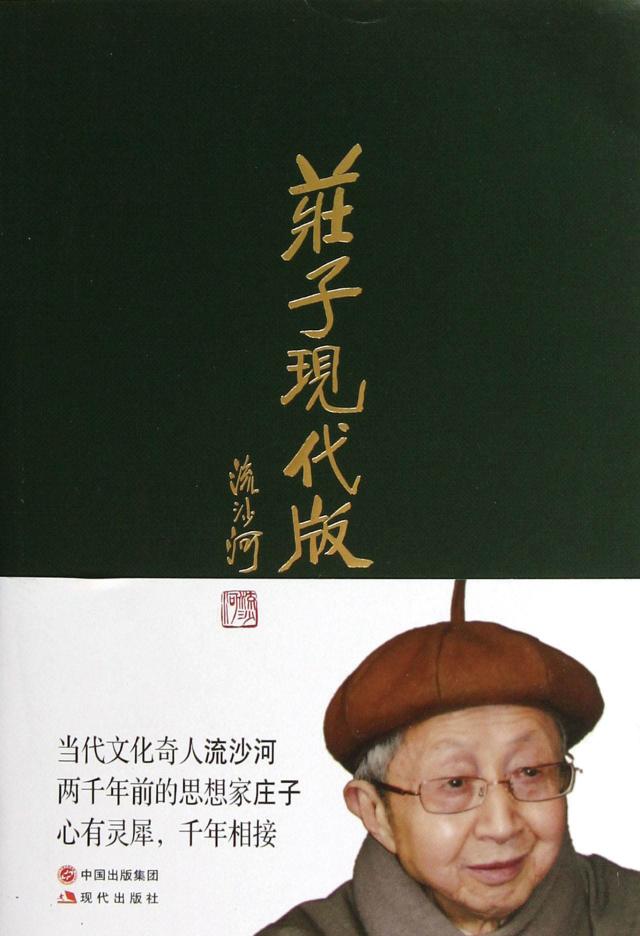

Zhuangzi: A Modern Version, a collection of the philosopher’s essays Liu translated into modern Chinese, was published in 1992.

Since 2009, Liu held public lectures at a local library on ancient Chinese philosophy and literature, including Zhuangzi, The Book of Songs and Tang Dynasty poetry. The heavy workload worsened Liu’s throat, but he cherished the job and saw it as a way to make his voice heard.

“He once said that though he was living in modern times, he had the heart of an ancient man,” Yan said. “He researched characters, dialects and traditional culture, and was very willing to share his findings and learning with everyone. No matter how fast things were changing, he was devoted to creating a garden of culture accessible to anyone.”

After Liu passed away on November 23, literati and internet users across China expressed their grief.

“Liu’s life was full of twists and turns, but after having undergone so much suffering, he had understood his true life mission – to write honestly and always stay true to himself, and provide us with a pure and clean literary haven,” wrote Liang Ping, former chief editor of Stars and vice president of the Writers Association of Sichuan Province, in his eulogy to the poet.

Old Version

Old Version