In the past few years, as disputes over the South China Sea between China and several Southeast Asian nations have escalated and become one of the most prominent issues featured in the global media, some simplistic narratives regarding the issue have been established, apparently intended to offer readers an abbreviated primer on an otherwise very complex issue. But, as is so often the case with the coverage on China and its foreign policy, many of these narratives can be partial, biased and even purely mythic. This month, NewsChina aims to disprove three myths regarding China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea that have been persistently recycled by the international press.

Myth 1: China claims 90 percent of the South China Sea as its territorial waters.

This is perhaps the most overused statement in international media reports describing China’s claims in the South China Sea, and helps to project China as an expansionist country overreaching itself. But the reality is that China has never officially claimed the South China Sea as its territorial waters.

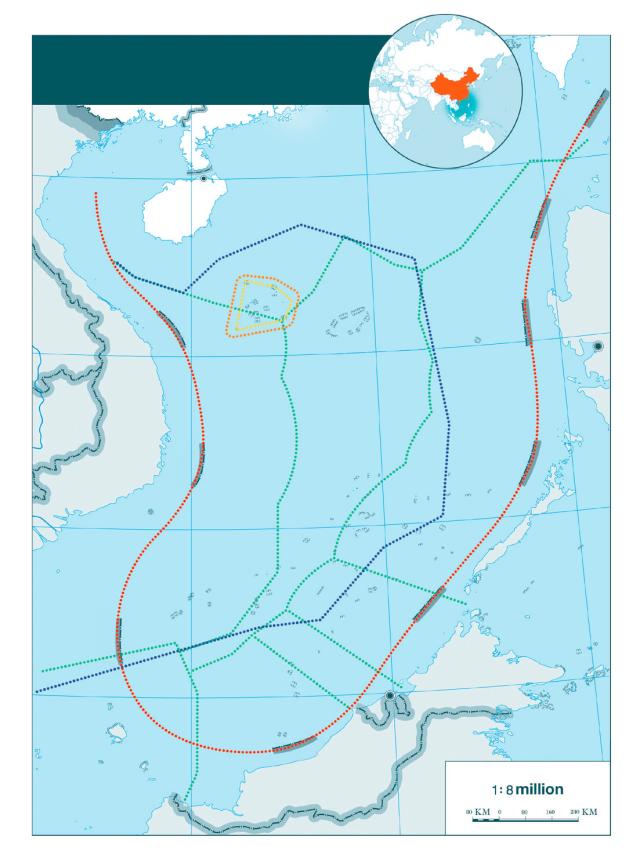

Amid the disputes over the South China Sea, the US has consistently urged China to clarify the status of the so-called “nine-dash line,” based on a map of maritime boundaries published by the government of the Republic of China in 1947, which laid the foundations for China’s current claim.

China has equally consistently refused to clarify the legal meaning of the nine-dash line, a decision that has drawn criticism from both abroad and within China. Many argue that the failure to stake an official claim is a sign that Beijing does not intend to follow international law in handling its maritime disputes. The false assertion equivocating China’s nine-dash line with a territorial boundary may reflect such concerns.

In fact, there are various signs that China does not consider the line as a demarcation of its territorial waters. According to Wu Shicun, president of the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, China does not consider the line as a territorial boundary, but claims whatever rights are associated with the islands, reefs, shoals and rocks that fall within the nine-dash line, a remit that would include territorial waters, exclusive economic zones or any other maritime rights permitted in international law. Wu estimated that, in their entirety, these rights would cover 60 percent of the South China Sea, rather than 90 percent.

As Wu has co-authored a lengthy article entitled “South China Sea: How We Got to This Stage” with Fu Ying, a spokesperson for the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s parliament, which was published in China Newsweek on May 16, his argument is often considered semi-official. Moreover, China declared a territorial baseline around the Xisha (Paracel) Islands in 1996, an indirect indication that China did not consider the nine-dash line as demarcating its territorial waters.

So why does China continue to refuse to clarify its claims regarding the nine-dash line? Western experts tend to consider the government’s silence proof of China’s intentions to make “excessive” claims that increase alongside its ability to project power within the region. But there are alternative explanations. For example, many in China argue that it is an act of restraint. Given rising nationalism in both China and other countries, once China makes official claims, it might find itself without any room to maneuver at a future negotiating table.

Others argue that China considers the request to clarify its claims an attempt to undermine a position it has stated with absolute clarity: that the disputes should only be resolved between countries that have territorial claims in the region.

One can continue to criticize China’s insistence on vagueness, but while criticizing and refuting China’s claims is one thing, exaggeration and presumption is another.

Myth 2: China’s claims in the South China Sea are mainly based on “abstract” and “ancient” precursors.

Such a statement, often combined with an emphasis on China’s recent “aggression” or “assertiveness” in its maritime disputes, depicts a picture of an expansionist China seeking to revive the imperial glory of its distant past by projecting its more recently acquired military power.

Given general familiarity with the rise of Western imperialism and colonialism in modern history, which saw the collapse of pre-industrial states and unfurled a new geopolitical map of the world, mostly at the expense of declining historical powers such as China, the emphasis on China’s historical claims in the South China Sea can often lead outsiders to ridicule Beijing’s stance.

China’s modern-day claims in fact go well beyond citing ancient history. Chinese academics and strategists argue that it is the Chinese who first discovered, named and administered the islands in the South China Sea, and have presented historical records to that effect.

China has also stressed that its jurisdiction over the region continued well into the modern era. In particular, China has emphasized that its sovereignty over the South China Sea was endorsed by post-World War II international settlements, something consistently ignored in Western media coverage of present-day disputes.

It was the Asian encroachment of Western colonial powers and the rise of Japan that undermined China’s previously uncontested sphere of influence in the South China Sea. In the 1930s, some islands in the South China Sea were incorporated into French Indochina, and Japan occupied many more during its advance into Southeast Asia in World War II. China argues that these were “brief interruptions” of Chinese sovereignty, and points to various documents signed by Allied leaders, including the Cairo Declaration of November 1943, which state that all the territories Japan seized from China should be restored to China as part of the postwar settlement.

It was based on this principle that the then Nationalist government of China sent warships to occupy Taiping (Itu Aba) Island and Zhongye (Thitu) Island in December 1946. In 1947, the Nationalist government renamed a total of 159 islands, islets and sandbanks and published a map of China’s maritime boundaries, a precursor to the map of today’s nine-dash line.

It is beyond doubt that China’s claims are disputed by other claimants.

But, once again, there is a fundamental difference between refuting China’s claims and misrepresenting the basis for them.

Myth 3: With the exception of China, other countries’ claims in the South China Sea are based on their exclusive economic zones (EEZs).

Following on from the argument ridiculing China’s “abstract, ancient” claims, Western coverage of the South China Sea disputes often leaves readers with the impression that other countries have better claims, more firmly grounded in legal precedent, than China does.

But the assertion that other countries base their own claims entirely on their own EEZs, or the bands that extend 200 nautical miles from

their shores, is partial and misleading. While this logic generally applies to the respective positions of the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Brunei, Vietnam is a major exception.

Vietnam claims both the Xisha/Paracel and Nansha (Spratly) islands in the South China Sea, though only a small portion of the Xisha/Paracel archipelago falls within 200 nautical miles of Vietnam’s coast. Contrary to popular perceptions, the majority of the Xisha/ Paracel island chain lies within 200 nautical miles of China’s Hainan Province.

For example, Yongxing (Woody) Island, the largest landmass in the Xisha/Paracel group, is about 300 kilometers (162 nautical miles) off the Chinese coast, and about 400 kilometers (216 nautical miles) from the Vietnamese coast. The Nansha/Spratly Islands are even further removed from the Vietnamese coast. Taiping/Itu Aba Island, the biggest in the group, is 580 kilometers away from Vietnam’s coast, far outside its EEZ.

Some may argue that Vietnam is just one of the five Southeast Asian countries that have a claim in the South China Sea. However, considering Vietnam’s disproportionate prominence in the recent disputes, the international media’s adoption of a “China vs. everybody else” approach regarding the legal basis for competing claims can seriously occlude the complexity of the disputes.

Vietnam is the only country locked in a dispute with China over the Xisha/Paracel Islands, which China has controlled since 1974, and is the country that has occupied the most islands and reefs in the Nansha/Spratly archipelago, an estimated 29 islands and reefs, more than the combined number occupied by all other parties, including China. By comparison, China only controls seven islands and reefs in the Spratly chain.

To some extent, Vietnam’s claims over the South China Sea are similar to those made by China. Hanoi argues that it was the Vietnamese, not the Chinese, who first discovered and occupied the islands. As a former French colony, Vietnam also considers France’s brief occupation of some of the islands in the 1930s a historical legacy it should inherit, and argues that it is Vietnam, not China, that should have been the legitimate administrator of the islands after they were liberated from the Japanese.

Therefore, it is incorrect to cast China’s claims as purely historical and all other players’ as EEZ-related. It might have behooved the international media to bundle China and Vietnam together instead of setting China up as sole antagonist. The China versus the world perspective adopted in discussion of the South China Sea also fails to distinguish between the quite separate legal disputes over the status of the Xisha/Paracel and Nansha/Spratly chains. While most of the Xisha/Paracels falls within China’s EEZ and has been under firm Chinese control for more than four decades, the Nansha/Spratlys have been carved up by various countries.

Only by understanding the difference between the two disputes can one understand the rationale behind recent exchanges between China and the US. As the US expanded its freedom of navigation operations from the Nansha/Spratly chain to sail within 12 nautical miles of islands in the Xisha/Paracels, it is not surprising that China considered the move an escalated provocation. In response, China has deployed advanced air defense systems and a J-11 fighter jet squadron in the South China Sea, basing both forces in the Xisha/Paracels. China has, however, refrained from making major military deployments in the Nansha/Spratlys.

While one may speculate over why the Western media has generally failed to offer a more complete picture of the dispute, it is understandable why the perpetuation of the above myths has been interpreted as an attempt to single out China as a particular threat.

To a large extent, a major reason the disputes have continued to escalate can be attributed to such myth-making on all sides of the argument, as misinformed people and decision-makers may seek to take action to exacerbate an already strained situation.

Avoiding oversimplified, shorthand narratives might make for a slower news day, but it would also create a better informed basis for debate and a less politically charged atmosphere in which the US and its allies can engage with China over this contentious issue.

Old Version

Old Version