Zhang Xiaolei did not sleep easy in Beijing until she and her 12-yearold son Zhao Ze moved to a small windowed room near her child’s “dojo.” Both mother and son had spent the previous month in a rented basement apartment, so damp that Zhang was constantly sick.

On February 29, Zhang had accompanied her son to Beijing to begin his formal training in Go, one of East Asia’s most revered traditional board games that recently shot to fame when a Google-developed Go-playing computer program beat a global grandmaster at the game.

Zhang told NewsChina that her son had shown a gift for Go since the age of four, adding that she hoped that enrollment in a Go dojo would help her son win the upcoming annual playoffs, clearing the way for entry to a career as a professional Go master.

Zhao is just one of several hundred children who have been pulled out of school and relocated to the capital to train at Go.

Despite the hot-housing, few will manage to turn professional and join China’s national team. Even after witnessing thousands of youngsters crash out during the annual playoffs, described by some as more cruel and demanding even than China’s notorious college entrance examination, the gaokao, parents continue to walk the same path, driven by a heady mix of ambition, pride, hope and concern.

Migration When Zhao Ze arrived in Beijing, Gao Wenxuan, a nine-year-old player from Chengdu, Sichuan Province, had already been studying in the Geyuhong Dojo for over two years. Like Zhao, he showed a strong interest in Go from the age of four, and his local master suggested that his parents send him to Beijing for further study.

Gu Ying, Gao’s mother, told NewsChina that her son had reached the rank of amateur fifth dan, an achievement which indicates national-level ability. Going to Beijing, she reasoned, where the greatest concentration of top Go schools and masters can be found, is the only way gifted children can make further progress. Ke Jie and Fan Tingjue, the two youngest Chinese Go champions, for example, both studied in Beijing dojos.

The capital’s Go dojos are as well known for their high-intensity courses and strict disciplinary policies as they are for their superior staff. Geyuhong, one of China’s top four Go schools, requires its students to study and practice Go for up to 10 hours a day, arranging games of Hayago, a speedier version of the game, on the weekends. In 2009, one year after its founding, Geyuhong saw 14 students awarded amateur fifth dan rankings.

In 2014, Geyuhong became China’s biggest Go school after merging with another facility established by grandmaster Nie Weiping.

Since then, it has only enrolled students of amateur fifth dan rank or above. Last year, Geyuhong merged with yet another school,expanding its faculty to 120 professional Go masters. The school’s namesake and founder, Ge Yuhong, has since split the school into three tiers of study, with the uppermost only accessible to the top 66 students.

“Superior resources are concentrated here.

Tier-one classes are equivalent to high school prep classes for entry to top universities,” Ge told NewsChina. According to him, the school’s 100-some students are aged from nine to 18, and most of them hail from outside Beijing. “The students in our long-term classes used to be boarders, but now 75 percent of them live off campus, accompanied by their parents, usually their mothers,” he said.

Gu Ying is one of these “Go mothers.” She told our reporter that she initially applied for short-term training for her son, since she felt that nine hours of constant daily study was too harsh to inflict on a seven-year-old child, but her son told her that he likes his classes.

They then stayed on in Beijing, and her son embarked on long-term training.

Sheng Qing, the mother of another student, has remained in the capital with her daughter Li Yao for five years. Li’s Go ability also revealed itself at age four, and she too was advised to relocate to Beijing by her teacher.

“Her grandparents would have rather she went to a good college and on to a good job just like other girls, but I told them that we should give her Go gift a chance, or be resented by her later in life,” said Sheng.

Sheng found a job in Beijing and enrolled Li, then about nine years old, in Geyuhong.

In order to take better care of her daughter, Sheng later quit her job, a gamble that led her to issue her daughter with an ultimatum.

If Li could earn an amateur fifth dan ranking within two years, her mother stated, they would stay in Beijing for further training.

If Li failed, they would go back home and she would return to her formal education.

“In two years’ time, she would be old enough for middle school, and I believed that I could homeschool her to make sure she was caught up on the last two years of elementary school,” Sheng explained.

Li failed to reach the fifth dan within the time limit, and went back to school. In her mother’s view, the mathematical and logical thinking skills she developed during her Go training made Li perform well in every school subject, except for English. However, the girl told her mother that she did not want to abandon Go. Once again, Sheng pulled her daughter out of school and returned to Beijing. “Once you set out on this road, it is hard to stop midway. You will always convince yourself to try again,” she told News- China.

Costly In 2012, Li Yao participated in the national playoffs for the first time, but was knocked out in the qualifying round. The next year, she made it to the quarterfinals, but failed to place in the top 60. Her struggle was looking increasingly desperate – with only five places set aside for professional female Go players, Li’s dream of making the big leagues was slipping away.

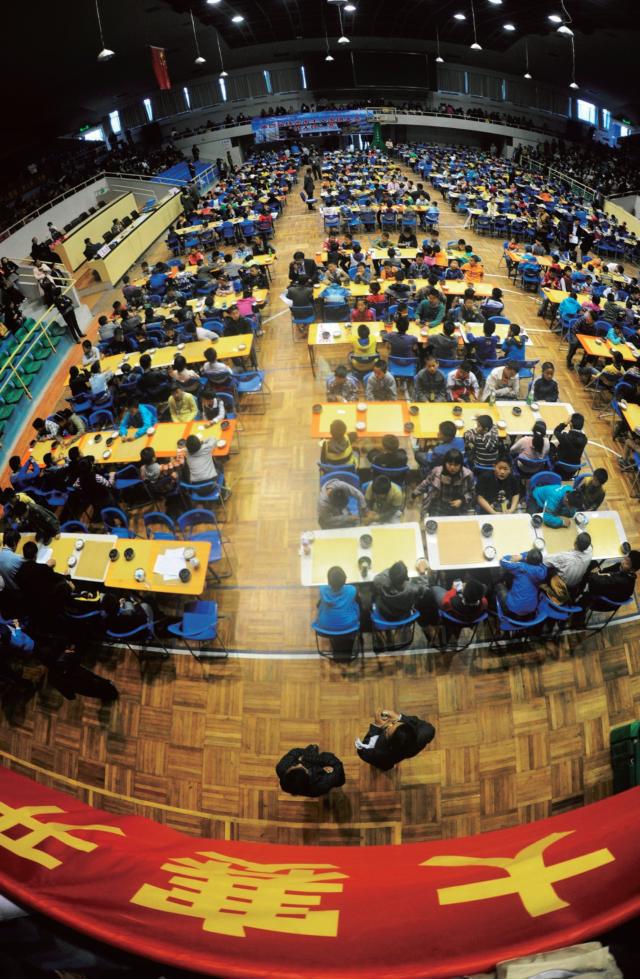

Meanwhile, both Li and her mother were under mounting pressure. Unlike gaokao candidates who can choose to apply to any of China’s several thousand universities, Go children have only one path to success – the national playoffs and the professional league. With only 25 new places up for grabs each year, 20 of which are for men only, the odds are massively stacked against even the most talented hopefuls. In 2013, 555 candidates competed in the playoffs, meaning an “enrollment rate” equivalent to 4.5 percent.

That same year, the 74.3 percent of gaokao candidates were admitted to a post-secondary institution.

Anything less than 100 percent commitment from a candidate, therefore, is unacceptable.

Zhang Xiaolei told our reporter she spent several days being furious with her son after she discovered he had secretly played a game of soccer after class. “He kept apologizing, but I did not want to forgive him. Why did we come here? If he can’t concentrate his efforts on Go, this is a total waste of time,” she told NewsChina.

“If our money runs out someday, we will have to leave, no matter how much we want to stay,” she added.

According to Zhang, nearly all her family members and relatives are chipping in to support her and her son financially. Even so, she can only afford to pay her son’s tuition month-to-month. Even when they were living in their damp basement apartment, she still had to spend 10,000 yuan (US$1,539) in their first month in Beijing. Her son’s monthly tuition had eaten up 4,000 yuan (US$615). This amount is almost equivalent to the average monthly salary in Zhang’s hometown in Henan Province.

“I have given my son half a year of ‘probation,’” she said. “If he makes the quarterfinal of this year’s playoffs, or is moved up into a more advanced class, we stay. If he fails, we leave. We can’t afford the training indefinitely.

We have to fight and win, or die.” Gu Ying has also pinned everything on her child’s Go skills. She told our reporter that she has spent around 180,000 yuan (US$27,692) per year. In addition to rent, tuition and daily expenses, she also hired a private tutor to homeschool her son in some of the subjects he was missing out on in his dojo, which cost her an additional 2,000- 3,000 yuan (US$308-462) per month.

Like Zhang Xiaolei, Gu is very strict with her son, Gao Wenxuan – she only allows him an hour of TV at a time. If Gao asks to watch for longer, she has a simple response: “Think of your dream.” “I have been his alarm bell, because children like him should have a sense of urgency,” she explained.

In his two years in his dojo, Gao has steadily moved up the rankings, encouraging his mother but also raising the stakes. “If my son gets into the top two tiers, I will hire a leading professional player to give him additional tuition. This is a common practice in the dojos,” Gu said. “However, that will cost around 1,500-2,000 yuan (US$231-308) for a two-hour session. Many parents are smart enough to not go to Beijing, since, without enough money, they cannot offer a good living or study environment for their children.” Dilemma According to Gu, she was quietly supportive of Gao’s study of Go at the very beginning.

“It was just a hobby,” she said. “Since I don’t trust the Chinese education system very much, I don’t think it a big deal to quit school. Instead, I believe that it is more important for a child to specialize in something – like Go.” After her seven-year-old son broke down in tears after losing an important game, however, Gu’s view of her son’s passion gradually changed.

“I did not understand why he took a game so seriously,” she said, adding that all she can do after his losses is comfort him. “We both become stronger. The games are too cruel. Sometimes, my son also feels sad if he beats someone older than he is,” she said.

As received wisdom maintains that as children age, their ability to evolve into Go prodigies diminishes, all Go parents and their children feel they are fighting against the clock. Now 14 years old, Li Yao is rapidly losing hope. “Starting about two years ago, I began to rethink my decision to bring my daughter to Beijing a second time,” her mother told NewsChina. “By now, she could have been performing well in high school. But we’ve been stuck in rented houses in Beijing for five years, moving around all the time. It is pointless,” she continued, adding that if her daughter still fails to qualify in the playoffs at 15, she will take her back home and enroll her in high school.

While pulling their children out of elementary school is an easy decision for most Go parents, as their children get older and continue to fail to qualify in the national playoffs, the financial, academic and social pressures to return home begin to pile up.

Parents gradually come to realize they have taken a gamble, and as the odds tilt ever more against them, it becomes harder and harder to stand by their decision to pin their family’s hopes on incubating a national Go champion.

“I often feel sorry for my son,” said Gu Ying.

“He should have had a happy childhood like other kids do. Instead, he has had to study Go for over nine hours a day and attend matches and competitions all over the country. We, his parents, also missed the chance to grow up with him. We have turned a hobby into a bitter, zerosum game.” Sheng Qing feels similarly. “I never used to care when my daughter lost a game, but now, her failures cause me to lose sleep and focus,” she said. “We have to win. Who doesn’t want to win? It is like all the Go children are trying to cross one single-log bridge – if we don’t make it across, we’ll be trapped.” “Even if we make it across, we will still face a lot of challenges,” she went on. “We have lost too much – jobs, money, even ourselves… My family is split. My husband is living alone and working in Nanjing. But what else can we do?

All we have is here! If a parent asked me now whether or not they should send their children to Beijing [for Go training], I would tell them ‘no.’” Hang Tianpeng, president of the Hangzhou Go School, understands the dilemma many ambitious parents of Go children face. Even returning to regular school life is difficult for children taught to do nothing but play Go for 10 hours a day. “I hope parents and their children consider their Go dreams more carefully. Think how many children will finally make it to that peak. If your child fails, he or she may also lag far behind in mainstream education.”

Old Version

Old Version