The increased demand for mineral resources that is driving commercial mining in the world’s ocean floors continues to strain global negotiations on exploration and exploitation of seabed resources. NewsChina investigates

In late July, at the International Seabed Authority (ISA) headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica, delegates from over 160 member countries gathered to discuss the future of global deep-sea mining.

Outside the venue, around a dozen people gathered for a few hours of peaceful protest. There were no police. A large yellow banner from Greenpeace summed up their message for the ISA: “No deep sea mining.”

But perhaps more poignant – and worrisome – was the contrast in turnout. Conflict over environmental concerns and global demand for deep-sea resources have escalated in recent years as the world moves from exploration to exploitation of seabed resources.

However, compromise could come too late. According to Louisa Casson, oceans campaigner with Greenpeace International, deep-sea mining comes with unavoidable and potentially irreversible harm to the oceans. Looming threats include extinction of unique species, hindering the ocean’s ability to limit climate change with stored blue carbon in deep-sea sediment, and undermining food security for billions of people.

“The ISA illustrates the problems with the fragmented governance of international waters, which is driving the health of the global oceans into crisis.” Casson told NewsChina.

Digging for Compromise

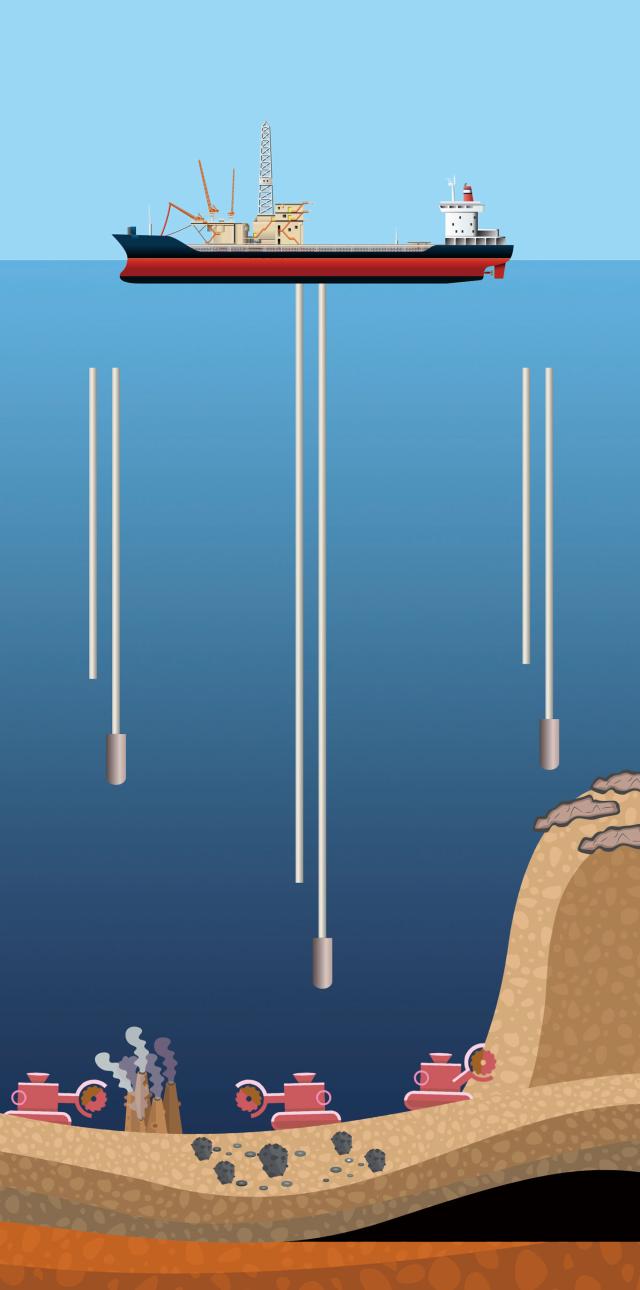

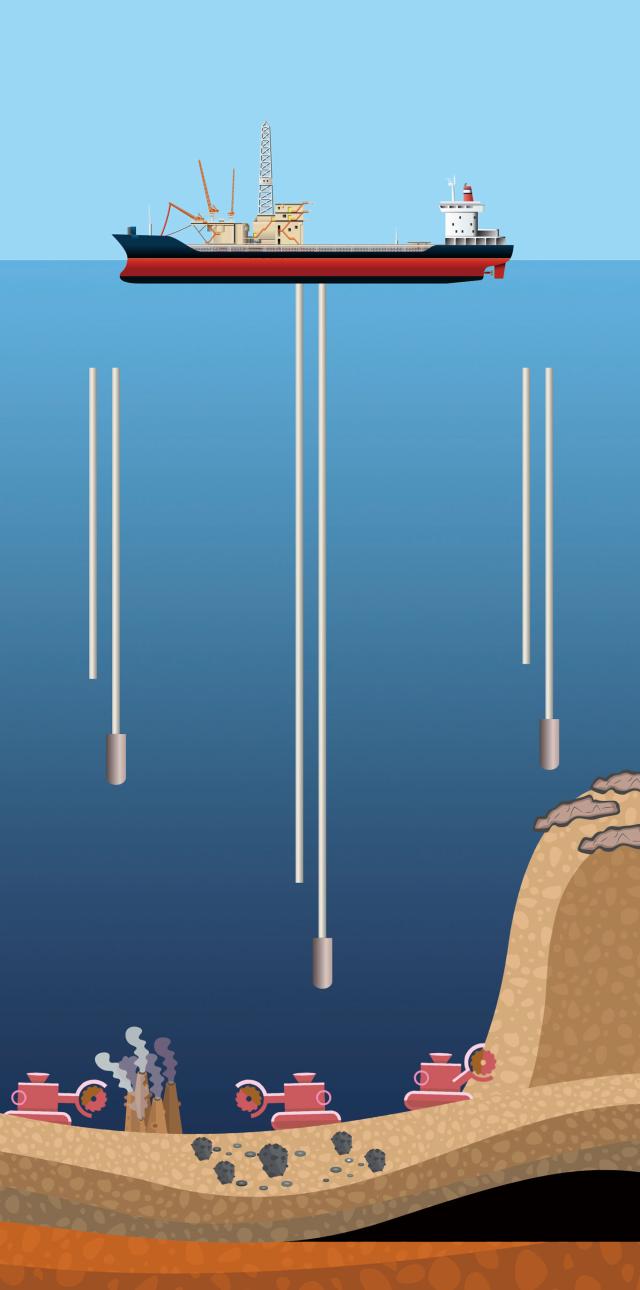

The term deep seabed refers to the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction that makes up around 60 percent of the Earth’s surface. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the international deep seabed area and its resources are “common heritage of humankind” and free from the claim of any state. Since the late 1970s, the world turned its eyes to undersea mining, a process to collect minerals from the bottom of the ocean by essentially vacuuming the minerals off the sea floor.

There are three major types of deep-seabed mineral resources: polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulfides and cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts. Polymetallic nodules were first detected on the ocean floor during an expedition by the British vessel HMS Challenger in 1873. Found on the sea floor or partially buried in the seabed, nodules contain metals such as cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese. Technology for locating polymetallic nodules boomed in the 1970s and 1980s. According to Liu Feng, secretary general of the China Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association (COMRA), countries such as the US collected over 800 tons over that period.

Liu told NewsChina that the sharp spike in global oil prices during the 1970s fueled exploration of seabed mineral resources.

In the late 1990s, two more valuable mineral resources were discovered: polymetallic sulfides and cobalt-rich crusts. Polymetallic sulfides form around hydrothermal vents in volcanic areas of the seabed and contain copper, zinc, lead, silver and gold. Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts accumulate on seamounts and seabed rocks and contain cobalt, copper, nickel, molybdenum, and rare earths.

The ISA was set up under UNCLOS in 1994 to regulate and govern seabed mining and encourage sustainable development of mineral resources to balance demand and environmental protection.

UNCLOS emphasizes that activities in areas authorized for exploration and exploitation by the ISA, referred to as the Area, must benefit all humankind, and take “developing states’ interests and needs” into special consideration. Financial and other economic benefits gained from activities in the Area must be “equitably shared” on a non-discriminatory basis.

Also according to the Convention, no country or person can explore or exploit mineral resources in the deep seabed without a stringent contract from ISA. This means deep-sea mining contractors are required to share any gains from mining activities, from the monetary to technological. So far 167 countries have ratified UNCLOS and become ISA member states. The US is an exception.

According to UNCLOS, potential investors or contractors that wish to mine mineral resources in the Area must be subject to the regulation of the ISA.

At the application stage for polymetallic nodules, the applicant should set aside a reserved area from its application area for ISA with “equal estimated commercial value.” In its first few years, the ISA worked to regulate prospecting and exploration of marine minerals in the Area.

The ISA completed exploration regulations for all three mineral resources in 2012. Ever since, the ISA has focused on developing regulations for exploitation, financial distribution of benefits among countries, commercial benefits for contractors and potential environmental impacts on marine biodiversity.

The ISA has issued 29 contracts to companies and State agencies from China, South Korea, Japan, the UK, Germany, Belgium, France, Russia, Brazil, India, Poland and South Pacific countries to explore for metals in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian oceans.

Algerian delegate Mehdi Remaoun said during the recent ISA assembly that if not for the ISA, “the seabed would see a new form of colonization, with the interests of a few more important than the common good.” During a recent lecture, Stephen Vasciannie, president of the Jamaica University of Technology, said: “Developed and developing countries have historically had different views on seabed resources,” adding that “the ISA was a compromise, to ensure that the benefits derived from those individual states able to exploit seabed resources could be shared as a common heritage.”

The ISA also has its critics, who argue the authority prioritizes development over conservation. In an email interview, Duncan Currie, legal and policy adviser for the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, wrote: “The ISA secretariat has been far too involved in promoting seabed mining, actively arguing for its instigation, arguing that it is better than terrestrial mining.”

“The ISA was created under UNCLOS, so it is as effective as other UN conventions that require decision-making to be based on negotiations and involvement of all parties,” said Xue Guifang, professor of KoGuan Law School, Shanghai Jiao Tong University and ISA observer. “Two challenges remain for the ISA: potential conflicts of interest with land-based mineral resource producers and the unavoidable impacts of seabed mining on the marine environment,” Xue said.

“I don’t support criticism of the ISA from environmental NGOs, as UNCLOS itself required a balanced solution for both resource exploitation and environmental impact to share benefits globally,” Xue said.

China’s Role

Advanced technologies helped Western countries such as the US, Germany and the UK complete exploration for polymetallic nodules in the Area in the 1970s and 1980s. While China started relatively late, it has been active in global initiatives for setting up international maritime law, from the early stages of negotiations for UNCLOS to setting up the ISA. China ratified UNCLOS in 1996 to become an ISA member country.

In an article “China’s Efforts in Deep Sea-Bed Mining: Law and Practice,” which explores the history of China’s involvement in the ISA, author Zou Keyuan from the University of Central Lancashire wrote: “China believes the international seabed should be used for peaceful purposes. Its resources are jointly owned by the peoples of all countries and an effective international organization and mechanism should be worked out to manage and exploit those resources.”

China’s active role resulted in it becoming one of seven registered pioneer investors under the ISA administration. At the most recent ISA event in July, this reporter observed China actively taking part in both the council and assembly meetings, making significant contributions to negotiations on issues relating to deep seabed mining.

A member of the Chinese delegation said on the sidelines of the ISA meeting that in contrast to some countries who aim to speed up negotiations on exploitation regulations (according to the initial schedule, ISA set 2020 as the deadline), China has repeatedly cautioned the ISA to “take it step by step” in completing exploitation regulations for commercial seabed mining activities. The delegate, who asked not to be named, said China has also made significant financial contributions to the work of the ISA and fulfilling its contractor responsibilities to promote common heritage principles through training programs for professionals from developing nations. “Now ranking second in financial contributions to the ISA, China will take over Japan’s position as the number one member country sponsoring the ISA’s work,” the delegate said. Duncan Currie told NewsChina that “China has taken a constructive role. It consistently acts to promote the common heritage of mankind, argues for a financial model to include profit sharing and its consistent position has been there is no rush to go seabed mining.” So far, China has signed four contracts with the ISA for seabed resource exploration, with the fifth application just approved by the ISA Council.

Since the 1980s, China has made significant progress in developing its deep-sea scientific research and exploration of seabed mining resources. According to Liu Feng, COMRA has developed a series of underwater robots and manned submersibles. Since 1991, COMRA has overseen 55 voyages in the Area. To fulfill its obligations as an ISA sponsor state, China also adopted its domestic Law on Exploration for and Exploitation of Resources in the Deep Seabed Area. Taking effect on May 1, 2016, the law filled a vacuum in the country’s marine legal system and made China one of the few countries in the world with a national law governing seabed mining.

Zhang Dan, associate researcher from the China Institute for Marine Affairs, Ministry of Natural Resources and a participant in drafting China’s deep sea exploration and exploitation law, told

NewsChina that the law dedicates a chapter to environmental protection and stipulates specific penalties for marine pollution from seabed mining exploration activities. Besides peaceful utilization, cooperative sharing, environmental protection and common benefit, the law also emphasizes fostering international cooperation, Zhang added.

“China is setting up its role as a responsible country for international seabed resource governance,” said Zhang: “Apart from abiding by the common heritage principle, China has invested significantly in seabed exploration activities, sharing of its scientific achievements with other member countries through capacity building projects and other means.”

The Xiangyanghong No. 10 breaks the surface to install a CTD (conductance, temperature and depth) system 2,000 meters below the southwestern Indian Ocean

US Absence

Despite its pioneering efforts in the exploration of seabed mineral resources, the US has never ratified UNCLOS and is not a member state of the ISA. On July 23, Vasciannie stressed during his lecture that although UNCLOS has 167 member states, “the absence of the US is problematic,” adding it is “an ongoing conflict and a significant question in international law.” According to Zou Keyuan’s article, after the US failed to have its proposals endorsed by UNCLOS in the 1980s, it enacted its own domestic laws that allowed American companies to mine in the Area, arguing that “exploration for and commercial recovery of hard mineral resources of the deep sea-bed are freedoms of the high seas subject to a duty of reasonable regard to the interests of other states in their exercise of those and other freedoms recognized by general principles of international law.”

In June 1980, the US Congress enacted the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHMRA), which enables US citizens and corporations to apply for 10-year licenses to explore and 20-year mining permits from the Administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In his 2012 article “The US Can Mine the Deep Seabed Without Joining the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea,” scholar Steven Groves with The Heritage Foundation defends the US’s refusal to ratify UNCLOS, saying that doing so would put the US and its seabed mining companies under the regulatory power and control of the ISA, forcing companies to pay royalties to the ISA to be redistributed to developing countries.

The US continues seabed mining in the Area on claims that deep seabed mining is a high seas freedom open to all nations regardless of whether they are party to the Convention. “The nations that have joined UNCLOS cannot prevent the US or any other nation from mining the seabed any more than they can prevent the US from exercising the freedom of navigation and overflight, the freedom of fishing, or any other high seas freedom,” Groves wrote. To date, the US has four claims to mine vast areas of the deep seabed in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone beneath the Pacific Ocean, a prime area for polymetallic nodules which stretches from Hawaii to Baja.

“As far as I know, there are proponent voices from both the business and the academic circles inside the US urging their country to ratify the convention, but for the current US government, prospects look dim,” Xue Guifang said: “I believe the US, once ratifying the convention and joining the ISA will provide more opportunities for US companies.”

Louise Casson with Greenpeace International told NewsChina in an email interview that despite the US shying away from ISA negotiations, it remains active in seabed mining by cooperating with ISA contractors. “A subsidiary of the American weapons company Lockheed Martin, UK Seabed Resources Ltd, has two exploration contracts in the Pacific through the UK government,” Casson said.

Technicians on a Chinese science vessel inspect samples drilled from the ocean floor in a contracted area for polymetallic sulphides in the southwestern Indian Ocean

Uncertain Future

For now, the timeline for commercial seabed mining is unclear. On the ISA meeting sidelines, a spokeswoman for a private contractor said her company is eager for the ISA to approve the draft exploitation regulations that would allow mining of seabed resources. She also complained about the increasing environmental concerns. “We have invested hugely in exploring our contracted area, and we are still not sure if we will make a profit, particularly under the pressure of environmental NGOs,” the representative said, requesting anonymity.

Dan Porras from DeepGreen, one of the main international companies involved in seabed mining told the reporter that the biggest concern for DeepGreen at the moment is “continuing to develop both offshore and onshore technology systems for obtaining important base metals from polymetallic nodules from the Clarion Clipperton Zone,” while “progressing environmental impact assessments to be able to confidently and accurately describe the impact that we believe our operations will have on the marine environment.”

Numerous scientific studies show the devastating impact seabed mining has on marine ecology. In late July, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) added the scaly-foot snail to its Red List of Threatened Species – the first species to be threatened by deep-sea mining. The marine animal lives in just three areas in the western Indian Ocean, which include sites zoned for ISA exploration.

According to the IUCN, the effects of seabed mining on the unique ecosystems in the deep ocean are still unknown. But the scraping of the sea bed could risk wiping out whole ecosystems which contain species that are unique to that location. Pollution from noise, light, vibrations, leaks and spills, as well as sediment plumes which could affect filter feeders are all problems that need to be considered. The IUCN has called for more baseline studies and stringent environmental impact statements before licenses are granted to mine the deep ocean.

Most interviewees were pessimistic about the ISA approving the seabed mining regulations by 2020, which might be good news for environmentalists seeking to delay the impacts on the ecosystem.

“No one should take the cake until everyone is satisfied,” a delegate from a developing country told NewsChina on the ISA meeting sidelines: “There are too many opinions and efforts put towards benefit sharing.”

In Xue Guifang’s view, contractor interests and environmental concerns should weigh equally in the ISA decision-making process.

“The UN advocates a three pillar model – economic, social, and environmental – for sustainable development,” researcher Zhang Dan told NewsChina: “We should strike an ideal balance rather than emphasizing any one aspect.”

Old Version

Old Version