Master writer-director Jia Zhangke tells NewsChina about his latest gangster film, Ash Is Purest White, a decades-spanning story exploring the social and ideological changes overseen from the twists of fate of an outlaw couple

Jia Zhangke has never forgotten one particular scene from his childhood: in the late 1970s, in Fenyang, a small county in northwest Shanxi Province, dozens of boys from his primary school decided to form a sworn brotherhood. The kids stole a piece of dried turnip from the roof of a house and cut it into slices. They shared the turnip, kneeled and kowtowed to each other, and thus the brotherhood was sealed. Jia was one of these boys.

Decades later, Jia, already one of China’s most prominent movie directors, revived the scene in his latest gangster epic, Ash Is Purest White. At the beginning of the film, a group of mobsters gather in a nightclub to pledge their brotherhood as they pour bottles of liquor into a pot before drinking their share.

Released on September 21, Ash Is Purest White has become a big box-office success and is Jia’s highest-grossing film so far. The film centers on a tumultuous love story about a gangster couple that transcends 17 years. The movie also finds the director re-examining themes that he has explored over his lifetime in his films and writing: the passage of time, lost values, the predicament of modernity and the dilapidation of parts of rural China.

Code of Brotherhood

Jianghu, which literarily translates as “rivers and lakes,” refers to a network of communities that operate independently on the fringes of respectable mainstream society. Those living in the jianghu – merchants, craftsmen, beggars, vagabonds, bandits, outlaws and gangsters,

follow their own moral code, which they view as superior to laws mandated by the government. The jianghu concept has inspired countless movies and novels, particularly wuxia (martial arts) and action movies.

Yiqi, meaning the code of brotherhood or a sense of obligation in personal relationships, is the most essential value followed by adherents of jianghu. Relationships in the jianghu world often take the form of voluntary kinship, with the sworn brotherhood being the most prevalent form. Brothers are expected to put their brotherly relationships above all other commitments and create an environment of mutual support.

For more than two decades, Jia had dreamt of making a film based on these concepts. Now the dream has been fulfilled in his latest film, Ash Is Purest White, in which he explores how a group of firm believers of traditional brotherhood values have inevitably changed with the march of time.

The story, told in three parts, begins in 2001 in Datong, a crumbling coal-mining city in Shanxi Province. Bin (Liao Fan) is a small-time mobster who owns a nightclub and leads a group of men. Hong Kong action movies starring the likes of Chow Yun-fat had an influence on Bin, who expects to be treated as a godfather. His devoted girlfriend Qiao (Zhao Tao), a terrifyingly independent and empowered woman, claims that she is not part of her boyfriend’s jianghu underworld.

In the meantime, a new generation of mob factions is growing, ready to take Bin and his men down when given an opportunity. One evening a sudden ambush by a gang of young bikers catches them off-guard. When Bin is severely beaten by the violent youngsters, it is Qiao who saves his life by firing off an illegal pistol that belongs to Bin. After the couple is arrested, Qiao claims ownership of the gun, so Bin gets out of jail after a year, and she has to stay in for five.

After being released in 2006, Qiao has to cope with a totally different world. Bin never visits her in jail and has moved to a town near the Three Gorges Dam. Qiao ventures down the Yangtze River in search of Bin, expecting to resume their life. After meeting various people along the way and later being rejected by Bin, Qiao realizes that nothing stays the same and that there is no going back.

The third chapter of the story is set at New Year 2018. Qiao, who never married, finds Bin back in Datong, though he is now wheelchair-bound after a stroke. Even though she has been rejected and hurt by this man, Qiao silently takes care of the man and his wounded pride, not only out of love, but more importantly out of her loyalty to jianghu values that have vanished over the passage of time.

The film has been well-received for its feminist portrayal of the character Qiao, a woman on the fringes who has wisdom, dignity and an iron will. It is Qiao that seeks to restore the destroyed traditions and values of the jianghu world and remains the same when other characters change.

Zhao Tao, Jia’s real-life partner and his favorite actress, felt excited when she landed the role of Qiao. In order to explore the character, she read lots of reports and biographies about female criminals and women in jail. She wrote a character history herself, imagining all Qiao’s life experiences from birth to death.

Zhao initially imagined Qiao as a typical jianghu woman, strong, tough and sticking to the jianghu code, but later she rejected this assumption. “[Being a] jianghu woman is only one side of Qiao. Her behavior and actions are not merely those of a daughter of jianghu, but, more essentially, as a woman,” Zhao told NewsChina.

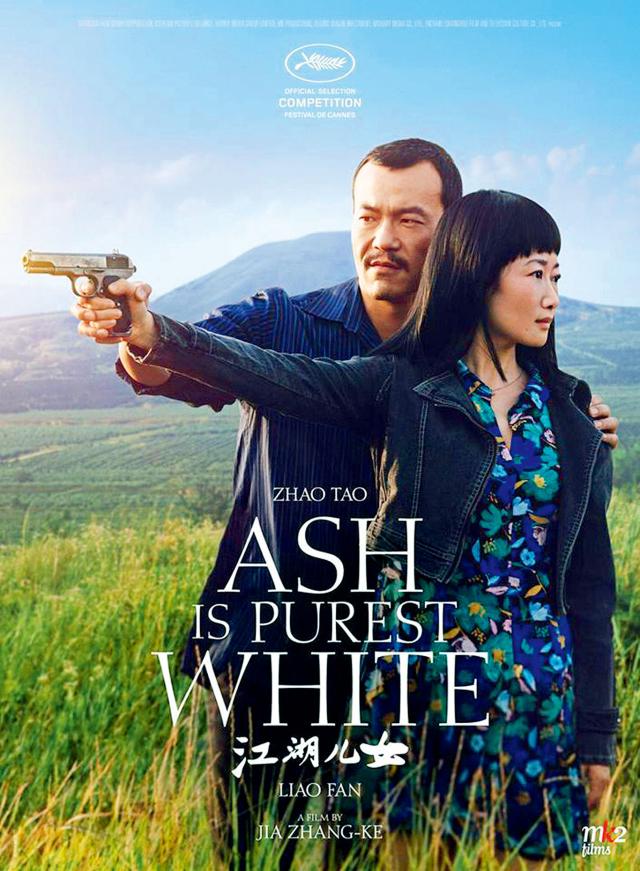

A still from Ash Is Purest White

Fading Jianghu

One significant symbolic image in Ash Is Purest White is the golden statuette of Guan Gong, a red-faced, long-bearded, sword-wielding Chinese deity based on the historical Guan Yu, a third century military commander. Guan Gong is widely revered by jianghu adherents for epitomizing righteousness and loyalty, which they seek among themselves.

“What Guan Gong symbolizes is the soul of jianghu culture,” Jia told NewsChina, “In history, Guan Gong hailed from Shanxi Province, so Guan Gong worship plays a vital part in local culture.”

As a Shanxi native himself, Jia also used to be a worshipper of jianghu and what it stood for.

In the late 70s and 80s, a time when entertainment and cultural resources were seriously lacking, Hong Kong martial arts movies almost served as a religion for teens and youths. As Jia recalled, video parlors could be found in every nook and corner of China, all playing pirated Hong Kong martial arts or gangster movies.

Jia spent much of his childhood in a dimly lit, small video parlor thick with the odor of the tobacco and sweat, watching Hong Kong martial arts and gangster films. Leaving the theater, his head was still reeling with the street fights, gun battles, fake bank notes, blood splatters and fluttering doves that were typical tropes of these pictures.

The movies roused the imagination of a fictive jianghu world. Imitating the gangsters on screen, Jia and his buddies formed their brotherhood, took part in fights, borrowing the demeanor and

jargon. Hong Kong actor Chow Yun-fat, in particular, known for portraying charismatic mafia gangsters, was the teenager’s role model.

Nevertheless, the reality was nothing like so romantic and heroic as on the screen. After years of disorder, in August 1983, the Chinese government launched a severe crackdown on crime, calling for criminals to be punished “promptly and severely.” In the months that followed, tens of thousands of mobsters were arrested. Many were executed.

Jia cannot forget the scene when he witnessed his classmates and “big brothers” being arrested, being paraded before the public with their hands tied by a thick rope. “I was so shocked, as if my head had been heavily hit by a club. It was at that moment that I realized I’d already grown up and I had to say goodbye to those messy old days,” Jia recalled.

The director has suggested that Ash Is Purest White in some way reflects his youth, with sentimentality and nostalgia for a lost jianghu world. He stressed that what he is attempting to display is the real jianghu culture and ideology rooted in people’s daily lives instead of the imagined highly romanticized jianghu underworld in a fictional wuxia setting.

“Jianghu in real life does not necessarily involve particular rules and customs as they are shown in martial arts movies or Hong Kong gangster films. For example, workers at the same factory might very naturally form an exclusive brotherhood; a small community might produce its own ‘big brother’ figure; a group of people would establish a strong connection out of a certain incident,” Jia told NewsChina.

“What was the bond that connected them? In the past, it was mainly the traditional code of brotherhood that bound them, and, of course, having common interests also played a part,” he added.

In modern China, many jianghu traditions and values have been lost. With the increasing influence of free-market policies and the impact of widespread urbanization and globalization, the brotherhood, which used to be tied with loyalty and mutual support, has been

reduced to mere money relations.

“Nowadays gangs have transformed into companies and street fights have a price list. There’s a joke in Shanxi about local mobsters – two men had a fight and each called on a group of thugs-for-hire to help them. The thugs from the opposing sides actually belonged to one rogue company. So they took the money, just pushed and shoved each other around a bit and then they went home together,” Jia told NewsChina.

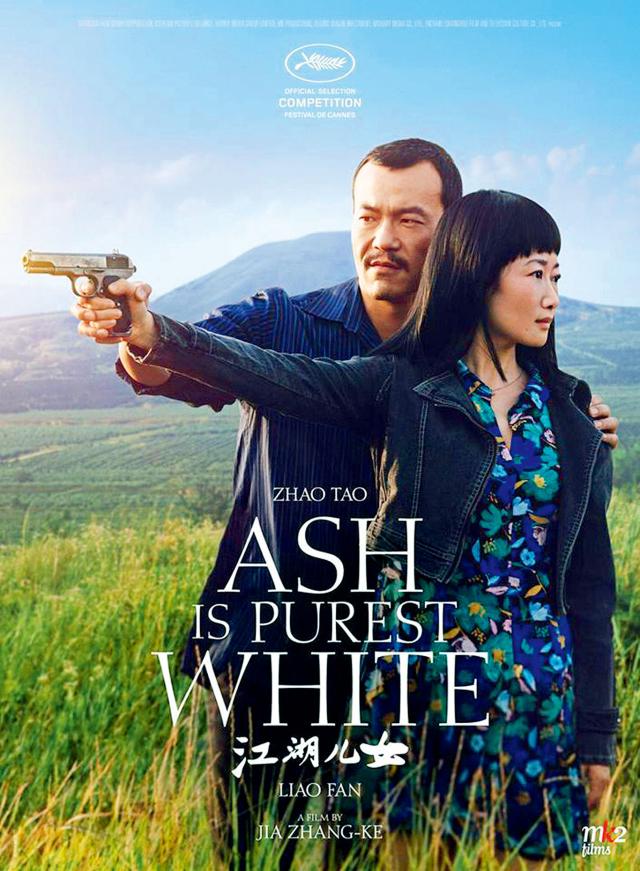

The poster for Ash is Purest White

Debate on Cinema Art

Ash Is Purest White has been well-received by moviegoers with an average rating of 7.7 out of 10 on China’s content-reviewing website Douban. It was selected to compete for the Palme d’Or at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival.

But the film was harshly lampooned on social media by Hu Xijin, outspoken editor-in-chief of State-run tabloid the Global Times, who compared it to “stinky tofu” and called it “depressing” and “full of negative energy.”

“Negative energy can attract audiences in a way like how opium gets people hooked. But I still hope filmmakers in China can learn from Hollywood and Bollywood to produce more movies with normal views about what’s good and what’s evil,” Hu wrote on China’s Twitter-like Weibo on September.

Jia responded to the harsh criticism in a lengthy Weibo post full of wit and irony, which has been shared more than 68,000 times, receiving 128,000 likes and 30,000 comments.

“I believe energy is built on the basis of telling the truth as much as possible. The truth is the most powerful source of positive energy. Turning a blind eye to what’s really going on would block access to facts and generate more negative energy,” Jia wrote.

“Your job is to report ‘a complex China’ and I am interested in telling stories about ‘complex characters.’ […] Regarding ‘normal views about what’s good and what’s evil’ – what I don’t really understand is: who should be the judge of what is normal and what is not?”

Jia’s response immediately triggered a vigorous debate online on art and truth, with most netizens applauding his frankness and joking about Hu’s narrow-mindedness. The most liked comment said “Director Jia is not fake [‘Jia’ is a homophone for ‘fake’ in Chinese], editor Hu is real nonsense [“Hu” is a homophone for ‘nonsense’]”. “Telling the truth shows the greatest empathy. Presenting a false sense of peace and prosperity is the saddest thing to do,” another user wrote on Weibo.

Jia expressed his concerns over the current “moralistic tendencies” of the contemporary cultural environment during the interview with our reporter.

“Chinese people in the 1980s had already transcended moralism with regard to literary and art criticism,” the director pointed out, stressing that audiences in the past were more open and liberal in dealing with the relationship between art and morality.

“Nowadays, audiences often adopt a moralistic perspective to evaluate a film, criticizing some for ‘delivering wrong moral values’ or mercilessly attacking some works for touching on extramarital affairs,” Jia said.

“But it is the vulnerability in human nature, the variety, subtlety and complexity of human emotions and also relationship dilemmas that art explores. That’s why we have so many literary works and films centering on LGBT [issues], extramarital affairs or even incest – those are areas of human emotion that we need to understand. It’s artistic degradation if we take the moralists’ stance and treat all these topics as taboo,” Jia told NewsChina.

Old Version

Old Version