Beijing’s first two “red alerts” for pollution highlight the city’s infamous winter smog, which is mainly

caused by indoor heating and vehicle exhaust fumes, neither of which can be mitigated in the short term

“Since November, for nearly two months this winter, we’ve had to keep the lights on at home even in the daytime because of the frequent gloomy days caused by heavy smog,” 60-year-old Beijinger Yan Li told NewsChina in late December.

The blanket of pollution that smothered the capital in late 2015 confined Yan and her two-year-old grandson to their home for much of the season.

In December, for the first time, Beijing issued “red alerts” for pollution, the highestlevel alert in a four-tier warning system. There were two: the first spanned from December 8-12, and the second from December 19-22. The city’s concentrations of PM2.5 – those fine particles less than 2.5 micrometers (0.0025mm) in diameter that can penetrate deep into the lungs – rocketed above international standards. Concentrations of PM2.5 greater than 250.5 micrograms per cubic meter are considered “hazardous” by the US Environmental Protection Agency, which sets the highest acceptable average concentration over a 24-hour period at 35.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) standard of 25 micrograms is even more strict. At its worst in late 2015, Beijing’s concentrations exceeded 500 micrograms per cubic meter in most parts of the city and its surrounding regions, 20 times the WHO’s highest acceptable amount.

The red alerts triggered a series of actions across the capital. Schools closed down, vehicles were pulled off the roads, and construction projects and factory production slowed under temporary limitations. The two alerts were perceived by the general public as a sign of the government’s willingness to take real action to curb pollution in response to increasing discontent from the people regarding the country’s environmental problems.

Action and Inaction

According to definitions from the China Meteorological Administration, there was an annual average of five “smoggy days” during the 1960s, while that number climbed to 26 in 2013. Visibility also dropped from an average of 26 kilometers in the 1960s to 22 kilometers in the 2010s.

The government has been fighting worsening air pollution with a new series of environmental policies. The National Action Plan on Air Pollution Control issued in 2013 set objectives for areas of Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei Province (a region abbreviated to BTH) to reduce concentrations of PM2.5 by 25 percent by 2017, based on their 2012 levels. Beijing specifically would need to keep its average concentration of PM2.5 within 60 micrograms per cubic meter. To accomplish these goals, Beijing issued the Clean Air Action Plan 2013-2017 and announced it would invest 760 billion yuan (US$117bn) in air pollution controls by 2017.

In mid-2013, Beijing instituted an emergency response program for air pollution that included a four-tier alert system used for “heavy pollution” days, made up of blue, yellow, orange and red alert levels. Red alert, the most serious, is supposed to be announced at least 24 hours before experts predict the city will be shrouded in hazardous-level concentrations of air pollution for three or more consecutive days.

Yet, until last December, the local government failed to announce a single red alert since the program’s launch in 2013, despite the city’s frequent strings of hazardous air quality days. The silence was allegedly to avoid the economic and societal costs.

According to Wang Bin, head of the emergency response department of the Beijing Municipal Environmental Protection Bureau, Beijing issued red alerts in December because of upgraded standards that imposed stricter regulations for air quality. “It does not necessarily mean air conditions are worse than in the past,” Wang added.

When the Beijing emergency response program underwent revisions in March 2015, the conditions required for a red alert changed from three consecutive days of “hazardous” air pollution (where the Air Quality Index [AQI] is 301 or more) to the present three consecutive days of “very unhealthy” air pollution, classified as AQI levels of 201 or higher.

Over the past few years, China has started to show more transparency regarding its air quality, and the red alerts have been hailed as further evidence of this new openness.

The reasons Beijing tightened its red alert standards in early 2015 are threefold, according to Zou Ji, vice director of the National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation. The first is the city’s geography – the mountains along its northern and western borders trap pollution; the second is Beijing’s important role as the country’s capital, which requires stricter environmental standards to maintain the country’s international image; and the third is the city’s massive population of over 25 million, which elevates the need for tougher regulations.

“The purpose of the red alerts is emissions reduction,” Zou told State-funded media site The Paper during a recent interview.

He added that, considering the harsh reality that eliminating pollution cannot be realized in China in the short term, stiffening red alert standards could be a temporarily effective measure in treating some symptoms of the chronic affliction that has haunted China for decades.

Indeed, in 1999, Xie Zhenhua, then the director of what is now called the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP), stated publicly that “air pollution will not be the country’s legacy in the new century.” However, the nation’s substandard air quality continues to draw headlines from around the world. At the same time, the government invested a lot into improving its air qualitymonitoring technology in recent years, allowing measurements of pollution to become significantly more precise and timely than in the past.

During the red alerts in December, more than 2,000 factories and 3,500 construction sites in and around Beijing were ordered to either reduce production or close entirely.

Half of the city’s vehicles were kept off the road through restrictions based on whether their license plates ended in an odd or even number. Beijing authorities dispatched a large number of extra police officers to ensure drivers were following the rules.

Cheng Shuiyuan, a professor of environmental science at Beijing University of Technology, evaluated the effectiveness of the red alerts. He concluded that they helped reduce PM2.5 density by 20 to 25 percent, and cut airborne pollutants by an average of about 30 percent.

Sources

According to the China Meteorological Administration, from December 19 to 22, heavy smog blanketed a large swath of northern China, stretching from the mid-western city of Xi’an, through Beijing and up to Shenyang in the country’s freezing northeast.

At a December 22 press conference, MEP spokesman Tao Detian said that the total affected area was as expansive as 660,000 square kilometers, with 470,000 square kilometers suffering “heavy pollution.” Along with Beijing, another 10 cities in neighboring areas issued red alerts.

After years of monitoring air quality and analyzing data, Chinese researchers concluded that the five major sources of PM2.5 in Beijing are vehicle emissions, coal burning, industrial production, dust and pollution produced in neighboring regions.

Local emissions make up over 50 percent of Beijing’s PM2.5 problem, according to a December article in the journal Atmospheric Environment. In 2013, the industrial sector (44 percent) and residential sector (27 percent) were the dominant contributors to urban PM2.5 in BTH. During the winter, the residential sector surpasses the industrial sector to become the largest contributor to air pollution. According to the article, residential sources, such as coal-burning stoves and furnaces, may even make up as much as 48 percent of contributions in January, while they only account for some 10 percent of total emissions at other times of year.

A Peking University paper published in October in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences drew a similar conclusion.

From the research team’s analysis of pollution data collected from 2010 to 2015, “the heating has contributed a more than 50 percent increase (on average) in PM2.5 in the winter months in Beijing since 2010. This means that one-third of the PM2.5 [during these] months is due to heating.”

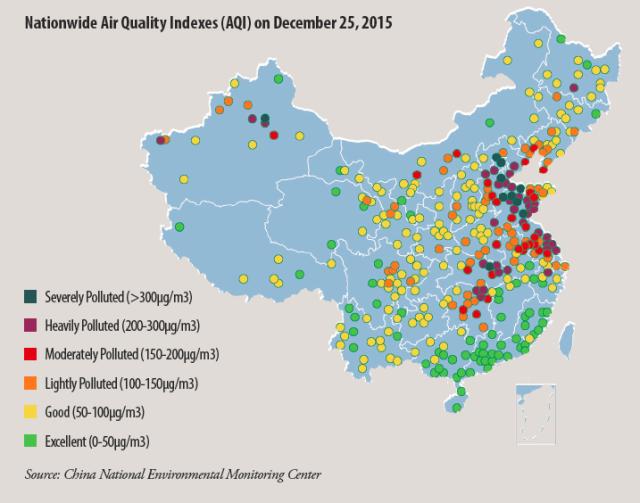

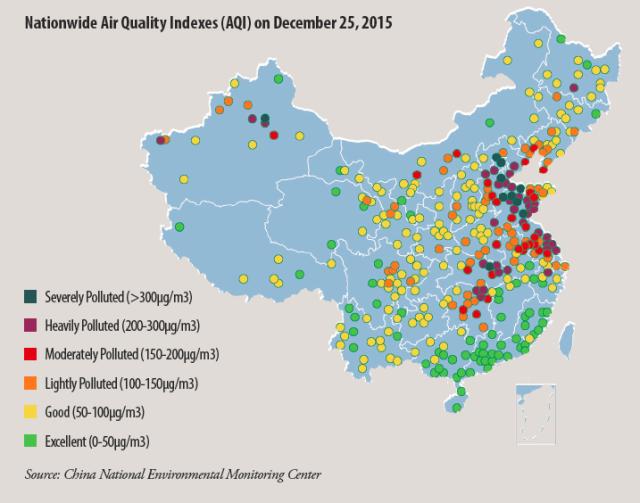

Nationwide Air Quality Indexes (AQI) on December 25, 2015

Meng Fan, an air pollution researcher at the Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences, agrees that coal burning from private households is a major contributor to the region’s recent air pollution, adding that it introduces a significant amount of carbon monoxide into the air. The fact that Beijing itself is like an island of heat trapped by mountains to the north and west worsens the situation. Without strong winds blowing in from the northwest to blast the bad air out of the city, the capital’s air just keeps circulating in a closed system. At present, there is no scientific model available that can precisely imitate the complex patterns of air circulation within Beijing’s borders.

According to Peng Yingdeng, a researcher at the National Engineering Research Center for Urban Pollution Control, Beijing’s general air quality in November and December was not any worse than usual. “Yet due to this year’s severe weather conditions caused by El Niño, which reduced the [amount of] cold air, the resulting stable atmosphere made Beijing prone to spells of low air pressure that trapped air pollutants closer to the ground,” Peng told NewsChina.

Although the largest source of winter smog has been identified, it is hard to implement regulations that successfully restrict coal burning in China’s sprawling cities. Beijing’s municipal government started to install new natural-gas heating facilities in 2011 to phase out coal-based heating sources in the city center.

However, outside the downtown region, most furnaces in Beijing are still coal-burning and have yet to be renovated. A recent inspection of a few districts in the BTH region organized by the MEP found substandard coal quality remains a key problem in many places.

Among 10 major winter heating providers, the coal used by seven of them fell short of the required standards.

According to a statistical analysis released in late 2015 by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, coal production and coal imports in China peaked in 2013, and both declined at an accelerating rate throughout 2014 and 2015. Chinese coal consumption was down 5.7 percent year-on-year for the first nine months of 2015. Yet despite the positive trends of surging renewable energy and slower growth in the demand for power, the latest MEP statistics indicate coal still dominates as the biggest energy source for much of northern China, accounting for as much as 90 percent of total energy consumption. Even more paradoxically, a Greenpeace analysis released in November found that, despite falling coal demand and major overcapacity in coal-fired power generation, China issued environmental approvals to 155 coal-fired power plants from January to September 2015, averaging out to about four plants per week. In total, these plants have a capacity of 123 gigawatts, more than twice the size of Germany’s entire coal power output. This apparent coal bubble represents a widespread, outdated mentality towards conventional energy, in spite of its damaging effects on the environment and human health.

Every year, outdoor air pollution is a contributing factor in the deaths of an estimated 1.6 million people in China, according to a scientific paper released by Berkeley Earth in August. That comes out to about 4,400 people a day.

China has begun to take big steps to tackle air pollution caused by power plants and other industrial contributors in the past decade, shutting down some of the least efficient fossil fuel-burning power plants and committing trillions of US dollars to clean energy. In fact, the average PM2.5 concentration in Beijing from January to October 2015 was 69.7 micrograms per cubic meter, an impressive 21.8 percent lower than the previous year.

Winter smog in November and December, however, failed to sustain this achievement.

The Beijing Municipal Environmental Protection Bureau announced in early January that the city’s PM2.5 density decreased by just 6.2 percent in 2015 compared to 2014 figures, although that still exceeded the goal of a 5 percent reduction set at the beginning of 2015. The annual average PM2.5 concentration in 2015 was 80.6 micrograms per cubic meter, compared to 2014’s 85.9 and 2013’s 89.5.

A source working in the environmental sector who spoke on condition of anonymity told NewsChina that emissions cut during the red alert periods from vehicle exhaust, factory production and construction projects have been nearly maxed out, so there is little else that can be done to further lower emissions during future pollution emergency periods.

From a long-term perspective, the restructuring of the energy and industrial sectors is still essential to successfully tackle air pollution, said Chai Fahe, vice president of the Chinese Research Academy of Environmental Sciences, at an MEP conference in early December. At the same time, to mitigate the intensity of each wave of pollution, local governments should aim to forecast them early and initiate quick countermeasures, which are equally important in solving the problem.

Old Version

Old Version