Prominent visual artist Xu Bing’s first feature film is composed solely of footage from China’s millions of surveillance cameras, altering viewers’ concepts of reality and showing them just how often they are being watched

A dragonfly’s eyes are huge compared to the rest of its body.

They are an example of compound eyes, meaning they are made up of many tiny lens units known as ommatidia. Some subterranean insects only have 20 ommatidia and a typical housefly has upwards of 3,400, but dragonflies have about 30,000. Their eyes’ large, globular shape also gives them a 360-degree field of vision.

Xu Bing, a renowned Chinese contemporary artist who has won a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” and held solo exhibitions in five continents, named his debut film after these all-seeing organs.

Dragonfly Eyes takes an unprecedented form for a feature-length production.

Eschewing camera operators and on-screen actors, Xu’s film is a compilation of surveillance footage collected from thousands of security cameras and presented in narrative form. Through this project, which is set to be complete within the year, Xu aims to reveal a truth about modern life which people are generally blind to — even during some of your most intimate moments, you are being watched.

Unprecedented “Do you know how many surveillance cameras you passed on your way here?” Xu asked our reporter with a grin.

In 2014, the Wall Street Journal quoted a security industry specialist who estimated that China is home to 100 million such cameras, or about one for every 14 people. And they catch it all. As if to illustrate this exact point, rough cuts of car crashes, gang fights, a suicide, murders and even a lightning strike are stuffed into the movie’s threeminute trailer, which was released on December 31, 2015. Unlike other films, which would use special effects for these scenes to imitate reality, Xu’s film presents the reality itself. Every single frame, every shot – be it comical or horrifying – is not a reenactment; it actually happened in someone’s life.

“Dragonfly Eyes does not belong in any genre,” Xu told our reporter.

“We might call it a ‘film of samples.’” As all of the film’s scenes were sourced from surveillance footage, it was impossible to have a main character consistently appear throughout the movie. To fix this problem, Xu made the protagonist a woman who frequently undergoes cosmetic surgery and therefore constantly changes in appearance. Her name is Dragonfly. To create the audio for Dragonfly’s journey, Xu had voice actors dub the video clips, as security cameras often don’t record sound.

Xu embarked on this project four years ago. The greatest challenge he faced, in its early phase, was access to the materials. Obtaining surveillance footage at the time was immensely difficult; Xu tried many different tactics, even resorting to persuading security guards or friends who work for TV stations to acquire film for him. Yet, struggling with the potential legal complications and his own inability to get his hands on enough tape, Xu suspended the project.

The turning point occurred in 2015, when Xu started noticing that more and more security camera footage was being aired publicly on law-related TV shows and online platforms. Xu also found many live-streaming websites that were filled with footage from surveillance cameras monitoring apartment complexes, bars, highways, hospitals

and more. The discovery facilitated the process of collecting film tremendously. Late last year, Xu and his 12-member team collected about 10,000 hours of footage by keeping 20 computers running 24 hours a day.

This sudden abundance of material gave Xu more creative leeway to flesh out his original storyline. “I had a simple outline for the story in the very beginning, but as the number of video sources increased, my script kept changing right along with it,” he told NewsChina. “Those materials were a real-time record of people’s everyday lives, there was no way to predict what would happen next; all we could do was interact with it.” In Xu’s view, the collected footage “possesses a vitality” that allows it to constantly grow and transform. “In other words, throughout the process of gathering and editing the materials, I was not sure what the work would eventually turn out to be.” But apart from the quotidian scenes of ordinary life, what really shocked Xu about the footage was that it was riddled with gore and violence. Car accidents, fistfights, robberies and murders had all been captured by the all-seeing lenses. “The level of cruelty was too severe to be used in our film,” Xu told NewsChina.

True or False?

Xu was born in the central Chinese city of Chongqing in 1955.

He grew up in Beijing, where his father was the head of the history department at Peking University. Xu was relocated to the countryside from 1975 to 1977 as part of Mao Zedong’s movement to send urban youths to work in rural areas for “re-education.” In 1977, Xu started studying at Beijing’s Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA).

After graduation, he did a stint of teaching before receiving his Master of Fine Arts there in 1987.

At the invitation of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Xu moved to the US in 1990 and remained there for 18 years. He received a MacArthur Fellowship in 1999, presented to him for his “originality, creativity, self-direction and capacity to contribute importantly to society, particularly in printmaking and calligraphy.” In 2008, he was appointed CAFA’s vice president and thus returned to Beijing. After a six-year term, he gave up his vice presidency, and now advises the academy’s doctoral students as a professor. He also serves as a professor-at-large at Cornell University.

Xu is known as a bold artist who questions the status quo and rattles existing cultural assumptions and world-views. Many of his most thought-provoking pieces contemplate the relationships between language and meaning, reality and unreality, East and West, as well as tradition and modernity.

In his monumental project Book from the Sky (1987-1991), the artist invented 4,000 “new” Chinese characters, which looked similar to standard Chinese script but were in fact completely fabricated. Xu carved the characters by hand into wooden printing blocks, then used them as movable type to print ancient-looking volumes and scrolls, which he displayed both laid out on the floor and suspended from the ceiling. The work completely deconstructed the relationship between language and meaning, something that “infuriated” many intellectuals when it was first exhibited in Beijing in 1988 because they “were so accustomed to seeking out meaning in words,” he recalled.

In contrast to Book from the Sky, which no one can decipher, Xu’s Book from the Ground (2007) is a piece made for everyone to understand.

In the latter, Xu bypassed the need for language and used icons and emojis to tell the story of 24 hours in the life of a typical white-collar urbanite. The emoticons form lines on the page, just like printed type. Regardless of their linguistic or cultural background, viewers can easily comprehend this pictorial storytelling style through images that transcend verbal language.

The postmodern, deconstructive characteristics of Book from the Sky and Book from the Ground are also clearly embodied in Dragonfly Eyes. In the film, the artist often playfully but thoughtfully challenges the audience’s conceptions of reality, rationality and the notion that, in this day and age, we are constantly under surveillance.

A sense of satire permeates the entire avant-garde film. The first shot of the trailer is of a projector screen that’s playing what starts off every major Chinese film – the logo of China’s State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television (SAPPRFT), a golden dragon on a green backdrop that is as familiar to Chinese moviegoers as MGM’s roaring lion is for Western viewers. This footage, like the rest of the film, was originally recorded by a surveillance camera.

But the dragon is not a studio’s production logo, like MGM’s lion. Instead, it represents a stamp of SAPPRFT approval, signifying that the film it precedes has been licensed for screening in Chinese theaters. The effect is pure irony, Xu told The Art Newspaper China: “[Dragonfly Eyes] would never get a ‘dragon license’… so putting a ‘faked’ [SAPPRFT] logo at the beginning of our movie creates a sense of absurdity and enhances the degree of satire.” The entire plot itself also plays with the line separating truth and fiction. Xu said the basic plot line originated from a news story that went viral a few years back, in which an initially unattractive woman had so much cosmetic surgery before meeting her husband-to-be that, after they married and she gave birth to three homely children, her husband sued her for deception.

It later came to light that the story had been fake. But as Xu used actual surveillance footage to tell this tale, he made it “real,” allowing viewers to watch it unfold.

Apart from documentaries and biopics, most films are viewed as works of fiction, so Xu’s unique, “sampling” form of filmmaking challenges people’s definition of truth. As he concluded after watching thousands of hours of tape: “Real life is far more absurd and illogical than any work of art or anything we could ever imagine.” ‘Reality’ Show Xu said both George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and the 1998 American movie The Truman Show provided nuggets of inspiration for Dragonfly Eyes.

“In Nineteen Eighty-Four, people still view surveillance with a sense of fear,” Xu said. “But in real life, today, the relationship between ourselves and surveillance has already changed – people are no longer afraid of it; instead they’ve learned to make peace with it, or even use it to their advantage.” The Truman Show, in which the title character learns mid-movie that his entire life is actually a reality TV show being broadcast worldwide, shows just how far surveillance can go. In Xu’s view, the future that The Truman Show prophesied has already come true. “The Truman Show conceived of a possibility, and [Dragonfly Eyes] proves its realization,” Xu told NewsChina. “Human beings have already turned the entire world into a boundless theater, and every one of us seems to have become a Truman�� performing on a stage.

The existence of today’s near-omniscient mass surveillance systems, in Xu’s view, provides humans with a new lens through which to understand truth. Throughout the course of human history, people have claimed to witness many bizarre or incredible things, but can do nothing to prove their verity. Xu believes that the security camera network gives humans a chance to record and later view history in its entirety, creating a more accurate version of oral and written historical records.

“In the film, there is a scene in which a passerby is knocked down by a loaded truck and dragged under it,” Xu told The Art Newspaper China, as an example. “We would think that man is definitely done for. But after the truck rolls over him, he gets up and… walks away.

If this scene were in a [typical] movie, it would strike audiences as unrealistic.” The fact that cameras have captured such implausible moments, therefore proving their authenticity beyond a shadow of a doubt, “forces people to reconsider the boundaries of logic and reason,” he added.

“Do you know how many surveillance cameras you passed on your way here?” Xu asked our reporter again, at the end of the interview.

“You leave your house, take a taxi, buy a bottle of water from a convenience store and make a phone call along the way – cameras might be recording your every move, it’s just that you don’t know it.”

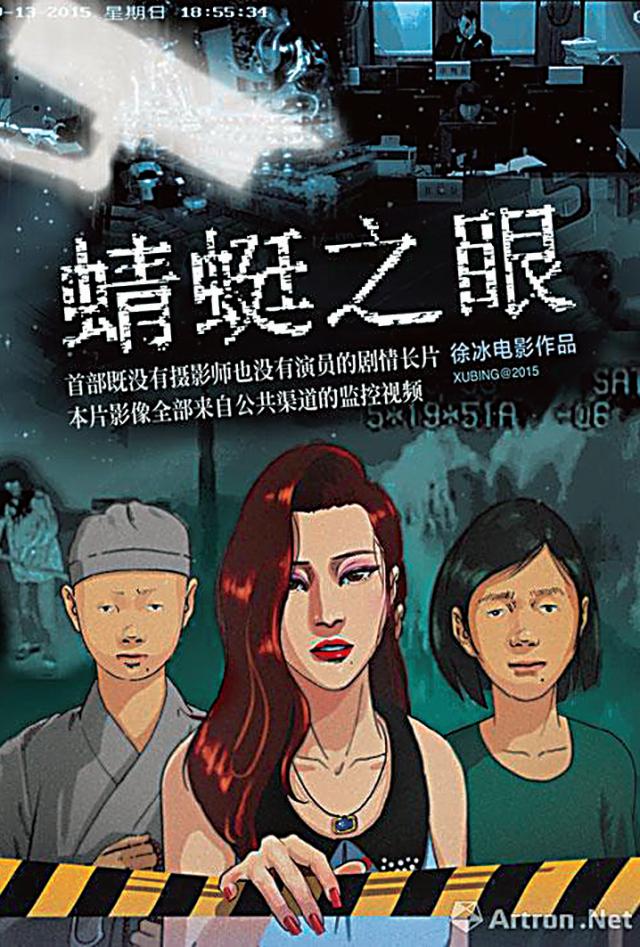

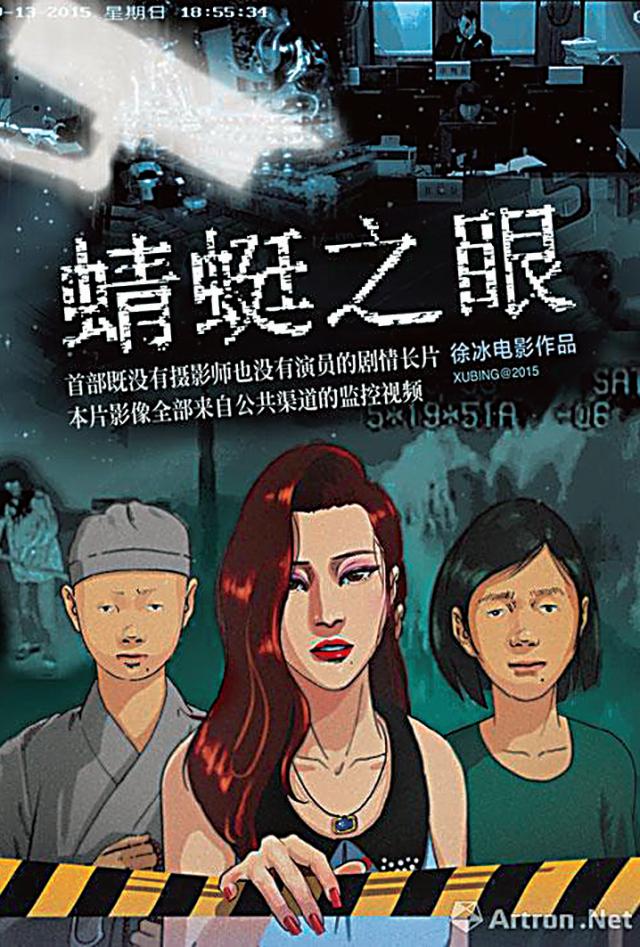

Poster for Dragonfly Eyes

Old Version

Old Version