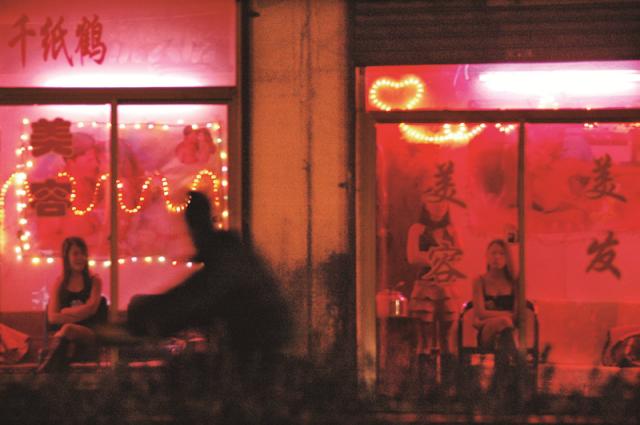

rostitution, the oldest profession in the world as the saying goes, went into retreat on the Chinese mainland shortly after the Communists took power 1949. Over the past 20 years, however, China’s underground sex industry has begun to revive despite the authorities’ continuous campaigns to “sweep away yellow” (“yellow” in Chinese refers to all things blue) particularly in its affluent coastal areas.

Prostitution in China enjoys a unique existence as it is both illegal and remarkably ubiquitous due to the country’s relaxed social control, growing wealth and the massive influx of migrant workers to cities, many of them young girls. The lives of sex workers in contemporary Chinese society are virtually unknown to the outside world.

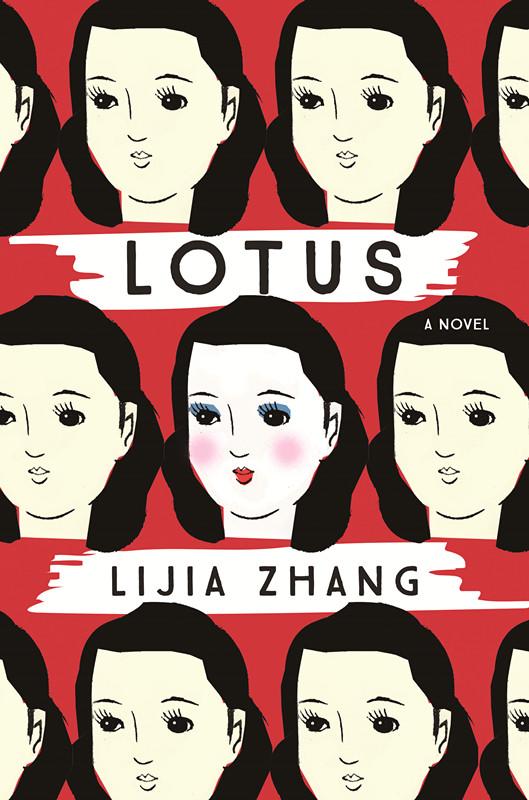

As a factory-worker-turned-writer, Zhang Lijia’s debut novel Lotus portrays at the spit-and-sawdust level the lives of “working girls,” millions of whom are estimated to have joined the trade either reluctantly or readily since China’s society has opened up. The novel was inspired by the deathbed confession of the author’s grandmother who revealed that she had been sold into a brothel in her youth.

Lotus, the novel’s 20-something eponymous main character, seeking better job prospects, makes her way from an impoverished village in the hinterland province of Sichuan to Shenzhen, a coastal mega city that forms the border with Hong Kong and is known as China’s City of Sins. Tempted by seeing the palm trees, buildings clad in shining mirrors soaring into the sky, colorful neon signs dazzling to the eye, and large ships docking on blue water in a busy harbor on a neighbor’s television set, she ventures to the city like “a newborn calf that isn’t afraid of tigers” and lands her first job at a factory with her cousin.

After a fire, however, her cousin dies. Frustrated and not having enough money left over to send any home, Lotus eventually ends up working at a massage parlor and selling her body to support herself and her brother who is studying hard in the hope of getting into college. As is the case with many prostitutes who work at the lower end of the trade, earning enough to be able to send money home is a key reason for entering the trade, and issues of filial piety are found throughout the novel, such as Lotus being greatly relieved to be able to wire money back to her hometown, pretending to have earned it through more decent work.

Another character in the novel, Bing, is a middle-aged divorced photojournalist who films sex workers, mainly Lotus and her friends, before pocketing a national photo prize. The character is based on a real photographer who spent a long time documenting the lives of prostitutes in Hainan. Through his contact with Lotus, Bing begins to take a fancy to this charming, modest but ambitious girl.

The male protagonist swings chaotically between his work and love at a time when cohabitation with a prostitute would mean the end of his official career. On the other hand, Lotus is also torn between the sins of the profession and the lure of money. Lotus, a strong believer in Buddha, eventually leaves Bing to pursue her new fate as a rural teacher. According to the author, she didn’t want a cliched ending of a “hero rescuing a fallen girl.”

Lotus, purely fictional, is a rounded and believable character thanks to the author’s contact with working girls, particularly after her acquaintance with a prostitute-turned-NGO-founder dedicated to helping female sex workers. It took 12 years, on and off, for Zhang to complete the novel after interviewing more than 100 sex workers in cities across the country including Shenzhen, Dongguan, Beijing and Tianjin.

As a former factory worker herself, the author is deeply concerned with the country’s social issues including migration, income gap, corruption and gender inequality that were flung to the fore with the country’s economic growth, which the author said have contributed to increasing prostitution. In a sense it is the author’s personal voice as a long-time champion of women’s rights coming through when Bing states “prostitution is a window through which to see the changes in China.”

Set over a period spanning from the 1980s to the new millennium, the novel gives a detailed and vivid account of a range of social problems in contemporary China including the lack of proper education for the offspring of migrant workers, collusion between corrupt government officials and businessmen, how sex workers are hired to lubricate commercial negotiations, as well as the continuous harassment and unchecked despotism of police officers when dealing with prostitutes.

In an interview with NewsChina, Zhang discussed the creation of the novel, social and economic factors that contributed to the booming sex industry in China, and debated the legitimacy of prostitution.

Old Version

Old Version