The world we knew has disappeared alongside the old year of 2016, and we have not unravelled the mysteries it has left behind to inform the way ahead. Some economists even described the eventful year as a “Black Swan Lake” thanks to so many Black Swans – a black swan being an unexpected or unanticipated event. But a beautiful swan princess may turn out to be an evil witch. Whether the future looks dark or not may depend on your perspective.

In 2016, China boasted a mix of one of the world’s highest growth rates and moderate inflation. By contrast, developed economies were struggling with slow growth, while other emerging economies were struggling with either high inflation or stagflation.

However, analysts are divided on whether this means the end of the downward cycle that started in 2012. Behind the divergence lie concerns over cost and sustainability due to the way that this perfect growth and inflation match has been achieved. And old risks are still piling up. Reality does not match fairy tales. Swans may be black or white, but reality often comes in shades of gray.

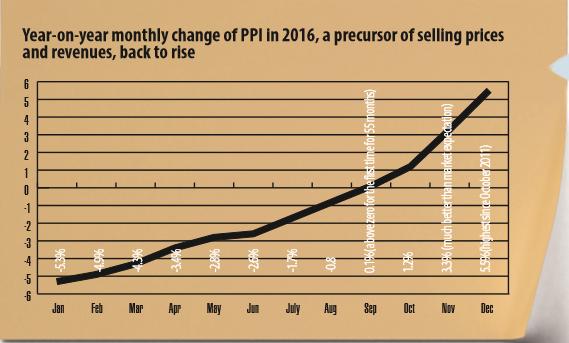

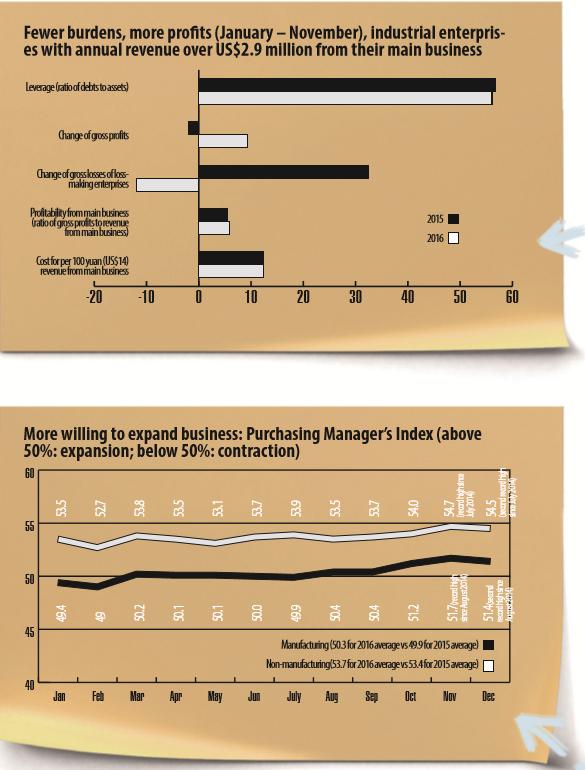

Several indicators were regarded as evidence of an improvement in China’s economic performance in 2016, particularly in the second half of the year. The producer price index, a precursor of profitability, was down by 1.4 percent year-on-year, much better than the 5.2 percent decline in 2015. The November and December figures were much higher than had been expected by the market. As a result, middle and large industrial enterprises enjoyed rising profits and falling leverage ratios and costs compared with 2015.

Signs of stronger growth are also reflected on production lines. Power consumption over the first 11 months of the year rose faster in the first months of the year over the same period of 2015. In the manufacturing sector in particular, power consumption rose after a decline in the same period of 2015. Manufacturers showed more readiness to expand their business, with the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), an indicator of business expansion, standing above the watershed of 50 percent in nine months of the year, – something it only managed for five months in 2015.

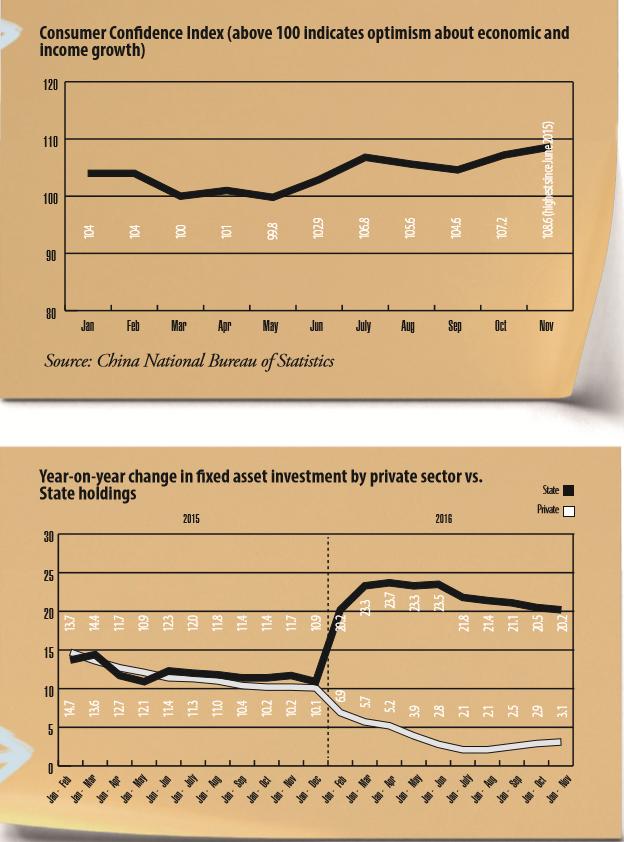

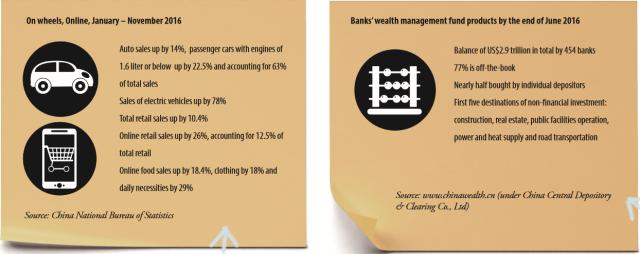

Consumers felt like shopping more. Their position as the most stable pillar of China’s economy during the post-2012 slowdown has remained unchallenged. 71 percent of China’s GDP for the first three quarters of the year came from consumption.

In May, an “authoritative figure” anonymously declared via the Party’s mouthpiece People’s Daily that China’s growth trajectory would have an “L” shape – decline, before a plateau. All the encouraging indicators seemed to have given most officials and analysts enough reason to believe that China’s economy has stabilized along the horizontal line.

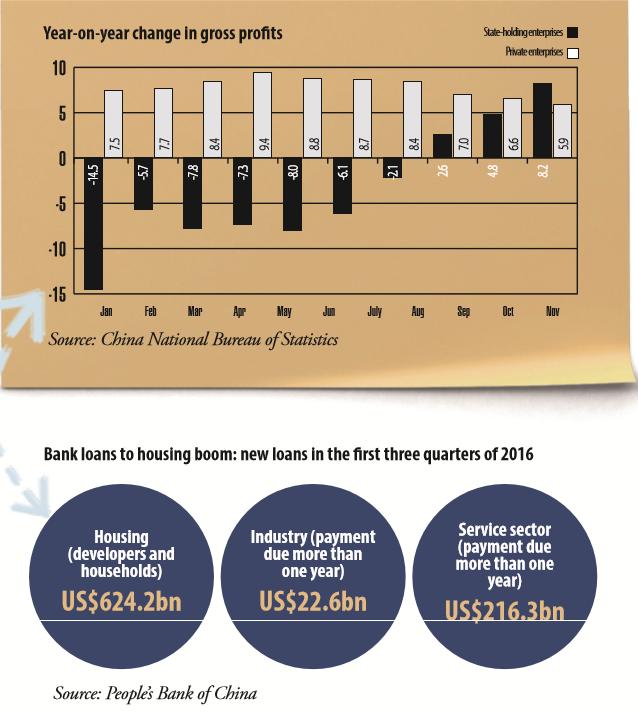

Yet analysts have also perceived some alarming factors lurking in the background. Since June 2015, fixed asset investment with State-owned holdings has kept outpacing private investment. Although investment by private investors began to move up again by September 2016, the gap between the growth in private investment and the growth in State-sponsored investment had hardly narrowed by November. One-fifth of the fixed asset investment has been spent on infrastructure construction, and budget spending on fixed asset investment increased much faster than any other source of funding. Meanwhile, in the second half of 2016, the growth of the gross profits of private companies lagged behind that of State-owned enterprises for

the first time since the massive stimulus plan was implemented in 2009 and 2010. The leverage ratio was largely brought down by private companies, while SOEs continued building up their debts. This can probably be explained by the reluctance of private investors to invest more in production.

The second large contributor was the real estate market frenzy that swept scores of major cities in 2016. Restrictions on buying apartments were relaxed at the end of 2015 to boost sales in smaller cities. However, the result was a housing spending spree in large-and mediumsized cities. The soaring revenues on the housing market attracted more investment in housing development.

The budget funding and housing fever also boosted consumption and profits. In 2016, buyers of vehicles with an engine size below 1.6 liters enjoyed a 50 percent cut of the auto purchase tax. The fiscal stimulus and economic growth, driven partly by the housing boom, brought a “happy surprise” to auto makers in China, said Xu Haidong, assistant to the secretary general of the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM), at a recent Changsha meeting of his organization. Auto sales for the first 11 months of 2016 had already exceeded the total in 2015. Although electric vehicles accounted for less than 2 percent of China’s auto sales, they recorded a staggering 60 percent year-on-year rise for the first 11 months, and are regarded as a new cash cow by Chinese auto makers. The progress was largely underwritten by fiscal subsidies.

Jiang Yuan, vice director of the industrial statistics office of the National Bureau of Statistics, noted at the meeting that the auto industry had become the most profitable part of the manufacturing sector by 2015, and the third largest industry by output. Mao Shengyong, spokesperson of the National Bureau of Statistics, cited the strong auto sales as one of the two main factors driving the highest consumption figure of 2016, for the month of November. The other was the annual Singles’ Day online shopping gala the same month.

The fiscal and housing-driven growth are not seen as sustainable or healthy. Weak private investment has particularly aroused concern from both policy makers and the public. Neither taxpayers nor apartment buyers have endlessly deep pockets. The housing fever has already cooled down since restrictions were imposed in the last two months of 2016 on buyers by the government alarmed by the frenzy. Auto purchase tax cuts will be reduced in 2017, and subsidies for electric cars will be more stringent to avoid the scams that happened in 2016. The Ministry of Commerce and the CAAM have no expectation of a repeat of the auto market boom in 2017.

The avoidance of systematic financial risks would be “put on a higher agenda” in 2017, according to the decision of the CPC Central Committee in December 2016. The decision does not specify the risks. Analysts have noticed thrilling – and perhaps worrying – stories in almost every part of the financial sector in 2016.

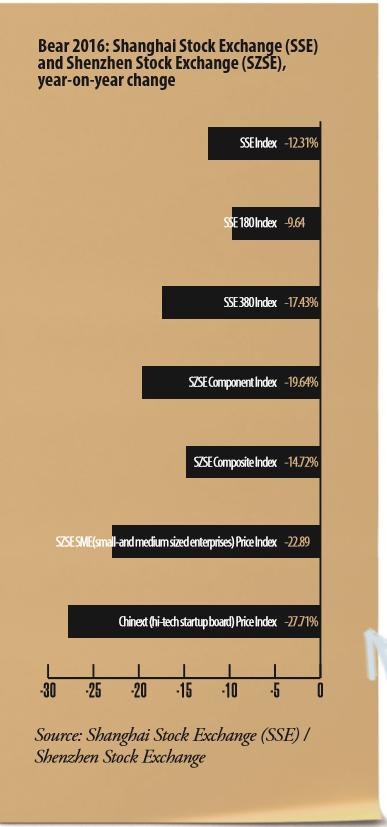

The stock market started the year with a new tool called the circuit breaker. The concept, borrowed from the US, is to avoid market stampedes by suspending or closing stock trading in the case of a price crash. However, the tool lasted only four days after frequent stampedes triggered suspension and closure several times. The market remained lukewarm for the rest of the year.

The real figures for bad loans by Chinese commercial banks remain only a legend, but they are widely estimated to be much higher than the healthy figure of “below two percent” announced by banks. More worrying is the growing shadow banking system, with its opaque operations and strongly contagious effects. Commercial banks have sold massive off-balance sheet “wealth management” products to depositors and institutional investors, and then invested the money into bonds or other debt products. As the People’s Bank of China explained in a recent statement, this creates two different types of risks. Firstly, those bonds or other debt products are also bank lending in nature. However, they are under much weaker risk control than banks’ onbalance sheet lending. Secondly, banks have been sticking to giving depositors the returns advertised, even if the investments fail, as part of the fierce competition to attract deposits. Sometimes banks used their on-balance sheet deposits to cover the losses, making the firewall between the on-book and off-book business ineffective and effectively creating potential Ponzi schemes.

A high leverage ratio is not only a lingering problem in the real economy, but an increasingly serious issue in China’s financial sector over the past two years. Banks have played a role. Institutional and individual investors in stock, bond and real estate markets got access to huge capital through complicated deals among financial institutions, including banks. The prices on those markets soared. Once the central bank or regulators in those areas began to play tough, a precipitative drop in prices swept the market. This bubble-bust cycle is a familiar pattern everywhere, and was exactly what happened in China in 2015 and 2016.

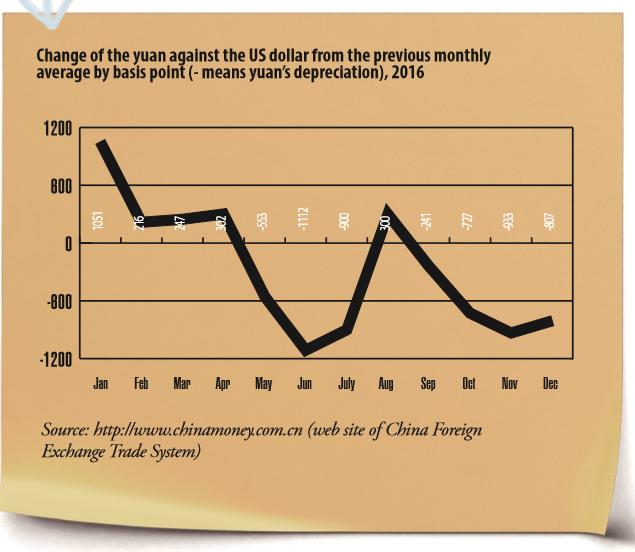

In October, China’s yuan joined the Special Drawing Rights basket, an international reserve asset created by the International Monetary Fund. It was a milestone for the yuan to become an international currency. However, the process was overshadowed by the drastic depreciation and persistent expectation for further depreciation of the currency, right after the IMF inclusion. On January 7, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange confirmed that defending the yuan’s value was the biggest reason for the US$320 billion drain of China’s official foreign exchange reserves. This again triggered debates over choosing between the exchange reserves or the exchange rate.

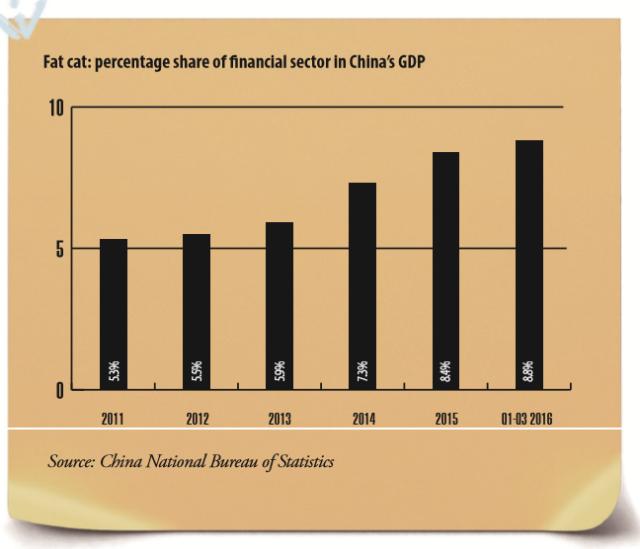

But the biggest risk of the financial sector for China’s economy is not bubbles or irregularities in any of these particular sub-markets. The biggest risk is simply that the financial sector has become too big. As Fan Jianping, chief economist of China’s State Information Center said at a forum on January 7, 2017, the value added by the financial sector accounted for a higher share of China’s GDP than in the US and the UK in 2013, and reached 9 percent in 2016, a phenomena that “has never been seen in any country in history.” He described the sector as “puffy, not well-developed.” Warnings that the sector has become an exclusive club for financial players have been resonating among analysts in their year-end reviews. It is too early for China, they stressed, to begin de-industrialization, let alone financialization.

“Seeking progress while maintaining stability” has been officially set as the main tone of China’s economy in 2017. Implementing market-oriented reform more effectively has been confirmed as the road to boosting encouraging indicators and curb tricky ones. In this regard, there are also lessons to learn from 2016. Like growth itself, the pace and way of getting things done on reform matter, not just the figures.

Old Version

Old Version