Although Feng Xiaogang has a knack for making other people laugh, he doesn’t like to laugh himself. When the 58-year-old filmmaker is spotted in public, he usually wears a very serious expression and a baseball cap that conceals half of his face under the shadow of its brim.

Dubbed “China’s Spielberg” by both domestic and international media, Feng is perhaps China’s most successful and beloved commercial filmmaker. On top of this, he is an accomplished screenwriter and has even found himself in front of the camera, winning a prestigious Golden Horse award in both of these roles. He has built his career on hesui pian, commercial blockbusters known as “New Year’s comedies” because they premiere around Chinese New Year.

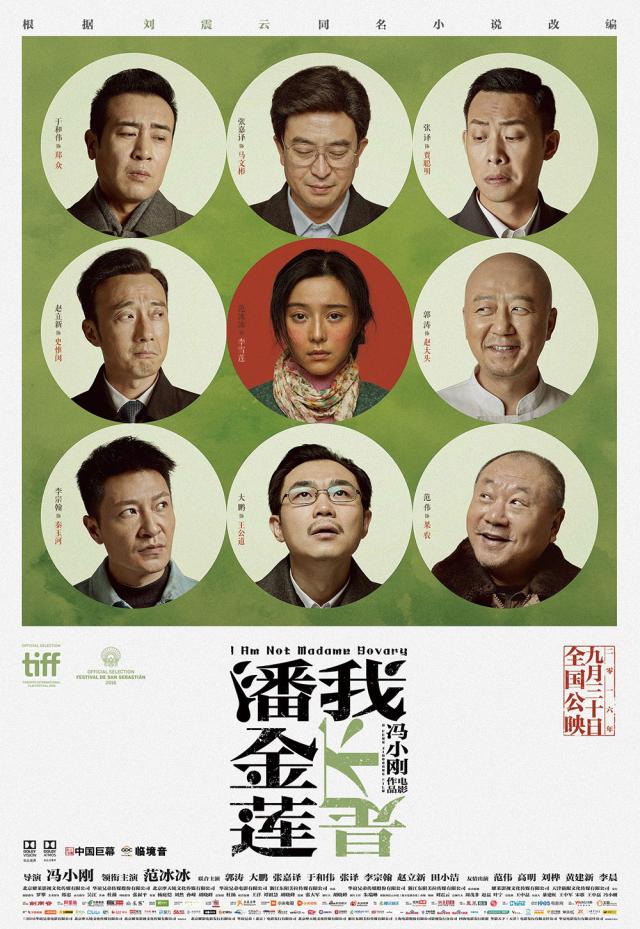

His latest movie, I Am Not Madame Bovary, stars Chinese superstar Fan Bingbing and was written by renowned author Liu Zhenyun, who adapted the screenplay from his 2012 novel of the same name. The film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September.

This film has been regarded by critics as Feng’s directorial return to his artistic ideals after years marked by numerous compromises with investors. This time, he did not have to contend with the restraints and limitations that had frustrated him in the past. I Am Not Madame Bovary is a politically critical and technically bold movie that showcases a director who is unwavering in his tone and artistic choices. This comes through most obviously in his decision to present nearly the entire two-hour film with a circular aspect ratio, meaning the audience mainly views the movie through a single, telescopic lens. Despite encountering opposition on this point from much of his crew, he insisted on the unique film style, even if it meant presenting viewers with a less accessible work.

Feng said he is done with holding back: “In my earlier days I had many concerns and made many compromises, but now I don’t want to have any regrets.”

Singular Lens

A satirical comedy, I Am Not Madame Bovary follows peasant woman Li Xuelian, played by Fan Bingbing, on a 20-year-long odyssey to reclaim her reputation. The movie opens with Li and her husband getting a “fake” divorce in order to take advantage of a real estate policy that favors single buyers. They plan to purchase an apartment while divorced, then remarry immediately after. But to Li’s surprise, her husband reneges on their deal, marries another woman and moves into their new apartment with his new wife. Li files a suit to annul their divorce out of anger; she plans to reestablish their marriage only to divorce him again, but on her terms. The court throws her suit out.

After her ex-husband further defames her by calling her a slut in public and claiming their divorce was genuine, Li becomes dead-set on winning her case in court as a means to get revenge and to recover her reputation. When one court denies her, she simply moves up the legal chain of command. She journeys from her small town to bigger and bigger cities until she eventually reaches the country’s capital. Over the course of two decades, Li’s savage determination takes down several members of the bureaucracy; newly unemployed officials drown in her wake. Nothing can stop her from pursuing what she believes to be right and just.

Initially, novelist and screenwriter Liu Zhenyun did not think it wise to adapt his book into a film. Because of the story’s two-decade-long time span, complicated plot structure and rich metaphors, he thought it would be extremely difficult to adapt to the screen.

His novel’s unusual structure would just made things more complex, he thought. The “prologue” makes up most of the book, while the main body is only a few thousand words. “Such a structure is rare but acceptable for a novel,” Liu said. “But it poses a huge challenge for a filmmaker who needs to edit the content for the filming process.”

Feng Xiaogang and Liu are old friends. They had previously collaborated on three other projects: the TV show Chicken Feathers On the Ground (1995) and the movies Cell Phone (2003) and Back to 1942 (2012). According to Liu, one of Feng’s core artistic principles is that his films must embody his own particular perspective. For instance, his movie Back to 1942 depicted the deadly famine that plagued Henan Province and killed three million Chinese during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Most directors would adopt a melancholic tone to deal with such a heavy subject, but Feng chose to tell the story through a compassionate but humorous lens.

“[Feng] Xiaogang has a very particular understanding of the relationship between film and life, and also of that between film and literature,” Liu told NewsChina. “His perspective is quite distinct from that of other directors. Usually a film requires… a well-woven, detailed plot, but Xiaogang cares more about the elements behind a story.”

Although the novel I Am Not Madame Bovary didn’t lend itself to adaptation, Feng was deeply touched by the bitter tale and became determined to capture it on film. “It is an authentic Chinese story,” he said. “It could only have happened in China; it could not have taken place in a Western country, or in North Korea. It grows out of the land under our feet.”

The director, who has loved the arts since boyhood and worked as a stage designer earlier in his career, was single-minded in his quest to give I Am Not Madame Bovary a unique aesthetic. To realize his vision, he changed the novel’s original setting, forgoing the relatively barren landscapes of northern China for Wuyuan, a county in the southern province of Jiangxi that is well known for its natural beauty and cultural heritage sites.

In Wuyuan, his camera could focus on ancient stone bridges, flagstone walkways brushed with hints of emerald moss and a gray drizzle dotting an engraved brick window.

But what made his movie’s visual choices singular was not the location, but the round frame through which it was filmed. The resultant circular image is reminiscent of the small, round paintings that emerged during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279). His audacious decision astonished the crew. Many of his crew members voiced opposition to this choice throughout the filming process, with the notable exception of Feng’s cinematographer.

“No one had ever done this before,” screenwriter Liu Zhenyun told NewsChina, giving his reasons for doubting the technique. “The round shape greatly limits the realization of the film’s visual effects.” Liu had openly voiced his disapproval to Feng twice. He even asked a mutual friend, renowned actor Zhang Guoli, to try to convince Feng to give up on this concept.

For his part, Feng tried to sway skeptical producers and crew members by explaining that this rounded lens recreates the visually poetic effect seen in ancient Chinese paintings. He said the peculiar style would distance viewers from the characters and remind them of their respective roles; the audience members are the observers, and the characters are the ones being observed. But no matter what Feng told his team, Liu Zhenyun, Zhang Guoli and producer Wang Zhonglei remained unconvinced.

Feng eventually lost his patience and said, “I’m done trying to convince you of this. This is the way we’re going to film it.” He later recalled: “I told [the producers] that if you don’t want to invest in my film, I will fund it myself, but I will shoot it with a round frame!”

Feng said his vision and his stubbornness in executing it showed the public that his “youthful heart” has not slowed with age. In fact, he has frequently told the press that he doesn’t feel old or middle-aged. “Even now, I always think I am still a child, full of whimsical ideas,” he said.

In the 1990s, well before Feng became China’s most successful mainstream comedy director, he was drawn to much darker subjects. To create the films for which he felt passionate, the ambitious director co-founded a film production company, Good Dream Corporation, with his friend Wang Shuo, a famous Beijing-born writer. After producing a series of dramatic films and TV series, such as Farewell My Love (1994), Ground Covered with Chicken Feathers (1995) and Elegy for Love (1995), Feng was forced to wake up from his “good dream,” as fewer and fewer investors showed interest in footing the bill for his somber films.

His company soon went bankrupt. Within a year of this setback, he began gravitating toward a different genre. In 1997, Feng, infamous for directing box office flops, debuted his first blockbuster: The Dream Factory. The movie tells the story of four friends starting a company in Beijing that specializes in making clients’ dreams come true. It is widely considered one of China’s first New Year’s comedies, a genre through which Feng achieved incredible success, even when faced with competition from Hollywood for domestic audiences. His movies drew wave after wave of Chinese viewers back to homegrown cinema.

But according to Feng, his commercial success often came at the price of his artistic integrity. Now, Feng is done compromising. That is why when it came to I Am Not Madame Bovary’s round frame, Feng willfully stuck to his controversial opinion and refused to budge. “Why did I insist on this?” he said. “Because I was terribly afraid that when I get older, I would regret not trying it.” Feng freely admitted he didn’t know how moviegoers would react to the limited, circular view. But he no longer wanted to have to sacrifice his creative desires for the sake of mainstream acceptability. “I don’t want to have regrets anymore,” he said.

In the end, Feng won his team members over. After watching the film’s final cut, screenwriter Liu Zhenyun ended up approving of Feng’s visual concept. “I suddenly understood him,” Liu said. “The round frame, like a telescope, has the effect of magnifying certain details. It helps reflect deeper, subtler details of life that are neglected in other movies.”

‘Weighty’ Comedy Feng once used the phrase “the weightiness of lightweight comedy” to describe a popular TV series he created back in 1992 called Stories From the Editorial Board. The two seemingly contradictory concepts, “weightiness” and “lightweight comedy,” can also be ascribed to the primary pursuit of Feng’s films.

Feng has long had a reputation as a director who knows how to please his audience. He has prided himself on staying largely tuned in to Chinese consumers’ fast-changing tastes. He knows how to make his viewers laugh, and how to weave a touch of bitterness into humorous storylines so that they are not only entertained, but also moved.

“I want to demonstrate a particular Chinese sense of humor; this sense of humor can only be grown and developed on our own land,” said Feng. In the novel Back to 1942, which Feng later adapted into a feature film, author Liu Zhenyun coined the phrase “the sooner you die, the sooner you’re relieved” to describe the average Chinese person’s attitude towards death. In Feng’s eyes, this wording contains a dark sense of humor. “It describes a way to comfort yourself when you are desperate and suffering,” he said. “I think it is a distinctly Chinese sense of humor. This is also the case in I Am Not Madame Bovary.”

Feng and Liu both define their most recent film as a comedy, but add that it’s “a weighty one.” The dark humor in I Am Not Madame Bovary “uses absurdity to confront life’s absurdity,” according to Feng. To Liu, his storyline comments directly on modern Chinese society and politics, “however it is not a political novel, nor is it a feminist novel.” Instead, it’s meant to explore the lower reaches of black humor and take on the ridiculousness of life.

As with his previous works, Feng did not inject humor in this film through slapstick comedy or ludicrous situations. Instead, I Am Not Madame Bovary has a much darker, satirical undertone, with plenty of witty lines and comical innuendo. Feng playfully stitches comedy into situations that audiences might otherwise find absurd or depressing.

The acclaimed novelist and dramatist Lao She once wrote: “The most tragic play I want to write is the one filled with barefaced laughter.” Feng’s brand of comedy is almost perfectly the opposite: beneath the wildest laughter and craziest twists lies a despondent sigh.

Shrewd Observer As a filmmaker, Feng attaches great importance to the storyline and its themes, keeping high-tech visual and technical elements to a minimum.

“I prefer stories that talk about people; their emotions and their hearts,” Feng said. “Many people have asked me to try making a 3D fantasy film. Could I do it? Of course I could do it. But I wouldn’t like it. That kind of stuff does not attract me at all. I never buy tickets to sci-fi films. I just feel that they have nothing to do with my life.”

He is seen as one of the few Chinese directors that can successfully walk the line between harnessing commercialism and being critical of it. He shows a peculiar interest in current social phenomena and can astutely capture the changing, below-the-surface problems that society has faced in recent years. This is most evident in Feng’s brand of comedy.

In his earlier comedies, such as The Dream Factory (1997) and Be There or Be Square (1998), he focuses on the widening gap between reality and people’s ambitions and dreams following China’s period of Reform and Opening-up. In Big Shot’s Funeral (2001), Feng explores how advertisements invade modern life. In Cell Phone (2003), which also starred Fan Bingbing, Feng depicts a world in which cellphones become more and more dangerous, eventually turning into explosives that destroy lives. His project the following year, A World Without Thieves (2004), revolved around modern China’s much-documented crisis of trust.

“I regard myself as a member of the common people,” Feng told NewsChina. “I see things from the perspective of the public, and the stance I take is no different than that of an ordinary person. Many people may have their own opinions towards some social issues but remain reticent. In my films, I am just expressing what they want to say.”

In I Am Not Madame Bovary, Feng deals with the conflict between morality and the law, which came to the fore as rural China gradually shifted from being a community governed by local values and traditions to a modern society governed by law.

Sometimes what people view as morally right is at odds with legal justice. The film’s protagonist, Li Xuelian, is a woman who has been wronged and cannot figure out why the law has chosen to protect a liar instead of a victim.

“Most people, including me, have been wronged in our lives, but the majority of us choose to let it go,” Feng told NewsChina. “Li Xuelian is a person who has been wronged but chooses to stand up and fight against it. Her boldness and insubordination will appeal to viewers who are accustomed to tolerating wrongdoing in their daily lives.”

“New social problems keep emerging as society develops. My films try to face these problems. Once a film forms a certain connection with viewers and society as a whole, more people will feel emotionally drawn to it.”

Old Version

Old Version